April 2012, Vol. 239 No. 4

Features

LNG Exports: The Newest Economic Engine, Or A Fad That Will Pass?

At the end of 2011, the shale boom continued to spawn new-found expectations for U.S. oil and natural gas resources that contain large opportunities for the pipeline and other infrastructure sectors that are quietly riding the production upswing. Resulting low domestic gas prices relative to other global markets have sparked a scramble for export licenses to ship liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Europe and Asia.

The roughly decade-old strategy fostered by declining reserves in Canada and the United States that sparked a building boom for LNG import facilities on both coasts and the Gulf of Mexico (GOM) has been turned upside down. As a result, the infrastructure firms are gearing up for a new building boom to support exports.

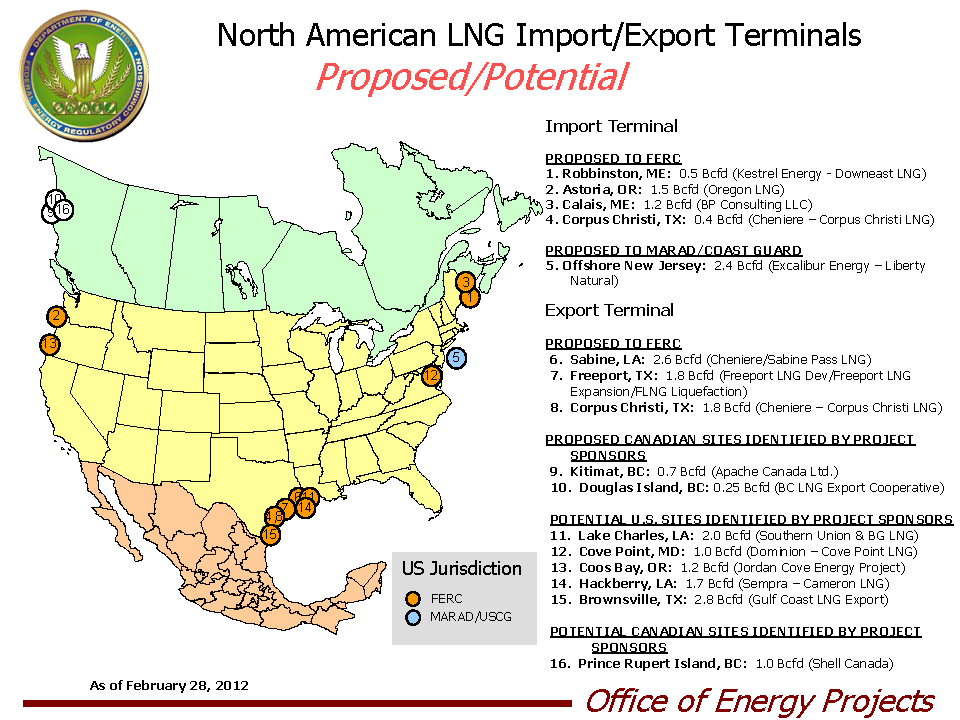

How and where it rolls out is yet to be determined, and may take several years to be sorted out, but in early 2012 it looks like all major coastal regions could have serious export projects and related facilities in the preconstruction stage. The activity should include Alaska and the U.S.-Canadian West Coast, which observers like the consultants at Canadian-based Ziff Energy Group think will be the leading locations for exporting gas.

In December, Ziff published a report, “North American LNG Exports,” identifying 10 proposed export sites – one on the East Coast, four in the GOM, and five on the U.S./Canada West Coast. It concludes that continued wide differences between U.S. gas prices and the rest of the world will make U.S. LNG exports inevitable.

At year-end, a Congressional Research Service report estimated that total LNG export proposals cumulatively would reach 12.5% of the current U.S. annual natural gas production in 2011. The report noted that pipeline exports, which accounted for 94% of the nation’s gas exports in 2010, were also expected to rise.

Surprisingly, various industry players with interests in future exports all talk fairly bullishly about the economic and technical logistics needed to build multibillion-dollar liquefaction facilities and related infrastructure, such as transmission pipelines and various gathering pipeline systems. Most of the time-consuming part of the export development involves regulatory and political hurdles, they say.

