November 2012, Vol. 239 No. 11

Features

Alaska Producers Envision LNG Export Mega Project

Alaska North Slope producers are considering building one of the world’s largest and most expensive liquefied natural gas projects, according to a letter the companies sent last month to Gov. Sean Parnell.

The exports primarily would target Asian markets.

The early concept envisions a project costing $45 billion to possibly more than $65 billion, with exports of 15-18 million metric tons of LNG annually, the equivalent of 2-2.4 Bcf/d of natural gas. The cost estimate includes a gas treatment plant, pipeline to tidewater, a liquefaction plant and 15-20 LNG tankers.

The Oct. 1 letter from executives of ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, BP and pipeline company TransCanada stressed that their project is in its early stages of planning. They estimated a decision on whether to actually build the project is at least three years away, and if they do build it, the first LNG wouldn’t flow before the early 2020s.

“We have narrowed the broad range of alternative development concepts and assessed major project components, including the gas pipeline, gas treatment to remove CO2 and other impurities [from the produced gas], natural gas liquefaction, LNG storage, and marine terminal facilities,” the letter says. “Individually, each of these components would represent a world-class project. Combined, they result in a mega-project of unprecedented scale and challenge: up to 1.7 million tons of steel, a peak construction workforce of up to 15,000, a permanent workforce of over 1,000 in Alaska, and an estimated total cost in today’s dollars of $45 to $65+ billion.”

The next steps include preliminary engineering, environmental data collection, assessing commercial viability and working with the Alaska state government to set long-term fiscal terms. “The facilities currently used for producing oil need to be available over the long-term for producing the associated gas for an LNG project. For these reasons, a healthy, long-term oil business, underpinned by a competitive fiscal framework and LNG project fiscal terms that also address AGIA issues, is required to monetize North Slope natural gas resources.” AGIA refers to the Alaska Gasline Inducement Act, the 2007 state law under which the project is being considered.

Alaska’s North Slope region holds an estimated 35 Tcf of proved natural gas reserves, most of it associated with the oil production that began in 1977. Some produced gas is used to power the more than two dozen oil fields there, but without a gas pipeline most is re-injected to help push more oil from the ground.

The letter to Parnell from Randy Broiles of ExxonMobil Production Co., Trond-Erik Johansen of ConocoPhillips Alaska Inc., John Minge of BP Exploration Alaska and Tony Palmer of TransCanada said the project concept today envisions an 800-mile, 42- to 48-inch pipeline that would carry 3-3.5 Bcf/d. Some of that gas would be consumed in Alaska and some would be used to run the liquefaction plant and pipeline compressor stations.

The letter says the companies have assessed 22 sites along the Southcentral Alaska coast for location of the LNG plant and tanker port. It did not indicate a preferred site. As conceived, the LNG plant would use three parallel processing lines — called trains — of 5-6 million metric tons each to superchill the pipeline gas to make it liquid for ease of transport.

“We will continue to keep you advised of our progress and stand committed to work with the state to responsibly develop its considerable resources,” the officials wrote.

Team Of 200 At Work

Already, Exxon Mobil, Conoco Phillips, BP, and TransCanada say they have a team of more than 200 people working on the Alaska LNG project. BP has the lead role on the commercial side, with Exxon the technical lead.

“There are always bumps in the road, and certainly no guarantees. There are no guarantees now,” Natural Resources Commissioner Dan Sullivan said. “But we’ve already traveled a good distance in a short amount of time since that state of the state, and our intent is to keep that pedal to the metal working with all key stakeholders and to try to realize this very significant opportunity.”

Sullivan said the state has a sense of urgency and is pushing for accelerated work. For instance, development of North Slope gas was held up for years by litigation over the huge, remote Point Thomson oil and gas field, operated by Exxon Mobil. Settlement of that dispute earlier this year included an incentive for a pipeline investment decision by mid-2016, which fits the new timetable, Sullivan said.

But that still puts off a decision on whether to build the pipeline for four years. Construction would be five or six years from now, under the timeline. And in the meantime, competing LNG projects around the world are moving ahead.

