November 2009 Vol. 236 No. 11

Features

Monopsnimby: An Ambivalent Florida Faces Its Energy Future

Author’s Note: “Monopsnimby” is a compound noun from the combining of “monopsony” and “NIMBY” or “Not in My Back Yard.” It is used here to describe an energy (or other) market controlled by a small number of major buyers and anyone else who bothers to get organized. (source: Pace)

State and federal energy policy formulation is, at its essence, the ongoing attempt to reconcile the usually irreconcilable in the face of a changing geopolitical, economic and social environment. There are three main drivers evident in the decades-long policy debate and currently advocated prescriptions for the “best” energy policy.

As shown in Figure 1, the relative weights given these three often-competing vectors determine policy outcomes both in institutional contexts (Congress, state public utility commissions) and public opinion as reflected in the millions of choices made daily on personal comfort, convenience and mobility vs. financial and social cost. The plausible net expressions of these three drivers form the foundation of the energy market scenarios Pace develops to help clients assess the current and future risks and opportunities they may face in pursuing both public and private objectives.

Figure 1: Conflicting And Complementary Goals Of National Energy Policies.

These forces can promulgate rapid – if not always wise – social change when they converge and social paralysis when they don’t, often at no small peril to the very citizenry who public officials and industry planners seek to protect and serve. The curious case of Florida’s natural gas and power industry is a poster child for political gridlock when enduring energy infrastructure challenges confront public ambivalence, political expediency and corporate obstinacy.

Florida: The Exceptional State

In terms of energy supply, infrastructure and planning, the State of Florida is a unique distillation of the debate over energy security, cost and environmental impact now being conducted by the nation (and the world) at large. Consider:

- Florida’s economic and social welfare is highly dependent on the continuous flow of electricity through its transmission grid.

- The continuous flow of electricity is highly dependent on the continuous flow of primary fuels to power generators. As we shall see below, natural gas is becoming the dominant fuel for power generation.

- Florida is essentially devoid of both onshore hydrocarbon resources and the underground geological structures suitable for storing oil and natural gas.

- Commercial tourism interests and a public priority of preserving what is left of the environmental health of Florida’s coastline have blocked all oil and natural gas industry efforts to open Florida’s offshore to hydrocarbon exploration and development. Therefore, all primary fuels are “imported” across state lines.

- Florida’s energy regulators and established electric utilities have generally concurred that coordinated government/industry planning is the most effective way to ensure reliability and control costs. Therefore, aspiring and potentially disruptive new market entrants into the state energy sector are generally unwelcome.

The broadly shared goal of cleaner air and water has led Florida down the path of easiest implementation via public oversight of the predominantly regulated power generators. The state has elected to pursue a medium-term strategy that may foreshadow the elected paths of other states seeking to meet interim federal carbon reduction targets:

- No new steam plants burning “dirty” fuels, defined as coal and residual fuel oil (RFO);

- Early retirement or conversion of the remaining dirty units; and

- Demand growth and replacement capacity provided by cleaner options.

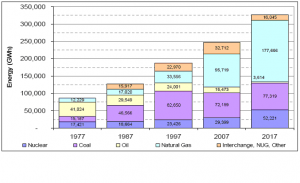

Although much is made of the anticipated 500 MW of new renewable generating capacity over the coming decade, about 70% of that growth comes from conventional steam boilers using biomass for fuel. As for the rest of the new generating capacity to accommodate growth and early retirements, the political push for lower carbon emissions has essentially eliminated coal and RFO as options. More nuclear capacity is coming, but lead times are long. Filling the breach is natural gas which is anticipated to hold a 54% market share among generator fuels by 2017 (Figure 2). Over 80% of the planned total new capacity is slated to be natural gas-fired. After tripling between 1997 and 2007, the market share for natural gas-fired power supply in 2017 will roughly equal the entire state power output in 1997.

Figure 2: Florida Power Generation Fuel Mix, 1977-2017 (Source: Florida Public Service Commission, Dec. 2008.)

