August 2014, Vol. 241, No. 8

Features

LNG Buyers Continue To Seek Price Relief

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) buyers continued to show no love to sellers at the Gastech Conference and Exhibition held in South Korea recently.

“The price of energy has escalated 170% in the last five years for major Asian buyers,” said Sheng-Chung Lin, chairman of CPC Corp., Taiwan’s state-owned LNG importer. He added this has eroded the national competitiveness of five of the world’s dominant LNG buyers: Japan, South Korea, China, India and Taiwan.

Seok-hye Jang, chief executive of Korea Gas, the world’s No. 1 buyer of LNG, said the Asia standard of pricing LNG slightly below the energy-equivalent crude-oil price has resulted in the world’s highest gas prices and no longer makes sense.

“The Northeast Asian market has been burdened by the inflexible contract conditions and rigid pricing practices,” said Sang-Jick Yoon, Korea’s minister of Trade, Industry and Energy. “As a result, consumers in this region have been paying the so-called ‘Asian premium,’ which prevents both consumers and producers from fully enjoying the benefits of new opportunities.”

U.S. and Japanese gas prices are based on different fundamentals that became strongly apparent starting in 2009. U.S. prices depend on domestic gas production, marked in recent years by a flood of shale gas output. Japan LNG prices depend on oil markets, marked in recent years by very high prices.

“There are times that the old ways don’t work anymore. We need to get rid of the old and find new and better alternatives,” Jang said.

Sellers also spoke in force at the conference, noting the cold facts of the business from their perspectives: Tens of billions of dollars in upfront investments, spiraling construction cost escalation in the past decade and many new development opportunities, some of them in challenging, expensive locations.

Several speakers from international oil companies that produce LNG told the over 1,200 conference delegates that Asia LNG demand could grow 50-100% in the next decade. Sellers will need a price that justifies the long-term investments they must make to supply that demand, they said.

To some extent, the sellers didn’t rebut the buyers’ rhetoric head on. Philippe Sauquet, chief executive of Total Gas & Power, said Japan, Korea and Taiwan pay extra for LNG to secure a reliable supply because they lack their own fossil-fuel endowment. The way to keep the price reasonable? Develop more projects around the world so there’s ample LNG supply, he said.

Pierre Breber, president of Chevron Gas and Midstream, said sellers need a revenue stream that compensates for costs. But, he added, détente will come.

“I know we can find common ground. We’ve done it in the past,” Breber said.

Domenico Dispenza, president of The International Group of LNG Importers, said the Asian gas market lacks the competition, coherence and liquidity that developed over time in North America and Europe and has resulted in lower natural gas prices in those regions than in Asia, at least currently.

“Everybody knows the recipe (for a cheaper Asia LNG price), but the ingredients are not there,” Dispenza said.

Buyers Devise Plans

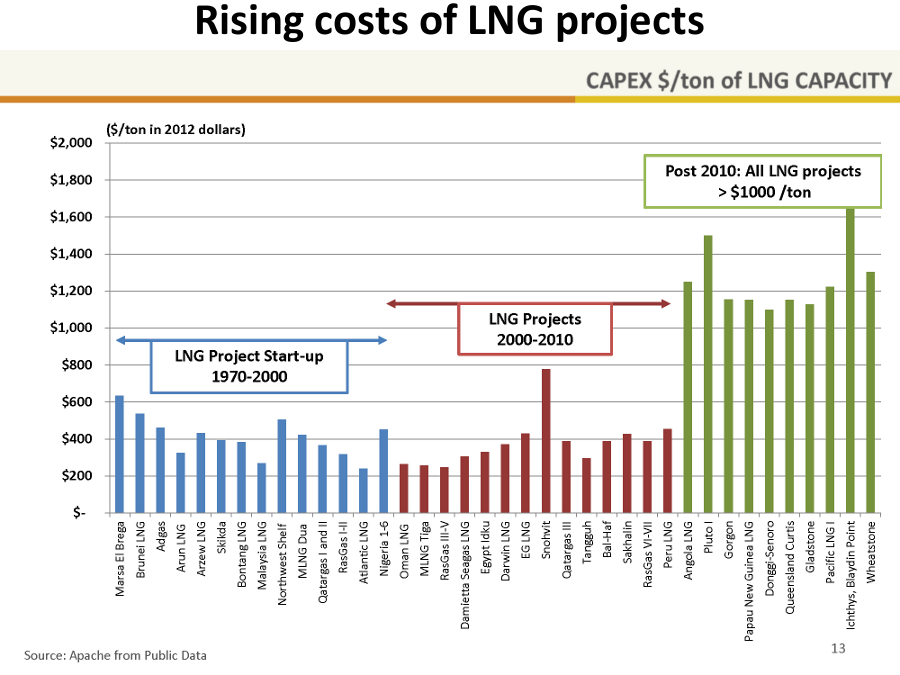

LNG project costs have skyrocketed on a per-unit-of-output basis. Controlling construction costs is a major challenge for developers of LNG projects. Many proposed U.S. projects (not shown on the chart), would be lower cost, as many would merely add liquefaction plants to existing LNG import terminals.

Buyers have been doing more than talk. They have begun investing in gas developments and LNG projects to secure supplies on terms that they can control. For similar reasons, they have contracted for LNG from Cheniere Energy’s export plant under construction in Sabine Pass, LA and from other planned U.S. projects.

While in South Korea for the Gastech conference, an executive with state-run gas supplier GAIL (India) signed an agreement with Japan’s Chubu Electric Power to explore buying LNG together in an effort to get better terms than either could gain alone. Other companies are considering similar moves, a Japanese official said. They might not get better prices, but they could win the option to send cargoes to more destinations, an improvement over current inflexibility over where they can take shipments.