The energy companies are calling for “competitive and stable fiscal terms” from the state. Parnell had said that if the companies met his benchmarks, then the state could look at gas taxes next year. He has failed in his attempts this year and last to get an oil tax cut passed.

The world’s largest LNG plants — in Australia and Qatar — can make 15-16 million metric tons of product annually. A plant planned for construction in Louisiana will be a little larger. The Gorgon plant under development in Australia is estimated to cost about $40 billion.

A recent LNG conference in Valdez was focused on the benefits and attractions of building an export terminal at the port city for shipping orth Slope gas to Asia. But several speakers acknowledged the problems in getting anything built anywhere in Alaska to move natural gas to market.

Divisive Communities

“There is a great division among communities,” Rep. Don Young (D-AK) told the audience via video link from his congressional office in Washington, DC. Alaska municipalities need to get together on a single LNG project rather than battle for the role of host city, Young said.

Alaskans need to figure out how to get it done without dividing the state, he told the 120-plus attendees at the Sept. 13-14 Alaska LNG Summit 2012 sponsored by the Alaska Gasline Port Authority. The authority, comprised of the city of Valdez and the Fairbanks North Star Borough, has been pushing since 1999 for a large-volume North Slope gas pipeline leading to an LNG export terminal in Valdez and against other proposed Alaska gas projects.

But building a pipeline from the North Slope to Southcentral Alaska to feed an LNG plant on the Kenai Peninsula is worse than doing nothing, said Craig Richards, an Anchorage attorney who shares a practice with Alaska Gasline Port Authority general counsel Bill Walker.

This so-called bullet line, promoted by many Alaska legislators including Republican House Speaker Mike Chenault would prevent a bigger pipeline from getting built for a decade, Richards said. In addition to pushing for a bigger line to Valdez over the Kenai Peninsula, Richards is no fan of the major North Slope producers owning the pipeline and LNG terminal.

“Take control away from the producers” is the best option, Richards said, calling for the state to take the lead on a Valdez project. His partner, Walker, delivered the same message, arguing for the state to build and own the pipeline and liquefaction terminal. The Walker and Richards firm also serves as city attorney for Valdez.

No Easy Task

All of the conference speakers agreed that long-term gas sales contracts would be needed to finance the project, much like those Cheniere Energy obtained to underpin financing of its LNG export terminal planned for Sabine Pass, LA and scheduled to open in 2015.

Putting together an LNG export project is not easy, said Bob Gibb of Navigant Consulting’s energy practice, based in Austin, TX. In addition to massive capital costs, a project needs 20-year sales contracts with gas buyers and the developer has to deal with the significant risks of unpredictable market demand and intense competition from other LNG suppliers.

“Let’s take the game to the rest of the world and see if an opportunity at tidewater exists,” said Kurt Gibson, director of the Alaska Gas Pipeline Project Office and the only state official on the agenda at the two-day meeting.

“We’re competing in a global market,” Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) said. “No other single project is as important to Alaska’s economic future as a gas line, so it’s critical that the state and the producers move quickly to take advantage of the potentially limited window of opportunity to sell gas into the Asian market.”

And time is tight, said Radoslav Shipkoff, director of Greengate LLC, a Washington, DC-based adviser that specializes in project debt financing. “This window of opportunity is not going to last forever,” he said.

“The biggest impediment for Valdez to go forward is political,” said Octavio Simoes, president of Sempra LNG in San Diego, a longtime supporter of the Valdez project.

The state could continue with its current path under the Alaska Gasline Inducement Act, he said. That has TransCanada leading the state-subsidized effort. Or, as a “different structure,” Simoes said, the project could take place outside of the 2008 AGIA deal and, in its place, the state could “create a consortium of creditworthy Pacific Basin gas buyers to permit, finance, build and operate the facilities.” He advocated that whatever the state chooses, it would be best to find a way to bring all interested parties together.

Sempra in 2004 signed a non-binding development agreement with the port authority and contributed several million dollars to jointly consider and promote the Valdez LNG project. The company ended its relationship in 2005, blaming “protracted political wrestling within the state” among the reasons for its departure.