Energy consultants at Wood Mackenzie (Woodmac) assume it will take 10 years to get a North Slope gas-driven LNG export project going out of the Port of Valdez on the east side of the Kenai Peninsula in Alaska. Others think two or three years could be shaved off of that, but the key finding in a Woodmac report in mid-2011 was that Alaskan LNG exports potentially could generate up to $419 billion during the 30-year life of a project for the U.S. economy, particularly in Alaska.

Competing interests for a pipeline through Canada to the United States, which has been a focus of many pipeline and infrastructure companies, particularly Calgary-based TransCanada Corp., argue an export option does not meet regulatory and other economic hurdles.

Four years ago a consultant’s report to Alaskan government officials said an export project would “likely confront significant, expensive, and time-consuming barriers” based on a myriad of requirements for applications to, and approvals by, a host of federal agencies, not to mention U.S. State Department and national security concerns. By contrast, the report found a pipeline-only approach through Canada confronts none those problems, according to the authors, Greenberg Traurig LLP, writing back in 2008.

That mindset has changed, according to Bill Walker, an Anchorage-based attorney and former mayor of Valdez who represents the Alaska Gasline Port Authority (AGPA) for which Woodmac produced its report last July, “Alaskan LNG Exports Competitiveness Study.”

AGPA, which is about 12 years old, is what Walker calls “picking up the torch” from Yukon Pacific Corp. after it relinquished a federal right-of-way grant last fall that it had held for nearly two decades. “We’re called the all-Alaska line to Valdez and then liquefaction for export.”

Walker says Wood MacKenzie looked at the AGPA proposal and showed that its costs out of Valdez could get gas to Japan for about $8.50/Mcf while Kitimat is $11.30/Mcf.

“They compared us to a lot of Australian and lower 48 projects. The big difference is our cost of gathering gas on the North Slope is about 26 cents/Mcf because it is all associated gas. That is where we really have an advantage.”

Separately at the end of 2011, ConocoPhillips secured a new gas supply in the Cook Inlet from Australia-based Buccaneer Energy Ltd. that allowed it to begin exporting LNG to Japan again, at least until the Kenai LNG plant’s export license expires in 2013. Earlier in 2011, ConocoPhillips was preparing to mothball its Alaskan LNG facility, which has been exporting gas to Japan since 1969.

“There has always been the prospect of an LNG export facility located at Valdez, but until a pipeline from the North Slope gets sorted out there is little movement on that idea,” says Bob Braddock, project manager for the Jordan Cove LNG project along the south-central coast of Oregon at Coos Bay. Braddock’s FERC-certified LNG terminal and connecting 230-mile transmission pipeline, Pacific Connector, were changed in 2011 to a combination import-export project.

Canadian gas infrastructure giant TransCanada is tied to proposals to bring North Slope supplies to the United States and Canada through an elongated pipeline system that has had various iterations for literally decades. However, the Calgary-based North American operator is keeping a close eye on LNG export developments, according to Terry Cunha, a Calgary-based TransCanada spokesperson.

“Our primary interest is providing natural gas pipeline infrastructure to support competitive LNG developments,” Cunha says. “We are most keenly interested – and we believe most competitive – in LNG projects that are located in areas where our existing pipeline infrastructure can be utilized, such as the potential Kitimat [British Columbia] projects on the West Coast, for example.”

Cunha says TransCanada expects to provide competitive natural gas pipeline transportation services for LNG terminals. In 2011, the Canadian pipeline and storage company had not been asked to participate in any liquefaction facility development, he says.

“We could not totally rule out participating in a liquefaction plant at this point, but I would say that in order for us to participate there would need to be significant evidence that we could add real value to the project outside of the pipeline portion.”

While pipeline and infrastructure officials are not convinced the export push can bear fruit because of infrastructure and regulatory challenges that weaken the economics of such projects, many of the current LNG and pipeline/storage operators see infrastructure as the least of the hurdles. They are particularly enthusiastic about brownfield sites where existing import terminals now operate.

