April 2013, Vol. 240 No. 4

Features

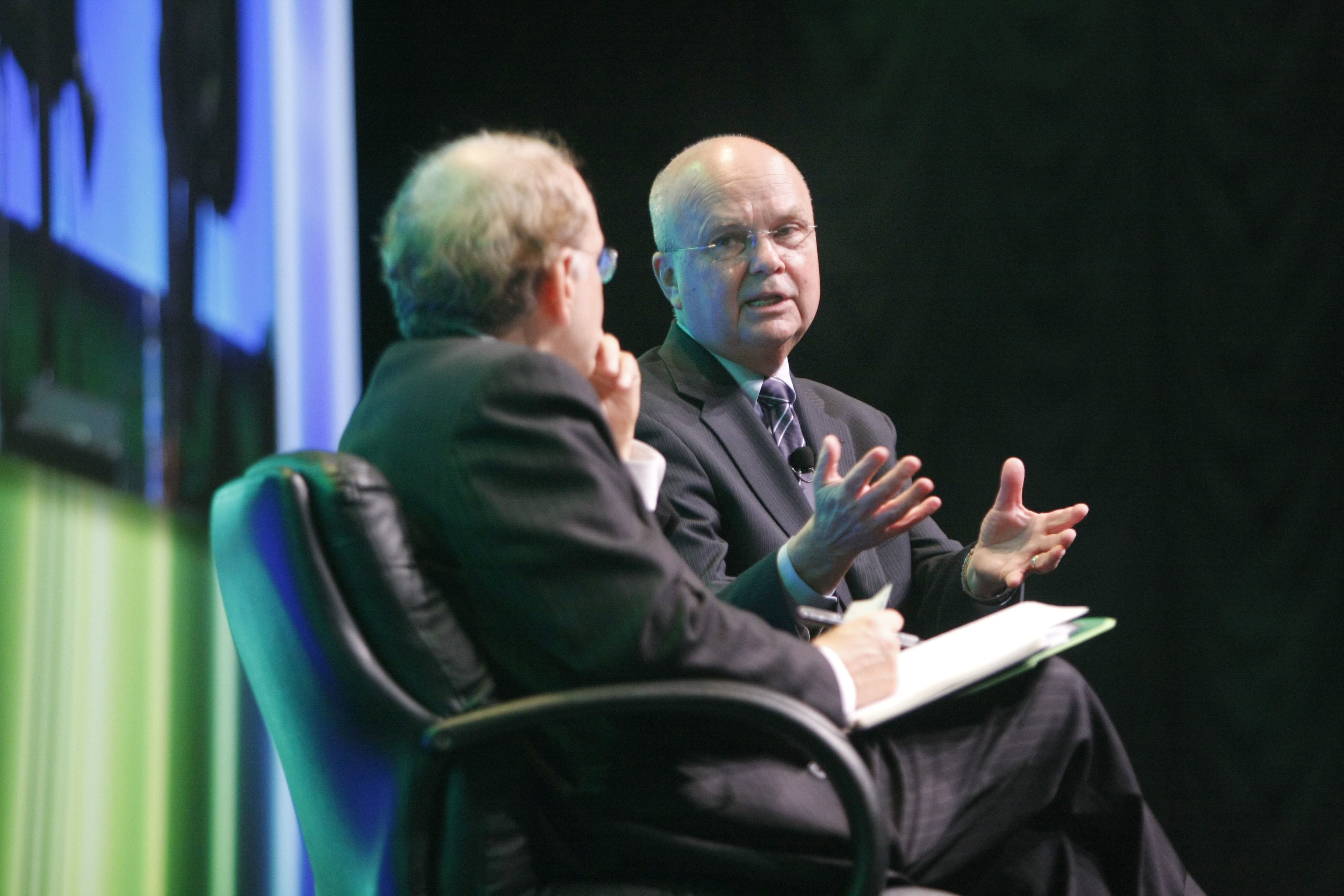

Not If But When: CERAWeek On Cybersecurity

Oil and gas companies need to change their perspective on cybersecurity initiatives from one of incident-based response to a holistic approach more analogous to counterintelligence to prevent espionage, said experts attending IHS CERAWeek 2013, March 4-8. A two-part strategy to decrease exposure and mitigate possible consequences was recommended for a realm where the consensus was that some degree of infiltration is nearly inevitable.

