March 2014, Vol. 241 No. 3

Features

Alaska: In Search Of An Energy Encore

The first thing to remember in analyzing Alaska is that every man, woman and child who resides there is in the energy business, thanks to a state oil tax-funded special investment fund that pays an average of $1,000 annually to every resident.

And the second truism is that engineering, technology and economics are only part of the answer to this bigger-than-life state’s energy future; politics and private investment decisions will make or break that future. It is a future at a crossroads in 2014.

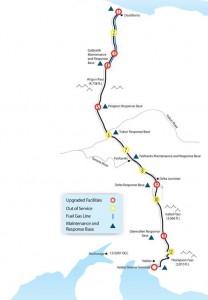

To understand where Alaska is going with its still-rich natural resources requires understanding where the state has been, not just since its oil production peaked at the 2.1 MMbpd level in 1988 but particularly the last 10 years, during which throughput in the 800-mile North Slope to Valdez Trans Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) has declined by 6-8% annually, taking volumes on average down to the 590,000 bpd level in 2011 and much lower in 2013.

Steadily rising oil prices during the past 10 years have allowed for increasing revenues from oil due to the Alaska’s Clear and Equitable Share (ACES) law, despite declining total production each year going through TAPS. From the industry’s viewpoint, however, ACES has discouraged new producers from investing in the North Slope and the pipeline decline has become precipitous.

Typically, oil contributes about 90% of Alaska’s state revenues. (There is no state income tax on individuals and no state sales tax.) For the most recent fiscal year, 2012-13, oil accounted for 92% of the revenues.

“For every direct job at an oil and gas company, there are nine more jobs generated in the state, and no other industry in the state has that kind of multiplier effect,” said Kara Moriarty, executive director of the Alaska Oil and Gas Association. “Economists estimate that our economy would be half the size it is today without oil/gas. So, the bottom line is that we fuel the economy here; we’re the backbone of the economic foundation in the state.”

Residents and policymakers for years have been debating how new oil and gas can be pulled out of Alaska and what the economically viable life is for TAPS, not to mention the longevity of its physical infrastructure. The latest culmination of the debate is a new state law – the “More Alaska Production (MAP) Act,” or SB 21 – passed in 2013, but facing a statewide referendum in August when Alaska voters will decide whether to keep the new law or go back to ACES.

Intertwined with this are a host of issues and sub-issues related to both oil and natural gas, the future of energy jobs in the state and the viability of the state’s annual operating budget. So far, Gov. Sean Parnell has led the move to ease the tax burden on the oil and gas industry to stimulate more production and actually help it to grow, adding energy infrastructure and state revenues.

According to Mark Myers, vice chancellor for research at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks and a former head of the U.S. Geologic Society (USGS), advocates for SB 21 argue the state has to take the cuts in order to provide more incentives to step up production. Meanwhile, opponents say the added production the measure will incent won’t produce enough added revenues to make up for the cuts.

According to Mark Myers, vice chancellor for research at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks and a former head of the U.S. Geologic Society (USGS), advocates for SB 21 argue the state has to take the cuts in order to provide more incentives to step up production. Meanwhile, opponents say the added production the measure will incent won’t produce enough added revenues to make up for the cuts.

“Those are sort of the end points in the arguments,” Myers said.

At the end of 2013, Parnell, a strong backer of SB 21, seized on the 2014 investment plans by major Alaska oil and gas producers and TAPS owners as a positive sign that the new law was working. BP plc promised an additional $1 billion in investment in the next five years, and ConocoPhillips plans to raise its capital expenditures (capex) in the state by more than 50% in 2014.

“[This] announcement is further proof that the MAP Act is working,” Parnell said. “Billions of dollars in new investment have been announced since I signed the MAP Act into law, and it’s helping to keep Alaska’s businesses and workers busy as they go after new oil production. Alaska is on track for more oil in the pipeline and more opportunities for future generations.”

Parnell also was signaling the fact that in a gubernatorial election primary this year SB 21 is going to be an issue that will command debate on the state’s energy future, which until recently was viewed as in decline. Alaska, since 2011, has fallen to the fourth-largest oil producing state, having been passed by upstart North Dakota, which is now No. 2 behind Texas, and rebounding California.

“In a state as large as ours, with lands as large as ours, it is a little bit embarrassing that states like North Dakota and California have overtaken us in oil production,” said Joe Balash, commissioner in the Alaska Department of Natural Resource (DNR) and a bullish advocate for major multibillion-dollar natural gas and oil projects. Balash said he envisions Alaska a decade from now restoring the TAPS oil flows to the 1 MMbpd level and billions of cubic feet of natural gas being exported from the state to the energy-hungry Asian nations in the Far East.

Balash said he thinks a sort of “wounded pride” among Alaskan leaders in the past couple of years helped draw support for Parnell’s SB 21 as a means of turning around TAPS and the state’s perceived energy decline, although some earlier incentives by state lawmakers on natural gas supplies in the Cook Inlet already have brought about a resurgence of exploration and production (E&P) in that area. This prompted ConocoPhillips to file for a federal permit to resume exports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Japan after a several-year suspension of those exports from the nearly 50-year-old LNG facilities on the Kenai Peninsula in the south.

