April 2013, Vol. 240 No. 4

Features

‘Perfect Storm’ Shines Light For More Infrastructure In New England

With what could be viewed ominously as the perfect storm bringing a much rougher winter than last year’s to New England, concerns about the need for additional natural gas infrastructure in the region have once again been dramatically underscored.

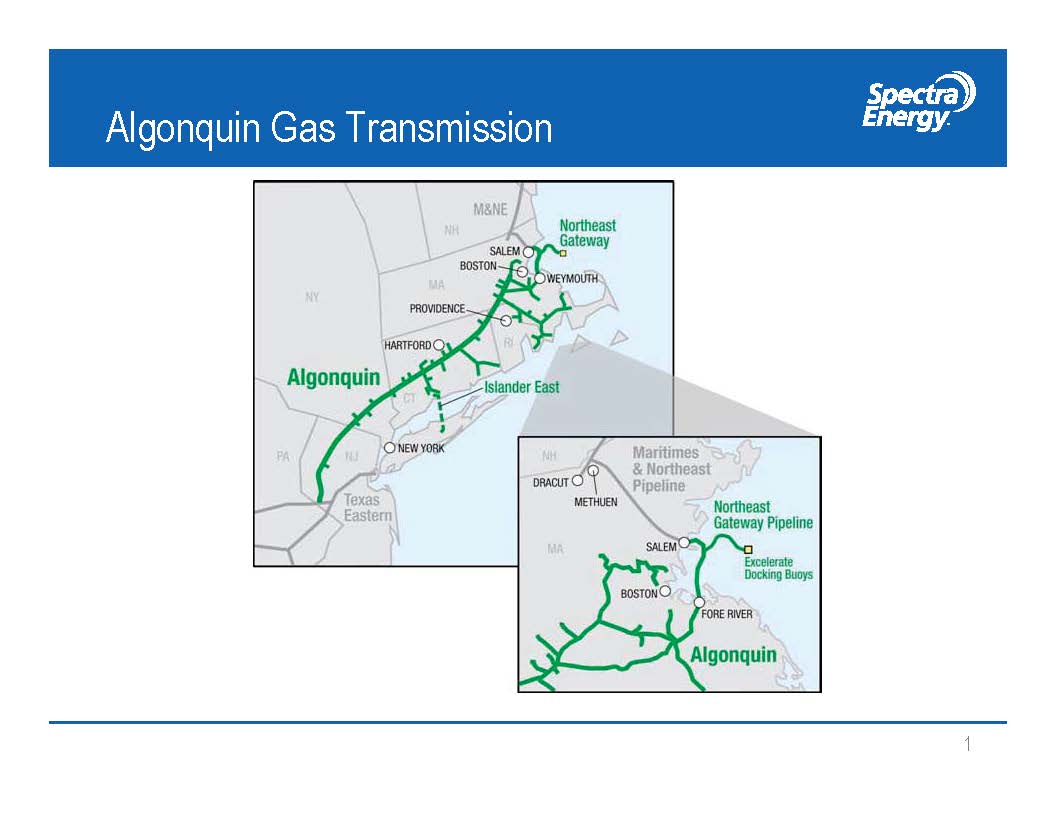

As severe weather helped drive energy consumption in recent months, the use of natural gas for power generation also climbed 3% between January and October 2012 in the Boston area, compared to the same period the previous year, according to U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) data. At the same time, gas flow from the west and south reached near-capacity levels on existing pipelines with the region’s primary supplier – the Algonquin Gas Transmission system – having operated at “high utilization” since mid-2012.

“It’s a pretty clear indication there is not enough pipeline capacity going into New England,” said Andrew Soto, AGA’s senior managing counsel of federal regulations. “That explains the basis differential – the value of moving gas into the region is so high, given the cold weather and the demand.”

Prices, too, have reflected this value and need for more infrastructure in New England’s spot market since November, with the Algonquin Citygate trading point selling at $2 more per MMBtu than is paid in New York City – historically comparable to New England prices – and $3 per MMBtu more than Henry Hub prices. And, according to ISO New England, which oversees the region’s electricity market, a megawatt hour cost about $150 in early February, compared to about $30 a year earlier.

“When you look at specific data points around the country, you don’t see a lot of price movement, even in what would be considered cold weather,” Soto said. “There is a tremendous amount of price stability at all the other points. This really is a localized phenomenon.”

Spectra Energy, owner of the Algonquin system, is looking to help meet the increasing demand for natural gas from home heating and electric generation, while lowering energy costs, with construction of the Algonquin Intermediate Market (AIM) expansion project. An open season on the project, with a contemplated expansion capacity of 450,000 Dth/d, was completed in November, drawing “robust interest” that Spectra is working to convert into “binding commitments,” according to Richard Kruse, company vice president of Regulatory Affairs.

Most of the work on the project, targeted for completion in November 2016, is expected to take place within existing rights-of-way and at company-owned facilities in Connecticut, Massachusetts and New York.

“What we have seen in the last couple of years is what has become a market that is as tight or tighter than New York City was, in terms of moving gas from the west to the east,” said Kruse, concerning the Boston area. “Of course, that’s all driven by the market desire to access Marcellus and relatively less-expensive gas.”