Meanwhile, in the March 12 Intelligence Community Worldwide Threat Assessment, an annual briefing to the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, the directors of the CIA, FBI, National Intelligence and other security organizations named cyber attacks the biggest threat to the United States.

Cybersecurity is becoming a focus across many business sectors, but the energy industry, including pipelines, has particular vulnerability. According to Gen. Michael Hayden, former head of the CIA and NSA, now consultant for the Chertoff Group, oil and gas companies make an attractive target. “Where they have to work, the kind of symbolism they bring into the equation, the need to rely on automation: with that, it seems to me they need to work very hard on their own defense.”

The silver lining is that the current hazard is primarily economic rather than violent. Although incidents are frequently referred to as “attacks,” Hayden points out, “That’s sloppy language.” It would be more accurate to call these events computer network exploitations: “Stealing your stuff. And that’s pretty much all that’s happening right now. We call it an attack in our public discourse, but technically we would never call it an attack. That’s espionage.”

The infiltration of Telvent’s systems in September 2012, for instance, involved both installation of malware and theft of files concerning its OASyS SCADA system, popular among pipeline companies.

Northrop Grumman’s vice president for Cyber Solutions, Ron Foudray, said that many incursions are not designed to deny or disrupt service, but are instead intelligence-gathering operations. “Many people are interested in how do you do hydraulic fracturing? Where is your next dig site? What are the things you’re investing money in?”

That’s remarkable, said Hayden, because uniquely in the realm of cyberwarfare, taking down a system or otherwise destroying it is among the easier things an adversary can accomplish.

“When you’re talking about destructive activity, reconnaissance comes first. You do that then you do the operation. In the physical domain, land, sea, and air, reconnaissance is an easier task than the actual fight.” With digital aggression, reconnaissance still has to come first, but it’s harder than completing an operation.

“It’s more difficult to penetrate a network where you’re not welcome, to live on it undetected for a long period of time, extract information from it while remaining undetected – it’s far more difficult to do that than it is to penetrate it and kick in the doors.”

If you find an unauthorized presence on your network, Hayden said, “in many cases, they have already demonstrated a capacity to do your network harm, though they appear not to have chosen to do so and instead are stealing your network blind.”

Therefore, he said, finding an intruder on a low-information SCADA network is extremely concerning.

Although digital battles are a classic example of asymmetric warfare, with clear advantages to the offense, few reported events have been of a destructive nature and none aimed at terrorist goals.

Hayden said the reasons behind that fact were unclear. “This is puzzling to me. This is a fairly defenseless domain; it’s pretty easy to be at least irritating and not overly hard to do some kind of damage. And yet I cannot find an example of Al-Qaida using the Internet for anything other than its own communication. They use it to communicate, to proselytize, to recruit, to train, to raise finances. They seem pretty adept at it, but I can’t find an example of Al-Qaida sponsoring a cyberattack.”

Not If But When

The exposure to some kind of security breach is extremely high, however, to the point that companies need to adjust their outlook from an “if this happens to me” to a “when this happens to me” mentality, said Shyam Sankar, director for Forward Deployed Engineering of Palantir Technologies.

Handling a digital incursion is an operational reality, not “a scary thing that one hopes one never has to deal with. It’s ‘How do I deal with this?’ just like ‘How do I deal with slips and falls?’, or someone quitting. In a real institution of any importance these things happen.”

Deputy Secretary of Energy Dan Poneman highlighted the futility of attempting to treat computer systems as a hard border. “You cannot defend the perimeter. It’s a Maginot Line.” That approach was likely to result in an “M&M problem: hard on the outside, soft on the inside” in which enemies would be able to achieve their goals easily once they accessed a system.

Sankar described a split in security philosophies between companies. “There’s one group that views this as a compliance problem, getting the right alert when something goes wrong. But the alerts are basically all noise. There’s a lot of false positives so that you don’t miss anything.”

The more sophisticated approach focuses on qualitative analysis. “What is the impact to my business? The question becomes one of a more operational nature: How do I mitigate these threats?” Sankar estimated that fewer than a quarter of oil and gas businesses approach the problem this way.