In late 2011, an Alaska Superior Court judge, Sharon Gleason, assigned a $9.25 billion value on TAPS for tax purposes and determined that the oil pipeline had at least another 50 years of life as part of a 2009 case for which there are appeals pending in the Alaska Supreme Court. At the end of 2013, there was no sign the state’s high court would act anytime soon.

“No date has been set for oral argument in the appeals of Gleason’s 2011 decision regarding 2007-09 TAPS property tax appeals,” said a spokesperson for Balash, adding that the court is looking at an oral argument date for some time in April 2014.

Energy officials in Alaska are not complacent about the resource base, even if the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) and its 10.4 Bbbls of recoverable reserves remain off-limits as it was last year when the Energy Information Administration (EIA) published its latest national forecasts.

“My view as a geologist is that the resource base is very significant,” Myers said. “It is really a question of what the production profiles are from the existing fields, and how much heavy oil and new exploration oil comes into the system, and how long it takes it to come in.”

EIA regional expert Philip Budzik said in past writings the Arctic could hold up to 22% of the world’s undiscovered conventional oil and natural gas resources, with a preponderance of gas compared to oil. But there is a dark side to these projections, Budzik said, ticking off four drawbacks:

• The Arctic resource base is mostly gas and gas liquids.

• Arctic oil and gas resources will be considerably more expensive, risky and take longer to develop.

• There are still unresolved Arctic sovereignty claims that could delay or preclude development.

• Protecting the Arctic environment will be costly.

There is plenty of shale oil and gas potential in the North Slope, but so far there has been little exploratory drilling and only two real serious potential producers, both relatively new entities that bought up lease holdings in 2010 and 2011. At least two companies, Alaska-based Great Bear Petroleum and San Diego, CA-based Royale Energy Inc., have indicated they may step up exploration activity on leaseholds in the North Slope in 2014.

“At certain depths we know where hydrocarbon windows are on the North Slope as they are very rich in organics and very oil-prone, and they’ve been major generators for Prudhoe Bay and the other resources,” Myers said. “They all fit in a belt in the central part of the North Slope, swinging over state lands and the pipeline corridor, so it is a very large area and contains a lot of the remaining oil, but the question is – can you produce it economically?”

Balash said he thinks Alaska has a rich history of technological advances since TAPS was first conceived, pointing out that the original reserve estimates for Prudhoe Bay were 14 Bbbls, of which 6 Bbbls were designated as recoverable.

“To date, there have been more than 16 Bbbls recovered,” Balash said. “We think that [technological advances] will continue as the companies’ understanding of the resources improves and new technology is made available. There is more use of complex, multi-stage fractures that are similar to what is being done in the Lower 48, but in a more sophisticated way.”

He cited Dallas-based Pioneer Natural Resources in particular in its leaseholds. The company was acquired by Caelus Energy, a privately held firm, headed by Texas-based Jim Musselman, a lawyer-turned-oilman who formerly was CEO at Kosmos Energy.

So, technology is not a challenge to the future energy infrastructure needs in Alaska – neither the TAPS regentrification nor the development of more statewide natural gas production, and transmission and distribution pipelines. This year marks the end of a decade-long electrification and automation project for TAPS. The history-making oil pipeline has modernized its pump stations, making them what the Alyeska operating staff call more efficient and “scalable.” The final pump station (PS1) will complete these changes soon, according to pipeline officials.

“We are working on a number of other renewal projects along the pipeline and at the Valdez Marine Terminal,” said Michelle Egan, a spokesperson for Alyeska and its CEO Tom Barrett, a former U.S. Navy admiral. “Much of the work is related to low throughput conditions,” including options such as adding heat, withdrawing all water from the oil before it enters TAPS, added pipe pigging facilities, and bringing pipe above ground for inspection.

The Low Flow Impact Study (LoFIS) completed in mid-2011 examined decreasing TAPS throughput down to 350,000 bpd, and the continuing work on “cold dry flow” technology (see “Going With The Flow In TAPS”) looks at volumes that are even lower.

“At some point, batch or intermittent operations may be needed to continue moving oil, and all of this is dependent upon proving the cold dry flow theory via the currently ongoing study,” Egan said. “For today’s operation, adding heat to keep the [lower volumes of] oil temperature above freezing as it travels 800 miles is the biggest effort.”

Egan said the tinkering with TAPS is expected to continue for years. “The option of transitioning to a cold dry flow [water withdrawal] system is being studied aggressively.”

Meanwhile, in November, Alaska’s DNR released what it called an in-depth study of the commercial aspects of a massive, $45 billion LNG export project that three North Slope producers and TransCanada Corp. are pursuing. DNR hired Black & Veatch to compile what turned into a 191-page Alaska North Slope Royalty Study, which included a recommendation that the state at some point take an equity share in the undertaking.

