April 2014, Vol. 241 No. 4

Features

The Tortoise, The Hare And The Pipeline Project

Who doesn’t remember Aesop’s fable about the tortoise and the hare? The story concerns a hare who ridicules a tortoise that has challenged him to a race. The hare soon leaves the tortoise behind and, confident of winning, takes a nap midway through the course. When the hare awakes, however, he finds that his competitor has arrived at the finish line before him.

This story should resonate in the current world of pipeline projects, especially for companies that believe the return on some projects is so attractive it is better to shortcut critical definition tasks to reduce a project’s overall cycle time (time from the formation of the core project team to steady-state operations).

The problem is that frequently these “hare projects” are accelerated beyond the rate at which basic project data (a comprehensive set of parameters to govern the design of the project, such as product properties, routing, terrain conditions, hydraulics, etc.) can be acquired; community, right-of-way (ROW), and permitting issues be resolved; and best project management practices be implemented.

Shortcutting critical project-definition steps in the name of schedule is a risky business. It typically results in unpredictable results, which in turn significantly diminish – or even entirely wipe out – expected project returns. This is because the execution of “hare projects” usually ends up taking longer and costing more than planned because of unanticipated, but required, major late changes during execution.

Significantly slipping a promised in-service date also often results in a loss of market share and payment of liquidated damages to different stakeholders. Even under the most favorable shipping contract terms, the slip and overrun damage the reputation of the company developing the project, possibly hurting future business. Critically important, “hare projects” also achieve worse construction safety performance.

Using a carefully normalized database of nearly 1,900 pipeline and pipeline-related projects worldwide, Independent Project Analysis (IPA), Inc. has been able to statistically quantify why companies are better off allowing sufficient time to do project definition correctly. This approach yields better results because it enables project teams to progress the project slowly but surely at first, and then pick up the pace during execution by avoiding time-consuming and costly late major changes and reroutes. Think of it as the tortoise jumping on a skateboard about one-third into the course.

The first step to ensuring a successful pipeline project is – despite the sense of urgency – adherence to a proven project development process. A project development process not only provides an opportunity to select the right business opportunity to pursue among competing opportunities, but perhaps most importantly, it also establishes a framework to enable the correct sequencing of tasks, activities and deliverables to avoid changes and rework later.

Incorrect sequencing of activities is one of the root causes for “hare projects” to get sleepy. For example, it is risky to submit a permit for a route for which the ROW has not been negotiated; a project team could find itself at the end of the permitting line for a second time if the ROW for the original route cannot be secured.

