July 2017, Vol. 244, No. 7

Features

Permian Basin: How Long Can It Grow in Low-Price, Oversupplied Market

Coming out of the first quarter in 2017, the venerable Permian Basin had no fewer than three major natural gas takeaway pipeline projects on the drawing board along with several liquid pipe projects as well, exuding an industry-leading appeal among the U.S. major oil and gas production basins.

The prospective projects all promised to ease a looming production glut in the Permian producing region, linking to existing pipelines, including those that export gas to Mexico and to a Cheniere Energy Inc. liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facility under construction.

Amidst the buildout, Dallas-based EnLink Midstream completed 150 miles of high- and low-pressure crude gathering pipelines with 100,000-bpd capacity and was expanding its natural gas and natural gas liquids (NGL) footprint in the heart of the Permian. Meanwhile, well-endowed private equity funds managed by Blackstone Energy Partners and Blackstone Capital Partners scooped up the Permian’s largest privately held midstream operator for $2 billion in cash.

From just these industry headlines, it’s easy to get the impression the Permian is the latest bandwagon, and a lot of newcomers are jumping aboard, joining longer term players like EnLink, which entered the Permian in 2012 and has grown its presence there over the past two years. And the proof is overwhelming when it is recognized that just about every major financial and energy industry publication has done a report in recent months touting the dominance of the Permian.

On the ground, this translates into heightened planning and building infrastructure expansions. Since the Permian is an old veteran in the U.S. oil and gas wars dating to the early 20th century, pipeline infrastructure already is plentiful, but it’s going to get more so if the continuing market enthusiasm is an accurate indicator of future development. Industry veterans ponder how long all this growth can last, along with the usual skeptical questions needed to keep all the elevated hype in perspective. There are always skeptics as advocates like Stephen Robertson, executive vice president of the Permian Basin Petroleum Association (PBPA), knows all too well.

Given the still relatively low global commodity prices and oversupplied world markets, can the Permian maintain its attractiveness to investors and exploration/production (E&P) companies? What are the prospects for continued rig growth? Is the Permian impermeable to various global headwinds? How do operators deal with the stark differences between the New Mexico and Texas portions of the basin?