Young-Sik Kwon, chief operating office of Korea Gas Corporation (KOGAS) Resources Business Division, said KOGAS has adopted a three-part strategy to achieve cheaper gas:

• Portfolio diversification – Using other kinds of pricing beyond oil-indexation, including gas purchased based on U.S. Henry Hub market prices; expanding its number of LNG suppliers; purchasing some volumes on a regular basis and some on a periodic basis to try to catch differences in short-term and longer-term pricing.

• Improve market efficiency – Invest in LNG projects; sign contracts that allow destination flexibility and cargo-swap arrangements so that LNG shipments can go to needier, higher-priced or more cost-effective markets. The traditional industry model is that a seller locks its buyer into long-term commitments to take deliveries only to specified locations. But, Kwon said, LNG shipping costs are rising as more projects are built farther from Asia, and new ways of handling shipments can hold down costs.

• Buyer cooperation – more joint purchases.

Kunio Nohata, senior general manager of gas resources for Tokyo Gas, had a similar three-point strategy:

• Diversify supply by buying from the proposed Cove Point, MD export plant in the United States.

• Diversify contract terms by incorporating destination flexibility and U.S. and European gas-market prices rather than strictly oil-indexation.

• Purchase LNG from Atlantic-basin LNG sources where prices might be lower even after paying extra shipping costs to Asia.

Nohata believes that U.S. LNG exports – which should begin from the Cheniere Energy plant in 2015 or early 2016, and from other plants perhaps as early as 2018 – will help lower Asian gas prices. U.S. exports will create an arbitrage opportunity between lower-priced U.S. LNG and higher-priced oil-indexed LNG, and it will stimulate more LNG flow between the Atlantic and Pacific, he said.

Three-point strategies remained in vogue at Gastech, as CPC Corp.’s Lin of Taiwan unfolded his company’s map showing the route to lower prices:

• Expand sources – Buyers invest in LNG and gas-pipeline projects, explore for domestic gas and contract with new suppliers.

• Enhance flexibility – Obtain destination flexibility in contracts, develop an LNG trading hub for Asia, get cost-of-gas-plus-liquefaction/transportation pricing, such as from U.S. projects rather than an oil-indexed price unrelated to the cost of gas production.

• Enlarge the market – Develop gas as a marine and vehicle fuel, petrochemical feedstock and bunkering fuel. More demand would prompt more supply, ideally lowering costs and prices.

Future Of Oil Indexation

Gastech participants also discussed subtle changes afoot in LNG purchase contracts due to buyer pressure.

Talk of softer “slopes” — the mathematical link between the LNG price and the oil price to which it is indexed. And of a possible return to favor of a price cap to protect buyers when oil prices are high and a price floor to protect sellers when crude is down.

Not all negotiations have gone in favor of buyers, however. The Yemeni government reportedly renegotiated a big price boost for its LNG from KOGAS in early 2014, for example. (The original deal, signed during a buyers’ market in 2005, resulted in some of the world’s lowest internationally traded gas prices – not just lowest LNG prices – and the Yemeni government was under strong public pressure to strike a new deal with Korea.)

A couple of Gastech speakers cast skepticism that talk in Japan, Korea, Singapore and elsewhere of establishing a Asia gas trading hub could become a viable pricing alternative to oil indexation anytime soon.

Chris Holmes, senior director for global gas and LNG at consultancy IHS Global, outlined how long the United States, United Kingdom and Europe took to develop their gas markets.

Short answer: Decades. Longer answer: Decades in each case, with a single government entity strongly guiding the industry’s bumpy path through deregulation.

Asia, with many countries, has fragmented jurisdictions, little integration of pipelines across borders, insufficient volume traded at present, lack of players active in the business, barriers to players wanting to enter the business, and a standard of doing business in which gigantic volumes get traded but not small volumes needed to bring in more trades, volumes and players, Holmes said.

So in the short- and medium-terms, expect oil-indexation for LNG prices to stick around, he said. Longer term? “Anything is possible.”

Also on the pessimistic side: Andrew Walker, vice president of global LNG for the UK’s BG Group, an international LNG supplier. Asia won’t have a true trading hub until it develops features lacking now, he said, including trading volume and flexibility, pricing indices that are transparent and trading instruments, such as those found on futures markets.

BG Group expects little change by 2025 in the volume of LNG without restrictions on where the shipments may go, despite the start-up of U.S. LNG export plants.

Where Holmes didn’t see much erosion in Asia of oil-indexation pricing, Walker didn’t see much change in fixed destinations for LNG shipments. He predicted that in 2025, even after U.S. LNG plants start exporting, flexible-destination volumes will total only about 15% of all LNG trade, about what it is now.

Ming Cai, a senior LNG analyst with energy consultancy Poten & Partners, discussed what happens to a utility’s portfolio of oil-indexed LNG when it buys cargoes priced on the historically volatile U.S. market.

Because lots of Asia utilities are poised to do just that, a considerable Gastech audience was intrigued about what Cai and his co-authors learned for their research paper.

Cai only partly satisfied them with his answer. Based on historic U.S. prices, adding some U.S. LNG to an oil-indexed portfolio will reduce overall price volatility, Cai said.

How much is “some”? Well, Cai and his co-authors considered many different scenarios from the past. But that was the past, and it was theoretical, kind of a laboratory setting.

“The real world is different,” he said, leaving his answer at that.

Author: Bill White is a researcher and writer for the Office of Federal Coordinator of Alaskan Natural Gas Projects. He can be reached at bwhite@arcticgas.gov.

Comments