This rapid and ongoing transition from an electric grid primarily powered by steam turbines fired by RFO and coal, with natural gas playing a supporting role, to the anticipated grid of 2017, for which system reliability and power costs will be tightly linked to the vagaries of natural gas supplies and market price, creates a critical challenge for system planners and regulators.

The Problem

A glance at Florida’s natural gas supply infrastructure reveals the problem (Figure 3). Florida’s “imports” of coal and fuel oil by rail, truck and barge are backstopped by in-state inventories in coal piles and tank farms that dot the Florida landscape and shoreline. With alternative delivery mechanisms and ample local supplies, any interruptions in fuel deliveries can be accommodated.

By contrast, lacking any in-state storage or alternate delivery mechanisms, the emerging Florida natural gas-fired grid is entirely reliant on the continuous availability and current cost of flowing natural gas supplies from the central and western Gulf Coast via two slender main straws: Florida Gas Transmission by land and Gulfstream Pipeline by sea. Additionally, Cypress Pipeline was constructed in 2007 from the Elba Island LNG terminal in Savannah, GA to Jacksonville. With a capacity of 336 MMcf/d, or about 10 percent of the Gulf Coast mainlines, Cypress provides Florida utilities with access to the only natural gas supply not sourced from the Gulf Coast.

To meet rapidly increasing natural gas demand for power generation fuel, both Gulfstream and FGT are expanding capacity. In addition, Florida Power & Light (FPL), the state’s largest utility, is seeking to build a proprietary intrastate pipeline system, connected by another long straw that basically parallels FGT, to serve its new natural gas-fired power plants. The operational and commercial risks of this situation are familiar to most readers of Pipeline & Gas Journal.

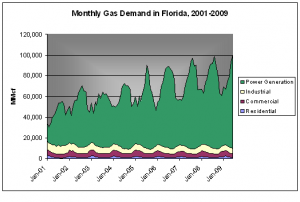

Meeting the peak requirements of a major natural gas demand node like the Florida peninsula, with its daily and seasonal load volatility (Figure 4), solely through long-haul pipeline capacity is expensive, inefficient and susceptible to major system failures. Pipeline system congestion during peak demand periods, with no alternate supplies, guarantees that periods of heavy power demand will be fueled at the margin by very scarce and expensive local spot natural gas. Any major disruption of pipeline deliveries in the supply area to the west, such as what occurred in the hurricanes of 2005, would overwhelm electrical grid managers operating under 2017 constraints. For both security and economic reasons, the state needs available surge capacity closer to home like every other major natural gas market in the U.S. and Canada.

This problem has not been overlooked by natural gas suppliers and Florida utility managers and regulators, but neither has it been solved. Back in 2001, Enron – then a 50 percent owner of FGT – proposed the first of a series of LNG import schemes to provide Florida markets with both a new fuel delivery alternative and a means of storing natural gas in-state to meet peaking requirements, avoid short-term natural gas price spikes and reduce supply interruption risks. LNG vaporizers are relatively cheap and, when operated in parallel, can quickly augment or replenish inadequate pipeline deliveries.

In a region lacking the necessary geology for underground natural gas storage, nearby LNG supplies with substantial dispatch capacity appear to be the best way to improve fuel supply security and reduce commodity price spikes during periods of peak demand. LNG, a global commodity, is also well-suited for Florida natural gas demand patterns, as it is in high demand during the winter months of the Northern Hemisphere, with availability high and prices low during the summer months when Florida needs the most fuel supply.(1)

Figure 4: Summer Power Generation Drives Florida Natural Gas Demand. (Source: U.S.D.O.E. Energy Information Administration)

Enron, of course, is no longer with us, but there has been no shortage of project successors and competitors offering similar services. Such companies as El Paso, AES and Tractebel (now GDF Suez) have advanced LNG import projects over the past decade designed and redesigned to meet the growing list of objections to such facilities from local citizens groups, environmental advocates and state and local government. As these projects evolved, FPL joined a consolidated project with El Paso and Suez to build an import terminal in the nearby Bahamas and dispatch the re-gasified LNG into Florida’s natural gas transmission network via a pipeline that was to come ashore in Palm Beach County, but dropped out in the face of rising commodity cost estimates and local opposition.

