October 2014, Vol. 241, No. 10

Features

Mexicos Energy Reform: Ready To Launch

Mexico is poised for an energy renaissance. It has ample reserves of oil and natural gas, experience in energy production, promising economic fundamentals, and industrial expertise. In recent decades, Mexico has suffered from declining oil production, insufficient gas supply, and high electricity prices.

The fundamental obstacle to Mexican energy development was mustering the political will to allow the country access to the expertise, technology, and capital needed to open new energy frontiers. Mexico’s leaders have now decisively found the will to reform and passed a set of laws that can transform Mexico into a major energy and industrial power.

The initial, constitutional-level reforms were passed on Dec. 18, 2013 and are discussed at length in an Atlantic Council report we released shortly thereafter, titled Mexico Rising: Energy Reform at Last? This constitutional framework has been translated into law with the signing of 21 implementing, or secondary, laws impacting oil, gas, power, and energy finance on Aug. 11, 2014. Our initial report asked: would Mexico undertake “energy reform at last?” We have now dropped the question mark. The legal fundamentals are now in place, and the Peña Nieto administration is ready to launch their implementation.

Our latest Atlantic Council report, Mexico’s Energy Reform: Ready to Launch, demonstrates that the secondary laws provide a compelling framework for growth across the energy sector. The vital upstream oil and gas reforms will allow private investment alone and alongside national champion Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX).

While the reforms provide that hydrocarbons in the subsoil will remain the property of the Mexican state, companies can book reserves for financial reporting purposes and enjoy competitive licensing frameworks to access what promises to be robust auctions of deepwater, tight formation (or unconventional) heavy oil and shallow water acreage. Mid- and downstream operations (pipelines, storage, petrochemicals, and motor fuel stations) will be opened to competition as well.

New independent operators will foster competition in gas markets under supervision of a new regulator for the management of gas pipeline planning and access (National Center for Natural Gas Control – CENAGAS) – while a reformed Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE) will be responsible for market regulation. The electricity law should, within two years, create a competitive power market managed by an independent system operator (National Energy Control Center – CENACE).

This new regime will include incentives for private capital to build new lower-carbon generation systems that welcome private investment in transmission and distribution under contract to the national power company, the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE). New laws governing PEMEX and the CFE convert these former monopoly players into what the constitutional reforms term “state-owned productive enterprises,” with substantially more independence but also subject to competition with private investors.

It remains undetermined how attractive Mexico’s offerings will be, especially in upstream oil and gas, until these contracts, their fiscal terms, the local content targets, and the quality of the acreage offered for development are known. The government will need to promulgate regulations fast and well if bid rounds are to be launched in the first half of 2015.

Much analysis on the reforms focuses on the upstream. However, the political and economic implications of success in the midstream and power sector reforms justify detailed analysis as well. The political sustainability of the reform relies on broad-based economic growth. This growth is tied to increased adoption of natural gas in Mexico’s energy mix.

Allowing market pricing of gas should increase supply and expedite the large-scale conversion of oil-fired power plants to natural gas, the build out of gas distribution infrastructure, and the provision of lower-cost electric power. Increased natural gas supply is critical to meeting future energy demand, lowering power prices, lowering carbon emissions, decreasing the Mexican government’s considerable power subsidy obligations, and expanding Mexico’s industrial base.

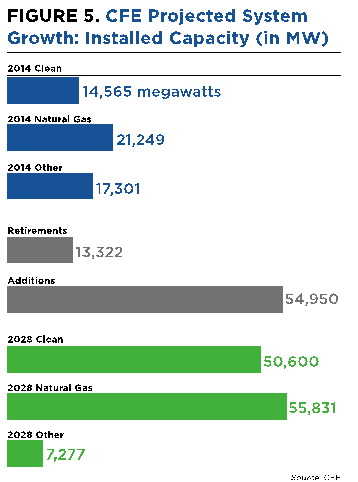

Mexico now has an ambitious plan to double its installed generation capacity by 2028, to 110,000 MW, largely fueled by the addition of over 50,000 MW of natural gas-fired capacity (see figure below). CFE has plans to build a network of midstream natural gas pipelines to transport natural gas from the United States, domestic gas from Mexico’s prospective shale fields, and imported liquefied natural gas to satisfy projected demand of 7.7 Bcf/d by 2028 for CFE alone.