Much of the cost relief for New York City customers came last year when Spectra’s New York-New Jersey expansion was certified, sending gas prices down, based solely on the fact that the 16 miles of new pipeline and 5 miles of replacement pipeline to the company’s Texas Eastern Transmission and Algonquin Gas Transmission would be adding 800 MMcf/d of capacity in November 2013.

LDCs And Power Plants

With a number of midstream proposals on the table, “you have a pretty clear market signal that it’s going to drive further investments,” Soto said. The question then becomes, who’s going to hold the contracts and buy capacity on the future infrastructure?

“That’s where it gets a little complicated,” he noted. “A lot of the increased demand for natural gas in New England is driven by the power-generation sector, which has not traditionally relied on firm pipeline contracts.”

Data from ISO New England showed natural-gas fired energy generation has grown from 15-51% in the relatively short time between 2000 and 2011. Meanwhile, LDCs hold the vast majority of firm capacity on the Algonquin in order to ensure the winter needs of residential and business customers are met; during less-than-peak times of the year, LDCs release that excess capacity to other customers.

“Power plants have been one of the big markets taking advantage of that (LDC releases). Quite frankly, that’s probably a good ‘win-win’ for both customers,” Kruse said. “The challenge – and it’s an opportunity in our mind – is as natural gas has become the fuel of choice for new electric generation … these plants have been hooking up and are using natural gas longer and longer.”

One problem becomes obvious: Power plant operators now want to run at high-load factors during the winter – the same time LDCs are pulling back capacity. This creates a challenge for the electric industry, which needs the gas-fired generators to maintain the reliability of the electricity grid, but says its operators can’t afford the capacity because they aren’t paid enough in the electricity market.

Selling To The Grid

As a rule, power generators have sold energy to the power grid, or retained it, depending on how each particular company is set up. The rate for those transactions is negotiated in the market place. Historically, the Public Utility Commissions (PUCs) have not compensated utilities for the cost of constructing facilities.

At the far end of the cost spectrum, nuclear plants – which take roughly 10 years to construct with investments of between $5-7 billion – must make long-term investments without knowing the future price of the power the company will sell, or the level of rate increases that will be allowed.

“That dynamic has not been resolved and that problem exists for other types of power generation; it’s just the numbers are not as big as they are on the nuclear-side,” said Mark Bridgers, a design and construction consultant at Continuum Advisory Group. “If you want to see more facilities built, then you’ve got to change the ways that the utilities are compensated for the selling of that power.”

He suggested the best approach might be to allow for more accelerated cost-recovery or by formulating long-term arrangements structured similar to bonds that carry rate-structure guarantees. “The industry was set up to facilitate the investment of long-term assets. We are getting the exact opposite of that right now.”

Bridgers, however, was not optimistic about a consensus being drawn on a cost-recovery method, and Kruse opined that there are so many cost-recovery suggestions “surfacing in so many different forms, it’s hard to keep track of them.”

Said Bridgers, “The whole rate structure was essentially set up to get the utilities to be willing to put 50-year money in play with the recognition that they could do so with a reasonable return on that investment.”

Fast-forward to today and PUCs are regulating utilities in a way that essentially forces utilities to make no decision or, alternatively, make short-term, low-risk investments because the market is so dynamic, he said, adding that, with medium-sized gas facilities being built and online within a year, “there’s not any other solution for the future other than gas.”

Meanwhile, other movement on the infrastructure front in the region is already under way.

Summit Natural Gas of Maine won approval in January to provide natural gas to 17 communities in the central part of the state, along a roughly 20-mile pipeline between Augusta and Winslow that would tap Spectra’s 833,317 MMBtu/d capacity Maritimes and Northeast Pipeline. Gas service for homeowners and businesses closest to the mainlines is targeted to begin in late 2014.

Also on track, a Williams project in partnership with Cabot Oil & Gas and Piedmont Natural Gas that would develop a major pipeline project, connecting the Appalachian natural gas supplies in northern Pennsylvania with northeastern markets by 2015. The 120-mile Constitution Pipeline will have 650,000 Dth/d capacity, running along a 30-inch pipeline from Susquehanna County, PA to Iroquois Gas Transmission and Tennessee Gas Pipeline systems in Schoharie County, NY. In conjunction, Iroquois will develop the Wright Interconnect Project, an expansion of its existing compression and metering facilities in Wright, NY.

Separately, Portland Pipe Line has told Vermont lawmakers it would consider shipping tar sands oil from Western Canada across New England. CEO Larry Wilson told the state House Fish, Wildlife and Water Resources Committee “that is an option we would absolutely consider.”

Such a move would require reversing the flow of pipeline now carrying oil delivered by ship to South Portland, ME, then to a refinery in Montreal. However, this plan is already facing stiff opposition from environmentalists concerned about spills.

“Fundamentally, natural gas is abundant in North America and a reliable fuel,” said Soto. “When you see high prices in New England, that’s a localized concern, and that’s the market working to provide a price signal that says ‘more infrastructure is needed.’ The notion that ‘Well, we shouldn’t rely on natural gas because of the high prices,’ I think, is a false one. This is a market signal, and what it is telling us is that we need to build more pipe.”

By Michael Reed, Managing Editor

Comments