The AES proposal was to put the LNG terminal on a nearby manmade island and pipe the natural gas ashore. It too faced continuing opposition, and finally was killed by FGT, a threatened competitor for the Florida natural gas market, by revising its natural gas quality and composition specifications rendering AES’s LNG off-spec and out of luck.

GDF Suez persisted, changing its proposal to a tethered offshore mooring system and pipeline located off the Florida coast near Fort Lauderdale, and pipe re-gasified LNG directly from a tethered LNG tanker with topside regas facilities. After receiving all required permits, the proposal was finally vetoed earlier this year by Florida Gov. Charlie Crist in the face of strenuous and vocal local opposition.

The last surviving LNG import proposal, from Norwegian shipping company Hoëgh LNG, calls for a system similar to the GDF Suez proposal off the west coast of the Florida Peninsula where, once again, local government and public opposition is fierce.

Given Florida’s supply security and peak demand concerns, these LNG tanker mooring and dispatch proposals, designed to deflect NIMBY arguments about “saving our coastlines,” suffer from one defect: a very expensive LNG tanker must be tied into the delivery system for dispatch of any incremental natural gas supply: no ship, no natural gas.

Without local natural gas or LNG storage, Florida must bear the risk of abrupt supply curtailments and the cost of supporting long-haul pipelines designed to meet peak-day requirements. To address this concern, a small start-up company, Floridian Gas Storage, promoted an LNG storage project designed to avoid the many and varied objections to LNG imports by ship or short-haul pipeline.

The project developers propose an operating scheme common to many existing market-area facilities operated by utilities and pipeline suppliers: manufacture LNG on-site during off-peak periods when commodity prices are low and pipeline transportation is readily available, and dispatch vaporized LNG when operationally required or commercially attractive to plant capacity holders.

But, after all necessary government permits to construct the plant were secured and local concerns had been addressed, FPL announced that it had no need for supplemental natural gas deliverability given its other plans, and the project remains on hold. Albeit small, this would have been one of the relatively easy steps taken in providing supply security to Florida. Apparently, the Florida Energy Club does not welcome new members. Florida’s citizens will bear the costs and risks of this insularity.

The Cure

All these years of resistance to new natural gas supplies and storage could be reversed, and the state public interest served, if Florida politicians and regulators would resist the monopsnimby that has paralyzed industry efforts to improve the safety, health and economic welfare for all of Florida’s citizenry, but this will take political courage. Those who believe that burning fossil fuels, no matter how environmentally benign, is worse than not burning fossil fuels under any circumstances cannot be appeased.

Neighbors of any proposed in-state facility will opine that they’d rather see it located elsewhere. But state government must promote the general public good, not accede to personal preferences, unreasonable fears of remote or hypothetical dangers and narrow commercial interests. Florida utilities cannot afford to be complacent about the situation either. The Florida Public Service Commission is on record with its concerns about the precarious and increasingly critical natural gas situation, noting:

- “As the state continues to construct new natural gas-fired generation, natural gas storage and supply becomes increasingly significant in ensuring the reliability of the state’s electrical system. Multiple supply options and sufficient storage are critical to maintain the integrity of Florida’s electric system…. Utilities should continue to evaluate diversity within a fuel type, such as liquefied natural gas (LNG) and natural gas storage, as options to traditional sources and delivery methods for natural gas.”(2)

But wishing will not make it so, at least under the current rules of the game. If the state’s politicians and administrators can’t be convinced that the common good must take precedence over narrowly construed public and corporate self-interest, then they will have to suffer the eventual wrath of the majority of Florida’s voters left to live with the overpriced and uncertain electric service that will be left in monopsnimby’s wake. Contact: Mary.Knott@PaceGlobal.com.

References

1. Some hypothetical calculations of the economic and operating benefits of in-state LNG storage can be found at http://www.floridiannatural gasstorage.com/Presentations.html.

2. Florida Public Service Commission, Review of 2008 Ten-Year Site Plans for Florida’s Electric Utilities, December 2008, p.4.

Comments