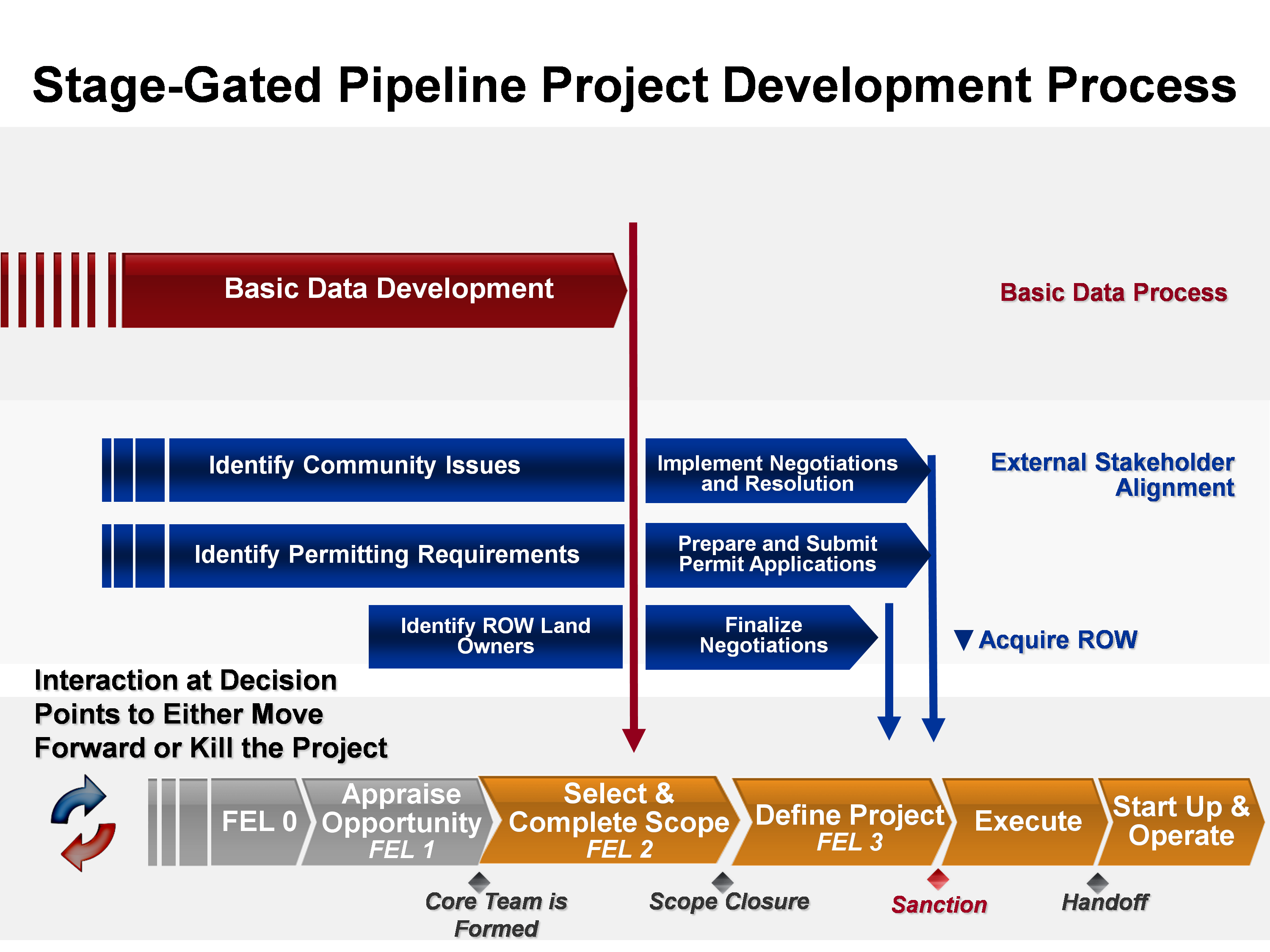

In addition, a stage-gated project development process contains decision points (or gates) to allow for reviewing of progress and revisiting the project’s feasibility as it becomes better defined. That is sensible if early production forecasts are uncertain and volumes to be transported by the pipeline are subject to change. Figure 1 indicates how basic data development and external stakeholder alignment feed into the typical stage-gated project development process for pipeline projects.

As shown in Figure 1, by the end of front-end loading (FEL) 2, project teams must have selected a single pipeline route, acquired and incorporated basic project data into the design, and identified community, permitting and ROW issues in sufficient detail to enable closing and freezing the scope.

Reaching scope closure at the end of FEL 2 is critical to the success of pipeline projects. IPA research indicates that starting FEL 3 (or the definition phase of a project) without completing FEL 2 is the root cause of projects that get delayed, recycled or canceled during FEL 3. Starting FEL 3 without completing FEL 2 is also a root cause for projects not meeting business needs after going into operation, as well as for projects that, despite having reached “best practical” definition at sanction, do not achieve competitive results.

The second step to a successful pipeline project is to form a multidisciplinary project team that has the authority to make most project-related decisions. For many pipeline companies this is easier said than done as increasing workloads, combined with a retiring workforce, are causing difficulties in adequately staffing projects.

As shown in Figure 2, lack of an integrated team results in a statistically significant increase in the number of changes during detailed engineering and construction.

The third step to ensuring a successful pipeline project is to reach a “best practical” level of definition by the end of FEL 3. According to the stage-gated process, the end of FEL 3 should coincide with project sanction. By this point, a project team must have advanced project definition in three key areas that IPA research has statistically correlated with better project performance.

These three areas make up the components of IPA’s FEL index, which is a quantitative measure of project risk. The three components of the pipeline FEL index are site factors, the project execution plan and engineering definition.

Of these components, it is the first two that typically lag optimal levels of definition for pipeline projects at sanction. In the case of the site factors, this is typically because advancing definition in environmental permitting, ROW and community issues often takes precedence over some of the other areas, with many projects failing to adequately define soil and terrain conditions and health and safety requirements early, resulting in changes to their sanctioned cost and schedule estimates.

In the case of the project execution plan component, gaps typically revolve around the lack of definition of the project schedule. As for other types of projects, meticulous project and resource planning is strongly correlated with more predictable and competitive pipeline project results.

Figure 3 shows the statistical relationship between the FEL index at the end of FEL 3 and the overall project cycle time for pipeline projects. The cycle time index measures the relative absolute cycle time performance consequently, how fast a project was relative to similar projects). A cycle time index higher than 1.00 represents a longer than average cycle time and an index of 1.00 represents an average cycle time.

As shown in Figure 3, better project definition (as measured by the FEL index) leads to faster overall project cycle time, confirming that the “tortoise on skateboard” approach to pipeline projects results in an overall faster project. Importantly, better project definition also leads to better construction safety, as shown in Figure 4.

As shown in Figure 5, adopting a “tortoise on skateboard” approach consistently results in more predictable execution schedules. On average, the “tortoise on skateboard” approach results in 33% less execution schedule slip over the “hare” approach, ultimately resulting in a 30% shorter cycle time duration.

Although choosing a slow but steady approach to pipeline project development might be frustrating for some at first, it is critical to stick to a proven sequence of activities, gain multidisciplinary alignment, and adequately define a project to mitigate risks before sanctioning it. It is also important to understand that staying in business is more than just about one race.

Taking the “hare” approach to pipeline projects is deceptively attractive at first, especially for those who do not fully understand or appreciate the complexities and multiple interfaces that pipeline projects entail. However, adopting a “hare” approach almost always guarantees that the project will have to stop for a nap only to find out when it awakens that it would have been better off had it chosen to take the “tortoise on skateboard” approach.

[1] Paul Barshop and Chris Giguere, Improving the Effectiveness of the Scope Development Phase, IPA, IBC 2006, March 2006.

[2] Andrew Griffith and Sarah Dunn, Improving Construction Safety Performance: Industry Trends, IPA, IBC 2009, March 2009.

Author: René Klerian-Ramírez is IPA deputy business area manager Hydrocarbon Processing and Transportation. He joined IPA in 1999 and focuses on pipeline clients. Klerian-Ramírez has applied IPA’s project evaluation system methodology to hundreds of capital projects worldwide, including many megaprojects. He holds a master’s degree from Georgetown University and a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from Universidad Iberoamericana.

Comments