Isolated Assets, Connected Vulnerability

Many companies handling remote networks such as SCADA systems assume isolation provides protection, said Dennis Murphy, senior analyst for Cyberspace Operations for IHS, but there are still dangers. “The Achilles’ heel is the human being who picks up a thumb drive that has malware on it,” either intentionally or because the drive has been compromised. “That human in the system has to be addressed.”

IHS Director of Global Energy Services Michael Wynne noted that “automation requires tight observation.” Some viruses are slow-moving but hard to detect, and “pretty pervasive in things like SCADA. They will just sit there quietly and like a game of chess, they’ll take one move forward every time the opportunity presents itself, until they get where they want to go, which in this case is SCADA-based equipment.”

Another source of threats is unsecured transmission methods and blind spots on the means of communication. “Think of smart meters,” said Foudray, the Northrop Grumman expert. “Smart meters report back through cell towers. There’s vulnerability. Unless that’s an NSA Type 1 Suite A or Suite B encrypting device, it’s being exploited.”

Controlling Access, Controlling Consequences

A defense-in-depth approach, in which each layer of a network is considered and protected, was the practical solution of choice for most of the speakers. Moving focus from how to keep adversaries out to decreasing the consequences of any incursion was also emphasized repeatedly.

Jasvir Gill, CEO of AlertEnterprises, advocated considering physical security and location-based access as a layer of cyberdefense, particularly for unmanned assets. If an alert goes off for a remote substation, “It might seem like an attack but it could be just a squirrel. At 11 at night, do I send a guy with a gun, or a guy with a wrench?”

Cameras could help provide a “surgical response,” but situational awareness is key. If an employee is onsite, is it someone trying to catch up on work, or a disgruntled employee about to lose a job? “Find out what the problem is, put it in a broader context, and then you respond. If someone’s on the network, is the person physically there?” If not, it might be a sign of an attack.

Location- and logic-based access for allowing devices to connect to the system, rather than allowing access based on the particular device, could increase protection of less remote systems too, with examples such as mobile devices that can only access the network from the company’s offices and other authorized locations.

Hayden agreed with the approach. “When you try to [infiltrate a network] remotely, access is everything. Access is the most difficult issue. When you jump over the access problem with an internal actor, it doesn’t suggest as much sophistication.”

The ultimate solution is a system that can detect and respond to threats automatically. Poneman called it a “self-healing grid,” while Hayden described it as “organic, almost biological in its response to a foreign object.” But as of yet, this type of system is a goal, and not a reality.

With best practices in flux and risks running high, Palantir’s Sankar emphasized internal engagement with the issue. “You can’t deal with this problem simply by getting some kind of a black box and buying your way out of it, you actually have to invest your own intellectual capital. Only you can effectively protect yourself right now.”

Collaborative Effort

Each speaker cited the need for and benefit of collaboration between organizations. Deputy Secretary Poneman encouraged listeners to talk to others in the audience who might have similar issues with their organizations, saying peer communication is more important than hearing general diagnosis from experts. He also marked the issue as one the Obama administration was concerned with and praised the energy companies who have dealt with the office thus far. “We have found the industry to be extremely responsive. I think we’re going to have a very good partnership.”

Companies that are attacked should come forward, too, said Hayden. Sharing experiences of infiltrations is the first step to recognizing the scope of the problem. Since criminal activity taking place on corporate networks is a secret to the general public unless announced, there is not much public conversation about how to keep intellectual and physical property secure outside of a company’s individual efforts.

Hayden encouraged discussion about how “people with common values” who want the Internet to remain free-flowing but still safe for business might ask their governments to intervene, and observed that there are avenues a nation-state can take that would be illegal in the private sector. He cited a Jan. 27 Washington Post article, “Pentagon to boost cybersecurity force,” by Ellen Nakashima. The article is about the Pentagon’s launch of cyber teams to take the offensive in the battle, and Hayden noted the inclusion of “national mission forces” charged with “defending American critical infrastructure beyond American networks.”

But ultimately, vulnerability can only be reduced so far, and for some companies that effort has reached its practical limit. Hayden recommended businesses focus on diminishing the consequence of an incursion. “They’re getting through. They will penetrate your network. You can make it harder, more expensive, less robust, but they are going to penetrate.”

Comments