CFE is tendering $2.2 billion of natural gas pipelines to enter commercial operation in 2016-2017, together with over 1,600 MW of new gas-fired capacity to be fueled by them. CFE also recently announced plans to convert seven plants totaling 4,600 MW from oil to gas at a cost of $300 million over 2014-2016. The energy reform is intended to provide incentives for additional midstream gas investment by CFE and PEMEX, which together control over 90% of Mexico’s gas pipeline capacity, and private sector actors.

A primary aim of the secondary laws is to foster a competitive gas market. To achieve that end, the laws limit vertical integration of natural gas companies and install CRE oversight of all retail gas marketing. Mexico wants to ensure competitive pricing for natural gas, and one way to accomplish that goal is to ensure that the companies cannot dominate both transportation and distribution.

This healthy caution may also prevent PEMEX or even CFE from exerting a monopoly position. A pillar of this effort is a new independent CENAGAS. CENAGAS will be responsible for managing the national integrated system of gas transportation and storage and for planning its expansion, subject to the approval of SENER with advice from CRE, which also regulates the system. The stated intent is to avoid market domination by regulating open access to gas pipelines, requiring the marketing of any unused capacity, and imposing consistent transportation tariffs, with the expectation of providing transparency over gas allocation.

Investor confidence that Mexico’s energy transformation will take place will enable the country to quickly attract the capital necessary to spur near-term macro¬economic growth long before oil and gas flows appreciably increase. Mexico’s quality of governance now places it at the top of class of emerging economies. President Peña Nieto has signaled his keen awareness of the need for speedy implementation with the announcement of a rapid action implementation plan (see below), or Energy Decalogue, the day after the secondary laws were signed.

Rapid Action Implementation Plan

- PEMEX’s Round Zero has been expedited. The Secretariat of Energy (SENER) announced on August 13, 2014, the assignment of exploratory areas and production fields that PEMEX will be able to retain, although the law gave the agency until the second half of September to make the decisions.

- Round One. The areas which will be part of the first round of the public bidding process will be announced expeditiously so that domestic and foreign private investors can begin their due diligence. The bidding process will begin in 2015. PEMEX has already announced the first areas in which it will seek joint venture partners.

- At the end of August, decrees were issued for the creation of CENACE and CENAGAS—both decentralized agencies under SENER—to consolidate the electricity market and introduce the new model for the natural gas industry.

- The Senate will receive the names of candidates for all new regulatory bodies, independent directors of Pemex and CFE, independent members of the Mexican Petroleum Fund for Stabilization and Development, and commissioners for the National Hydrocarbons Commission and the Energy Regulatory Commission. The boards of PEMEX and CFE will also be installed.

- The Mexican Petroleum Fund will be created, and decrees will be issued for the formation of the public fund, to promote the development of suppliers and contractors of the SENER-NAFINSA Fund, to advance state involvement in production projects, and to create the Universal Electrical Service Fund.

- The program to train specialists in the energy sector will begin, with the participation of SENER, the Secretariat of Public Education, and the National Council of Science and Technology.

- In October, the set of initial, higher-level regulations related to the secondary energy law will be published to allow time and full legal certainty for new investments in the sector.

- In October, a decree will be issued to restructure and modernize the Mexican Petroleum Institute, and to strengthen its mission as a national body for research and development of the industry.

- In October, the guidelines for the issuance of Certificates of Clean Energy will be published with the necessary incentives for the development of these sectors.

In the following 90 days, regulations will be issued for the National Industrial Safety and Environmental Protection Agency to ensure the sector complies with the best international practices in the field of industrial safety and environmental protection.

The success of the reforms now rests squarely on these implementation decisions. It is a formidable task requiring a level of administrative speed and savvy that would challenge any government, but over the past 12 months Mexico has shattered expectations. That gives confidence that these reforms will succeed. Mexico has made tremendous strides in addressing the questions that emerged following the constitutional amendments.

In our earlier paper, we identified seven principal questions. The secondary laws answer three of those questions – would the laws truly liberate PEMEX to act independently, would the fiscal framework trust the market, and would local content requirements be manageable? – in the affirmative. Two others – can Mexico offer competitive fiscal terms, and can it build effective regulators? – now have solid legal foundations and committed political leadership. So, we are optimistic. The final two questions – can the Peña Nieto administration manage public expectations and can it offer a compelling value proposition for electricity sector investors – remain to be addressed.