They expect the places where abundant infrastructure in terms of transmission pipelines, gathering systems, storage and marine facilities already exists to be the prime candidates for export projects.

Ziff Energy’s Bill Gwozd thinks the new sites may be as much as 70% more costly to develop, but he believes the location of new export terminals on the U.S. and Canadian West Coast have superior economics because of their proximity to the highest-priced global LNG markets, all found in Asia. GOM export facilities will be built, but they will probably stay largely under-used as the current U.S. import terminals are, Gwozd says.

In a career spanning nearly 40 years in the gas business worldwide, recently retired Sempra Energy LNG CEO Darcel Hulse has seen booms and busts and two different cycles of LNG-receiving terminal development around the U.S. coastal areas, but never has the conventional wisdom been upended as quickly as the last few years of revolution in shale plays.

“Shale formations and the technology to get at the gas changed the picture dramatically,” says Hulse who retired the end of 2011. “So now we see the three major [LNG] markets globally – Europe, Asia and the U.S. – just really disconnected in terms of prices,” he cautions, calling it a “unique market situation” unlike any other major commodity in the world. He also doesn’t make any long-range predictions on how long this trend will last.

Late last year, a report by Deloitte for would-be LNG exporter BG Group concluded that domestic natural gas prices would increase only by pennies as a result of a newly developed export market for U.S. supplies. The biggest impact would likely be in the GOM states, the report projected.

Ziff Energy’s pricing model estimates that for every 1 Bcf/d of exports, domestic prices would increase 22-23 cents/Mcf, says Gwozd, adding that new gas-fired power generation will have a bigger impact on domestic prices.

For the past two years, low gas prices obviously have supported the call for exports out of the United States, particularly with existing (brownfield) projects. These are the existing facilities where people like Hulse, who know firsthand, say adding a liquefaction train to a regasification facility is relatively easy.

“The liquefaction facility is nothing more than a giant refrigeration cycle,” Hulse says. “It is very large equipment, driven by gas turbines or electric motors depending on the power supply available. But the heart of this facility is just compressors and heat exchangers. Those are all offsite items produced in shops and factories capable of building all of that.”

The components are easily shipped, mounted on foundations and then interconnected at the site. Hulse thinks the GOM is today’s oil/gas global center for technology and workforce expertise to build these facilities.

“Those facilities, such as Sempra’s Cameron site in Louisiana, basically have the marine docking and storage tanks already developed. That is particularly attractive,” says the man who led the development of Cameron and Sempra’s LNG-receiving terminal along the Pacific Coast in North Baja California, Mexico.

In most cases, terminal operators like Sempra will look for a couple of things before they travel too far down the export road. One will be well-heeled, A-credit rated partners, and the second will be similarly strong shippers. In some cases, the partners and the shippers may be the same entities.

Transporting more than 75% of all the gas that moves in western Canada, TransCanada is viewed as being in an extremely good position to be able to provide access to supply and transmission services to the liquefaction facilities being proposed in British Columbia. It has firm contracts to move most of the emerging gas production from the Horn River, Montney and Cordova plays, Cunha says.

TransCanada also operates Gas Transmission Northwest (GTN) between Canada and the California border, and runs the U.S. part of the North Baja Pipeline connecting with Sempra’s Costa Azul facility with southwest shippers at the California-Arizona border and the LNG facility near Ensenada, Mexico.

“We are continuing to expand our western Canadian gas gathering and transmission system to ensure that gas production from the entire basin is connected to markets,” says Cunha, adding that during the past five years, TransCanada has spent about $2 billion on expansions and extensions, and he forecasts that sort of growth to continue.

What he calls a “tolling methodology” used in the TransCanada system makes it possible for any western Canadian basin gas production to access any and all LNG supply lines, regardless of the production’s location, Cunha says.

If the West Coast project(s) move ahead, the cost of building adequate transmission pipeline capacity will depend on how much overall gas capacity is being exported, but in any event, connecting western Canada production areas to the British Columbia coast will be “multibillion-dollar” undertakings, Cunha says.

