May 2015, Vol 242, No. 5

Features

Making the Best of Evolving Midstream Infrastructure

The changing oil production and consumption landscape in North America has led to new developments in the infrastructure that brings oil to market – the pipelines, gathering systems, storage facilities, rail networks and marine-based transport networks that comprise the industry’s midstream oil infrastructure.

Realizing the full benefits of the continent’s vast oil resources requires developing and maintaining safe, efficient and cost-effective midstream infrastructure. The Energy and National Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSSI) recently released a report, Delivering the Goods: Making the Most of North America’s Evolving Infrastructure, that provides a snapshot of the changes in the continent’s midstream infrastructure and a host of important policy considerations that may ultimately enhance the benefits of increased North American oil production.

The report serves as a guide for industry and policymakers who seek to understand the strategic context and status of the debates to be had around each issue.

Changes underway in the North American midstream are a response to evolving upstream developments. The growth in North American oil production is best understood through a discussion of the shifts in terms of volume, location and quality.

Not only has production grown in terms of a rapid increase in volume, but the geological potential for tight oil in particular exists in many parts of the continent and new production is coming from both traditional and non-traditional production centers. Moreover, much of the tight oil production in the United States is light density oil, different from the heavier quality crude that was previously expected to be a growing share of North American production.

The quality of new production has important implications for the economics of production and refining, as well as North American crude oil import trends. Combined, these three supply changes – volume, location and quality – have reoriented North American crude flows.

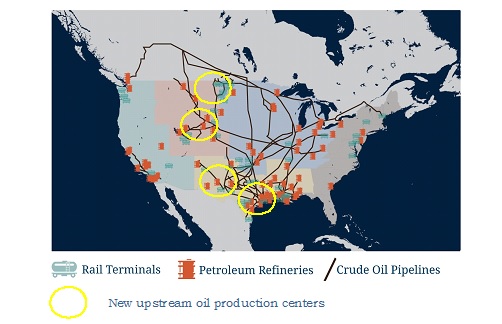

Traditionally, North American crude flows fell into four major groups: Gulf Coast to Midwest, Intra-Gulf Coast, Gulf Coast to East Coast and Intra-West Coast. As these flows were relatively fixed and stable, producers and consumers invested in pipelines and facilities to move large volumes of crude along these routes and import crude from abroad.

Three upstream changes have upended some of these established crude and product flows. As a result, there are now fewer imports from outside North America and changing flows, including new flows from the Midwest, South, East, and to a lesser extent the West. These changes have happened in a relatively short period of time and have created incentive for moving a greater share of oil by train and barge (Figure 2).

It was not just a lack of takeaway capacity and congestion in the pipeline system that enabled the spectacular growth in alternative modalities to transport crude over the last few years. The rapid growth in these modes is also attributable to flexibility enabled by a multimodal network that allowed producers to move crude to market with flexibility of destination, time commitment and volume.

Pipelines are still far and away the predominant mode of crude oil transportation, and are likely to remain so. However, whether these direction and modality changes – and the relative share of oil moving by pipelines – are temporary or permanent is an open question and depends on a range of dynamic factors in the market.

The changes are prompting debates about a specific set of energy policy and regulatory issues. We have identified five core areas of regulation and policymaking that are affected by the changing oil infrastructure, which requires attention from policymakers.

The report does not attempt to resolve these policy issues, but instead presents a balanced way the various elements of each issue should be considered. In doing so, it suggests the time is right to undertake a broad strategic review of each issue in light of the dynamic energy landscape.

The chief issues are:

Transportation safety – Nowhere has the struggle for industry and regulators to keep pace with change been more acute than with respect to crude oil transported by rail through which the transportation of huge volumes of crude oil traveling has led to an increase in spills and several high-profile accidents, resulting in raised public awareness and concern.

The nature of these concerns and the public demand for appropriate action require a swift and thorough response. This response to safety concerns is well underway, but as recent accidents continue to demonstrate, constant vigilance and cooperation among industry and regulators is necessary to ensure safe delivery of crude by rail.

Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) – The North American production surge and its impact on midstream infrastructure raise an immediate issue regarding the SPR – whether the dramatic shifts in infrastructure limit the ability to move the SPR oil resources as intended.

But the question of whether the SPR is able to optimally function in a time of disruption triggers another: Is upgrading the logistical system vital to the SPR’s functioning worth the cost, and if so, what should these stockpiles be comprised of, where should they be located, and who should own them?