In coming this far, Mexico has accomplished an amazing political feat by passing comprehensive energy reform. Despite the heavy burden on the Peña Nieto administration to implement these reforms, it has exceeded expectations every step of the way. The budgets and staffs of the Ministries of Energy (SENER) and Finance and Public Credit (Hacienda), and the National Hydrocarbons Commission (CNH, Mexico’s upstream oil and gas regulator) have increased this year and next, with significant budget for CNH to hire outside advisers for legal and other support. Ministry and regulatory officials fully understand the challenge ahead – and the need to be flexible and quick to accomplish their goals.

Mexican Energy Reform Moving Forward: Key Steps

- PEMEX’s Round Zero has been expedited. The Secretariat of Energy (SENER) announced on August 13, 2014, the assignment of exploratory areas and production fields that PEMEX will be able to retain, although the law gave the agency until the second half of September to make the decisions.

- Round One. The areas which will be part of the first round of the public bidding process will be announced expeditiously so that domestic and foreign private investors can begin their due diligence. The bidding process will begin in 2015. PEMEX has already announced the first areas in which it will seek joint venture partners.

- At the end of August, decrees were issued for the creation of CENACE and CENAGAS—both decentralized agencies under SENER—to consolidate the electricity market and introduce the new model for the natural gas industry.

- The Senate will receive the names of candidates for all new regulatory bodies, independent directors of Pemex and CFE, independent members of the Mexican Petroleum Fund for Stabilization and Development, and commissioners for the National Hydrocarbons Commission and the Energy Regulatory Commission. The boards of PEMEX and CFE will also be installed.

- The Mexican Petroleum Fund will be created, and decrees will be issued for the formation of the public fund, to promote the development of suppliers and contractors of the SENER-NAFINSA Fund, to advance state involvement in production projects, and to create the Universal Electrical Service Fund.

- The program to train specialists in the energy sector will begin, with the participation of SENER, the Secretariat of Public Education, and the National Council of Science and Technology.

- In October, the set of initial, higher-level regulations related to the secondary energy law will be published to allow time and full legal certainty for new investments in the sector.

- In October, a decree will be issued to restructure and modernize the Mexican Petroleum Institute, and to strengthen its mission as a national body for research and development of the industry.

Source: El Universal

Looking ahead, with major political compromises now behind them, Mexico must take six urgent steps to ensure the success of the reforms.

• Ensure fiscal and contract terms are competitive. Hacienda’s discretion in setting fiscal terms, CNH’s contract language, and the Economy Ministry’s local content definitions of targets and eligible content will determine the success of the early bid rounds. All must show market savvy in tailoring terms to differentiate the diverse risk profiles of acreage offered, return long-term value, and be competitive with what Mexico’s peers offer.

• Let PEMEX evolve. PEMEX must be allowed to become an efficient company and not the government’s policy instrument. PEMEX enters into a new competitive marketplace with tremendous advantages, but it also remains vulnerable to political and bureaucratic interference. PEMEX must be allowed to improve efficiencies, allocate capital according to its own strategic planning, and not be required to take on investments dictated by the government. PEMEX must also focus on its core mission. Recent indications that PEMEX may secure its own drilling, logistics, worker hotel, and tugboat companies suggest the challenges of moving beyond its monopoly perspective.

• Build regulatory capacity. CNH, CFE, CENAGAS, and CRE must grow their internal staffs to manage the increased workload and promulgate new, best-in-class, implementing regulations quickly. This is a goal President Peña Nieto embraced when he announced that all regulations will be promulgated by October 2014 to encourage quicker private investment. All of these agencies will need significant external assistance in the coming months to meet this task. Meeting these needs is on track: Hacienda is adding up to 80 personnel into a dedicated unit, CNH’s 2015 budget will be five times higher, and CRE’s two times. Supplemental budget financing has also been provided for the remainder of 2014.