House Dems Seek Delay

The project puts the Obama administration’s role in exporting natural gas back in focus, as it would need to approve pacts with South Korea and Japan. A group of 20 House Democrats told the Energy Department Sept. 26 that it should complete an environmental review before approving LNG exports. In a letter to Energy Secretary Steven Chu, the lawmakers expressed concern about the amount of hydraulic fracturing that would be needed to meet demand for natural gas exports.

Led by Democratic Reps. Jared Polis of Colorado and Maurice Hinchey of New York, the lawmakers called on the department to conduct an environmental impact statement, as outlined under the National Environmental Policy Act, before approving exports. “We are concerned that exporting more LNG would lead to greater hydraulic fracturing … thus threatening the health of local residents and jobs,” the letter said.

Other lawmakers, however, have pushed the administration to expedite export approval. They say the opportunity to sell U.S. gas at higher prices abroad could be a financial boon that creates jobs and stabilizes the energy market. But others, mainly Democrats, have urged caution. They say LNG exports could raise electricity prices for consumers and manufacturers, on top of environmental concerns. The department is waiting for a report on the economic effects of exports before taking action on applications.

Oil Production At Risk

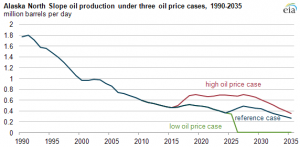

A new report released by the federal Energy Information Administration finds that projected Alaska North Slope oil production could be at risk beyond 2025 if oil prices drop sharply.

Oil production on the North Slope, which has been declining since 1988 when average annual production peaked at 2 million bpd, is transported to market through the TransAlaska Pipeline System (TAPS). Because TAPS needs to maintain throughput above a minimum threshold level to remain operational, its projected lifetime depends on continued investment in North Slope oil production that itself depends on future oil prices. In the Annual Energy Outlook 2012 low oil price case, North Slope production would cease and TAPS would be decommissioned, which could occur as early as 2026.

The 48-inch, 800-mile long TAPS crude oil pipeline transports North Slope crude oil south to the Valdez Marine Terminal, where the oil is then shipped by tankers to West Coast refineries. TAPS is currently the only means for transporting North Slope crude oil to refineries and the petroleum consumption markets they serve.

Low flow rates on crude oil pipelines can cause operational issues, particularly in the frigid Arctic. On June 15, 2011 the TAPS operator—Alyeska Pipeline Service Company—released the TAPS Low Flow Impact Study that identified the following problems that might occur as North Slope oil production progressively declines below 600,000 bpd, thereby resulting in declining TAPS throughput:

• Potential water dropout from the crude oil, which could cause pipeline corrosion

• Potential ice formation in the pipe if the oil temperature were to drop below freezing

• Potential wax precipitation and deposition

• Potential displacement of the buried pipeline due to soil freezing and thawing, as pipeline operating temperatures decline

Other potential operational issues at low flow rates include: sludge drop-out, reduced ability to remove wax, reduction in pipeline leak detection efficiency, pipeline shutdown and restart, and the running of pipeline pigs that both clean and check pipeline integrity.

The severity of potential TAPS operational problems is expected to increase as throughput declines; the onset of TAPS low flow problems could begin around 550,000 bpd, absent any mitigation. As the types and severity of problems multiplies, the investment required to mitigate those problems is expected to increase significantly. Because of the many and diverse operational problems expected to occur below 350,000 bpd, considerable investment might be required to keep the pipeline operational below this throughput level.

Analysis of Alaskan production in the Annual Energy Outlook 2012 (AEO2012) assumed that the North Slope oil fields would be shutdown, plugged, and abandoned and TAPS would be decommissioned, when two conditions were simultaneously satisfied: 1) TAPS throughput was at or below 350,000 bpd and 2) total North Slope oil production revenues were at or below $5 billion per year. These conditions are satisfied only in the AEO2012 low oil price case, when North Slope oil production is shutdown

Comments