“The state ownership discussed in the state royalty study is an important consideration for the business case as the Alaska LNG project continues to make favorable progress,” said an Alaska spokesperson for BP plc, the majority owner in TAPS. “It will take all parties working together, including the state, to make this project feasible.”

DNR’s Balash indicated that while the major focus is still on TAPS future, the LNG project also is vital to rekindling robust growth in both oil and natural gas production on the North Slope. So, to that extent, there is synergy in finding both oil and natural gas solutions for Alaska’s future.

He sees a bigger economic role by the state in the future development of the Alaskan energy resources, and further major political and regulatory action by the state and federal governments. While Balash knows Alaska’s future involves a complex combination, including extending of TAPS’ operating life, finding new state oil resources and establishing a new system of the state taxing these resources, he also gladly talks about a need for new technological innovations and a surge of entrepreneurial-spirited E&P people in the state.

The University of Alaska’s Myers offered the caveat that a lot of the North Slope gas in the Prudhoe Bay field is re-injected to aid the pressure maintenance for oil production. Thus, a sudden surge of gas production from the field could jeopardize longer-term oil supplies, making the timing and volumes of gas production critical to future oil production.

In addition, Myers pointed out that in other fields there are further oil-gas coordination considerations. Point Thomson, for example, has vast natural resources, including gas hydrates, so it becomes a focal point for how the gas supplies are extracted to minimize the negative effect on oil production.

“On that field, if you pull the gas out too early, you will lose the majority of the oil just by the nature of the field,” Myers said. “The pressure depletion of the condensate field means the liquids come out of solution and some of those liquids are not recoverable after the gas is produced. That field is extremely sensitive to how you produce it, more so than Prudhoe Bay at this stage.”

Balash and the state are putting out the welcome mat for savvy energy investors and experienced oil and gas workers, engineers and technicians. Long before the ink was dry on the latest LNG project proposals, Alaska lawmakers endorsed a training strategic plan to ultimately provide training to local residents who want to get a crack at the LNG project jobs. It identifies “four broad strategies” to address the state’s projected needs inherent in the existing labor skills gap.

Among other things, the strategies call for “a comprehensive, integrated career and technical education system.”

The former USGS chief Myers said the best scenario for all Alaskans is to have viable gas and oil projects ongoing simultaneously. If this can be pulled off on the North Slope, the combined economics should look much better.

“I don’t think there is much disagreement about that,” he said.

But on a long list of thorny issues, there is still no consensus. Still unresolved are complex questions about the political solutions needed, legal questions about the proper valuation of existing and proposed new projects, economic debates about whether the state takes its royalties in-kind or foregoes them altogether, and coordination between state and federal agencies that control large chunks of the North Slope.

“In the aggregate, there is plenty of gas on the North Slope to handle the 42-inch proposed pipe for the LNG project,” Myers said. “It’s a 3 Bcf/d project so I don’t think it is much of an issue, particularly if it comes from multiple reservoirs.”

How, when and where the gas is extracted has some profound geologic and ultimately economic impacts, he cautioned. These are well-known by operators, but perhaps less understood by policymakers.

A key part of the infrastructure and investment decisions is the geology of the North Slope. There are both heavy and light oil supplies, vast natural gas supplies in some places where production would have negative impact on oil supplies, and there is shale.

Geologically savvy folks like Myers differentiate between the heavy North Slope supplies and tar sands supplies in Western Canada. “It is not a manufacturing process [a la tar sands]; it is oil/gas production,” he said, adding technology exists to produce the heavy stuff, which sits shallower, above the bulk of the North Slope light crude.

“It is a matter of whether we can make the production well bores last longer. The prize is really big – easily 5 Bbbls recoverable economic resource there,” Myers said.

Brent Sheets, research manager in the Center for Energy and Power at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, said he thinks heavy crude oil on the North Slope is abundant, but there is not the proper technology available to tap into it as a means of refilling TAPS.

“Obviously, one way to fill the pipeline is to drill more wells, but we don’t currently have the technology to economically go after that oil,” Sheets said. “The viscous [heavy] oil on the North Slop is the other part of a huge supply, but what a shame it is that the heavy stuff is literally on top of the light, sweet crude oil that is being produced.

“We drill right through that zone to get to the lighter oil below, so you could increase oil production [theoretically] without increasing your footprint. But you have to have the technology to do that, and we don’t at this point.”

Sheets said when he was head of the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Arctic Energy Office there were research projects examining that technological conundrum but those have expired. It is being left to the private sector, and he is unaware of anything ongoing. Ever the optimist, though, Sheets added the world in the oil industry can be turned upside down in a two-year span.

One way or another, expanded production of oil and natural gas and an expanded infrastructure to accommodate the growth are keys to Alaska’s future and bigger payoffs for its residents. It’s a future still very much in the formative stages.

Author: Richard Nemec is the West Coast correspondent for P&GJ in Los Angeles. He can be reached at rnemec@ca.rr.com.

Comments