TransCanada stresses its historic infrastructure role, and downplays any possible leap into an equity position in one or more of the proposed export projects. Nevertheless, one of the newest proposals in Oregon – Jordan Cove – is strategically positioned for accessing the GTN pipeline, bringing both Canadian and U.S. Rockies supplies to the coastal plant’s connecting transmission line.

“Our main interest continues to be supplying natural gas pipeline infrastructure for these export projects,” Cunha says.

Jordan Cove project backers announced last fall that they would seek to make their proposed LNG facility and its 1.2 Bcf/d connecting transmission pipeline a dual export-import project, which means the pipeline flow would have to be reversible.

“Yes, we made the decision to pursue the development of a dual-use LNG facility based upon the strong indications of interest from prospective terminal capacity holders,” Jordan Cove’s Braddock told news media at the time. “While we have not reached any firm agreements for the terminal capacity, we feel strongly these commitments can be reached within the next few months [first quarter 2012].”

In November, Braddock said Jordan Cove was now “cautiously proceeding” with “the critical steps necessary to secure all of the approvals and consents” needed to construct and operate Jordan Cove in dual-use configuration. He anticipated that to be a two-year process.

Like Jordan Cove, the related 234-mile, 36-inch Pacific Connector Pipeline Project has FERC approval, but it is working its way through various state and federal land-use and environmental permitting processes that will take at least another 12-15 months, according to Braddock. The switch to an export location won’t change much for the consortium pipeline, he says.

The former Sempra LNG leader, Hulse, would not comment on prospective West Coast projects in Canada or the United States, preferring to stick with his conviction about virgin sites having more costly unknowns than existing LNG receipt facilities. To Hulse, the economics are superior for the existing sites.

“All I would say is that when you have a brownfield in a key location, you have an economic advantage and you have taken a good portion of the risk out of the project,” he said in December in an extensive interview.

“You’ve already constructed a lot of the facilities that take a lot of manpower during construction, so for that part of the project the risk has been removed.” The engineering and logistics, aside from political/regulatory considerations, easily fall into place, according to Hulse.

What is really involved in developing an export capability?

“On the liquefaction side, you have much larger components, you order them in advance, you know the prices of the equipment, you install them and then in effect hook them up, so your man-hours to the total cost are much lower than if you were still building tanks and marine facilities,” Hulse says.

There are contractors in the U.S. that have built these overseas, but Hulse thinks probably the best place to build one of these facilities is in the Gulf of Mexico. “They are probably the standard in the global industry by which productivity is measured.”

He sees “potentially thousands of jobs” in the energy sector that could be created by an export movement. That includes thousands of construction jobs and many permanent jobs going forward.

“The economic pull for this kind of thing would be tremendous for this country,” Hulse says. “So when we take a look at all of this, there are some very compelling [national interest] reasons from the standpoint of GDP, balance-of-payments, jobs-creation and other reasons why these [LNG exports] would be very good projects for the economy and the future of the country.”

Like TransCanada and other infrastructure companies, Sempra sees its role as developing infrastructure with the backing of long-term contracts with highly creditworthy companies. “That is kind of the nature of our business. We will not put our shareholders at risk for large market flings,” Hulse says.

Sempra senior executives say they have received substantial interest in LNG exports from gas producers who are willing to take on the risk of signing export contracts, according to Hulse. The producers are “very interested in an export capability at Cameron and they are the people who could handle that added risk in seeking increased value for their gas. They’re like anybody else who produces and delivers a commodity.”

Sempra has submitted an export application to DOE for 12 million tons annually, which would be 1.7-1.8 Bcf/d equivalent. The GOM is a global center for technology and workforce expertise to build these facilities, according to Hulse and others.

For the gas industry, LNG exports appear to be a certain part of future U.S. developments. It is just a question of when and how extensive they will be. And Ziff Energy’s Gwozd would add another question, when and where they can become of long-term value to investors?

Richard Nemec is P&GJ’s West Coast Correspondent in Los Angeles. He can be reached at: rnemec@ca.rr.com.

Comments