Addressing the structure of the SPR would require reconsidering its purpose in a world in which U.S. consumption is declining and production is increasing. These are questions that are beginning to be explored in light of the new changes.

Crude oil exports: The increased volume of U.S. tight oil production has affected the economics of oil production and use throughout the value chain in North America. Rapid increases in production, infrastructure constraints and changing market conditions have created complex commercial dynamics for market participants seeking the highest return on investment.

The practical result has been a rapid rise in U.S. exports of both crude and petroleum products and a decline in imports. Despite growing volumes of crude oil exports to Canada, there are significant legal and regulatory barriers to unrestricted exports of crude oil from the United States (no such restrictions exist on petroleum products), which upstream oil producers would like revisited.

The question in front of policymakers is whether the restrictions on crude oil exports should be modified, and if so, how? The debate thus far has centered on the potential distribution of costs and benefits resulting from the removal or continuation of current policy. While the quantifiable economic impacts have been studied by a variety of groups, the barriers to action are political as well as economic. A review of export policy in light of its resilience to various market conditions and strategic priorities over time is warranted.

The Jones Act: The rising volume and changing location of domestic production has increased the importance of moving oil in and around U.S. domestic waterways. One complicating factor in these waterborne domestic trade flows is section 27 of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, more commonly referred to as the Jones Act.

The Jones Act stipulates that cargo being shipped between U.S. ports can only be carried by U.S.-built, flagged and owned ships. As such, the cost of shipping between U.S. ports is more expensive due to higher building, maintenance and labor costs. On some occasions, lack of Jones Act-compliant vessels has made shipping difficult.

While promoting a robust merchant marine may be in the U.S. national security interest, doing so comes at a cost. As production increases and the United States increases its reliance on waterborne transportation of crude oil, the Jones Act is another place where policymakers may want to assess strategic value and weigh it against the commercial impacts of that policy.

Climate Change: Concerns have been raised about the role midstream infrastructure expansion would have on climate change. Climate scientists may disagree about the duration and proximity of the window of opportunity for action, but most believe substantial action must be taken in the near term to prevent the most harmful impacts of climate change.

What is less clear is the role that incremental North American oil production plays in the broader climate problem. It would be ideal if the United States undertook a strategic review to consider the costs and benefits of a climate policy, and assess how unconventional oil production fits in, but it seems unlikely that a reconciliation of viewpoints on this divisive issue is possible at this stage.

U.S. policymakers are unlikely to resolve these core tensions in the near term. In the interim, the energy system is robust and operational, so the investment environment should be kept as clear as possible by providing long-term policies on emissions.

Ultimately, the scope and pace of future oil production growth in North America will be determined by many factors, including geology, access to resources, the pace of technological innovation, the global opportunity pool, commodity prices, demand growth, and social and environmental costs.

The challenge before policymakers is to ensure midstream policies are robust enough to accommodate a variety of possible future scenarios while simultaneously balancing economic efficiency, environmental sustainability and energy security.

Authors: Sarah Ladislaw is director and senior fellow in the CSIS Energy and National Security Program, where she concentrates on energy market trends, geopolitics, energy security, energy policy issues, and climate change. She received her bachelor’s degree in international affairs/East Asian studies and Japanese from the George Washington University in 2001 and her master’s degree in international affairs/international security from the George Washington University in 2003.

Frank Verrastro is senior vice president and the James R. Schlesinger Chair for Energy & Geopolitics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Verrastro holds a B.S. in biology/chemistry from Fairfield University, a master’s degree from Harvard University, and he completed the executive management program at the Yale University Graduate School of Business and Management.

Michelle Melton is a research associate with the Energy and National Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). She provides research and analysis on a wide range of projects associated with domestic and global energy trends, including the global oil market, unconventional fuels, U.S. energy policy, Iraq, U.S. electricity markets, and global climate change issues. Melton received masters’ degrees in foreign service and international history from Georgetown University.

Lisa Hyland is associate director for the CSIS Energy and National Security Program, where she provides analysis on a range of domestic and global energy trends, particularly natural gas, emerging technologies, and the Asia-Pacific region. She holds a bachelor’s degree in political science and history from Creighton University.

Kevin Book heads the research team at Washington, DC-based ClearView Energy Partners, LLC, an independent firm providing U.S. and international energy policy insights to institutional investors and corporate strategists. He holds a master’s degree in law and diplomacy from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and a bachelor’s degree in economics from Tufts University.

[inline:CSSI_report2 (2).jpg]

Pipelines still dominate the midstream, but other transport modes now play a larger role. Source: EIA, CSIS

Comments