• Issue implementing regulations quickly. A near-term spike in interest, including in conversion of existing service contracts, should be expected but no serious investment will reach scale until the regulatory framework is clear. All of the rules for oil and gas exploration, energy transportation, and safety and environmental protection must be tailored for a system with nongovernmental actors. Although the Mexican government is likely already at work on these, it is a formidable task. Rules must be consistent with the newly drafted laws, efficient in practice, and be promulgated quickly. For example, the details of how people, goods, and services can be brought into the country will determine the cost structure (or economics) of operating in Mexico. The length of time it takes to get a permit for operating will determine when work – and the economic stimulus the population expects – will begin.

• Develop the electricity sector reform strategy and expedite regulations. Establishing clear and transparent regulations over access to gas and transmission for private generation will be critical to encouraging private investment in generation in a market currently dominated by CFE. The Mexican government should lay out a roadmap with clear milestones and timetables to make the power sector strategy clear. These could include provision of detailed open access rules; the pricing regime for transmission and gas pipelines; and the plans for the buildout of transmission and pipeline capacity. Beyond the regulations, the actions of the government and the regulators in the initial phases of the transition will be key to demonstrating that the legislation has teeth, that open access will be provided, and that the regulators will exercise their powers independently to ensure a competitive environment. Further information on the renewables policy and on subsidy retargeting will also be crucial to investors’ analysis.

• Create a security strategy for energy investment areas. Mexico’s internal security and the success of energy reforms are intertwined. The government needs to publicly describe how it will secure pipelines, areas of onshore exploration, and land bases for deepwater development. So long as risk premiums around security are high, production will lag and government rents will be low.

The United States has deep interests in Mexico’s prosperity, security, and stability and can speed the success of the reforms. At the same time, the United States must be sensitive to Mexico’s sovereignty and historic skepticism of foreign investment. The United States should be prepared to help in three ways if Mexico seeks cooperation:

• Facilitate regulatory harmonization on North American energy integration. Mexico’s energy reforms will eventually invite further integration with the United States and, by extension, Canada. Rationalizing natural gas, crude oil, product, and electricity trade will be increasingly important as Mexico increases production, demand, and further links to Central American markets. Crude oil should be an area of early examination. The United States retains a need for imports of heavy oil and Mexico needs lighter oils to blend with its crude streams to create more marketable exports to the global market. These requirements beg for clear rules for swaps of oil and re-exports of oil and gas. In addition, cooperative investment on natural gas transportation could enhance Mexico’s role as an energy bridge to the Americas. Trilateral dialogue, including the potential for a natural gas network from Calgary to Colombia, should be on the agenda for the 2015 North American Leadership Summit.

• Fast track gas pipeline border crossings. The United States should facilitate gas trade with Mexico, which is a near-term priority since increasing its domestic production will take some time. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission should increase its capacity to issue cross-border pipeline permits given the likelihood of increased Mexican demand for U.S. gas. State-level authorities must also be prepared for an increase in pipeline permit applications.

• Offer technical assistance if requested. While it may seem obvious, the long regulatory experience in the United States could be of use to Mexico. This means making U.S. regulators privately available to engage with Mexican officials and provide lessons learned and assistance to Mexican agencies and regulators as they begin efforts to draft regulations and implement reforms.

The succession of structural reforms Mexico has produced is transforming its international stature. Effective governance, even if mediated by robust political competition, is on the rise and Mexico can become a significant new magnet for foreign investment. The energy sector itself will attract foreign investment, but the prospect of lower-priced and more reliable electric power, plus a recovering U.S. economy to supply, will give investors in non-energy sectors confidence that Mexico will be a manufacturing destination of choice.

Mexico’s revival will also positively impact global energy security. Market analysts who projected Mexican production declines will now factor in rising production, creating downward pressure on the need for OPEC production and oil prices more broadly, and positioning Mexico to take advantage of rising demand across the Pacific. Mexico’s deepwater program should produce significant volumes by 2025, the point at which many forecasters have targeted as the peak of U.S. unconventional production. Mexico, therefore, will become a strategic supplier of oil just as U.S. production plateaus, extending the run of North American energy self-sufficiency at an optimum moment.

With a constitutional mandate, a comprehensive legislative framework, and impressive and courageous leadership and governance, there are no question marks left on whether Mexico’s energy reform will proceed. The countdown is over. Mexico is ready to launch.

Comments