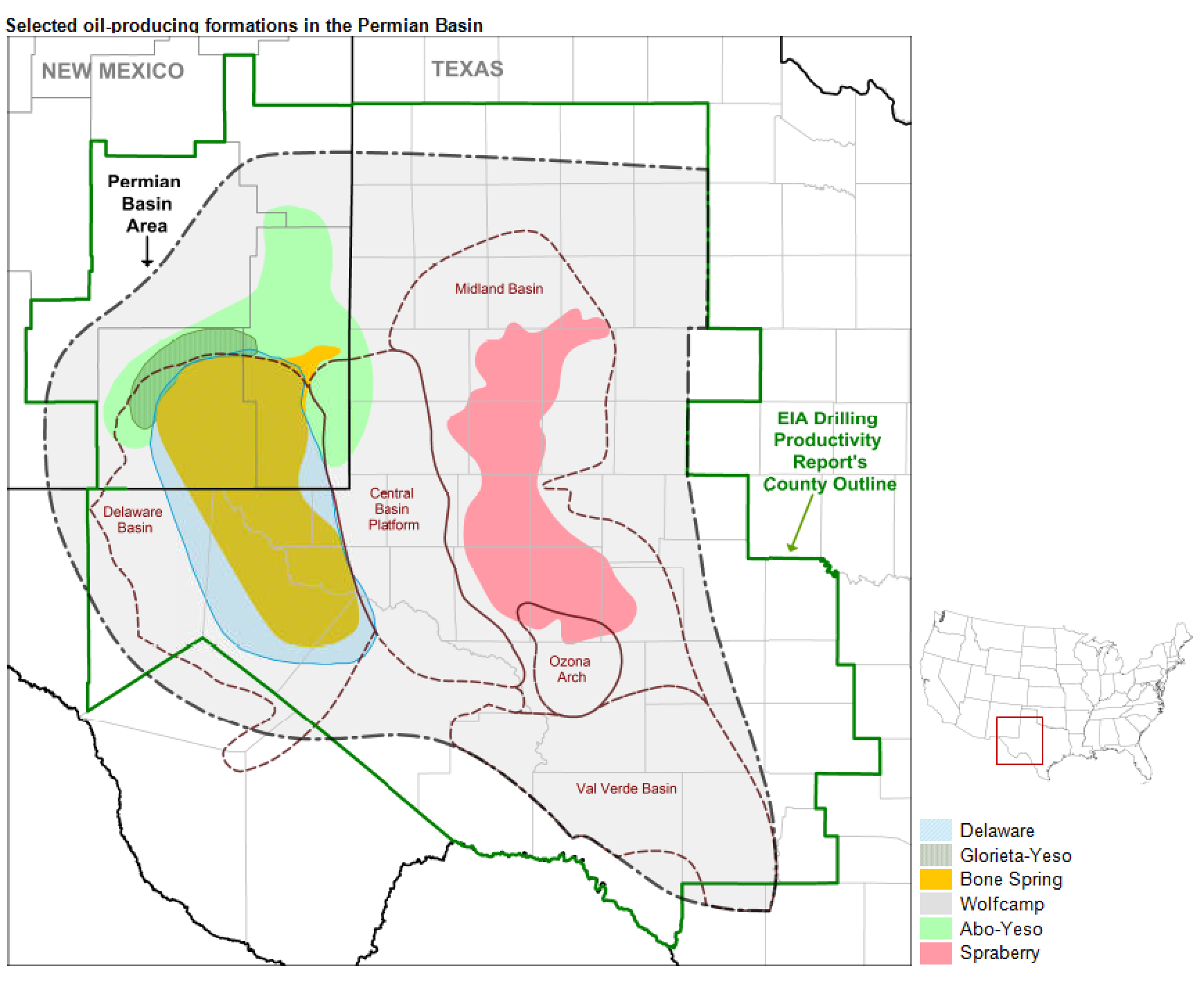

Geology, rather than state lines, marks the Permian, according to some of the experts P&GJ contacted. Differences in the Permian are better split between the Midland sub-basin that is entirely in Texas and the Delaware sub-basin that runs across both states. “However, both of these sub-basins provide stacked play potential, and both are supported by educated and experienced work forces,” said PBPA’s Robertson.

For a large part of the basin’s geologic history, the area included a shallow inland sea where many flora and fauna lived and perished. There are multiple rock formations or benches in which hydrocarbons are trapped. As a result, Permian conversations are peppered with references to the “Yates, San Andres, Clear Fork, Spraberry, Wolfcamp, Yeso, Bone Springs, Morrow and Devonian.” Even better, many of these formations are lying stacked on one another underground.

Robertson knows most other U.S.-producing basins, including the Eagle Ford and Barnett shales in Texas, are limited to one or only a few formations from which to produce hydrocarbons. In the Permian there is the chance to significantly increase the amount of hydrocarbons that can be produced in one location because of the ability to use what he calls “horizontal kick outs from a single vertical location.”

“Because of the multiple formations from which production can occur, operators in the Permian are able to reduce drilling costs while increasing production without having to drill separate vertical locations to increase producible acreage,” Robertson said.

With both high returns and high growth offered, investment professionals like Mike Kelly, managing director and senior analyst at Seaport Global Securities LLC, told energy observer Luke Geiver in April that he estimates eight of the top 10 oil and gas companies tracked by his firm have ties to the Permian. Kelly thinks investors are right to feel bullish about the prospects in West Texas and southeastern New Mexico.

Among the primary reasons for the investor stampede are the multi-zones and significantly higher per-well production in comparison to other major plays in North America. While the resulting high prices for acreage in the first four months of 2017 may seem excessive, analysts like Kelly suggest that in the future these prices may turn out to be relative bargains. These same analysts also remind listeners that the Permian developments must be analyzed within the global context and how worldwide price and supply/demand developments might affect the basin’s future.

Noting that his midstream company considers the Permian a core growth area, Steve Hoppe, executive vice president and head of EnLink Midstream’s gas business unit, praised the Permian as a basin that “can be profitable in constrained markets due to the high quality of the reservoir and its low break-even prices to develop the resource.” Even with the inevitable swings in global commodity prices, Hoppe sees “advances in drilling and completion efficiency continuing to support volume growth in the Permian, even in the lowest price scenarios.”

EnLink has intentionally positioned itself squarely in the Permian because “it could support consistent long-term growth,” Hoppe said.

The bottom line on the Permian is there are few, if any, global scenarios short of a complete price collapse worse than what was experienced in late 2014-15 that can change the attractiveness of West Texas. The STACK in Oklahoma is extremely prolific and a competitor, but it is much smaller. In addition, four major companies (Marathon Petroleum, Devon, Continental Resources and Newfield Exploration) essentially have all of STACK’s productive acreage locked up. In the Permian, in contrast, there is still a lot of room for new companies and for acreage acquisition, which has been unfolding aggressively since mid-2016.

“I think we will see continued production growth in the Permian,” said Amol Joshi, vice president and senior analyst at Moody’s Investors Service. “One reason is that many companies have bought a lot of acreage which they need to put to good use and start producing oil and gas.”

Citing ExxonMobil’s $6.6 billion purchase at the outset of 2017 to more than double its Permian Basin resource ownership and add about 275,000 acres total, mostly in New Mexico, Joshi noted the transaction with the legendary Bass family of Fort Worth added an estimated resource of 3.4 Bboe in New Mexico’s Delaware sub-basin, and ExxonMobil ended up with about 6 Bboe of resource total in the Permian.

The New Mexico portion of the Permian has begun to create its own buzz in recent years, and analysts vary in how they differentiate between the two. Generally, New Mexico is a bit more gassy, so the economics aren’t as strong, said some experts. Others will point to “infrastructure challenges” in New Mexico.

“I know there is a lot of scatter-shot acreage on the New Mexico side, so there needs to be more acreage consolidations through swaps and sales,” Joshi said.

While it is the more remote part of the Permian with less infrastructure development and more federally managed lands, EnLink’s Hoppe said his company “has had success in establishing a presence in New Mexico and looks forward to expanding its business in the state.”

Permian association’s Robertson said comparison of the Permian in each state inevitably requires looking at each state’s respective regulatory environment, and he thinks New Mexico is easily the less favorable one.

“The regulatory environment in New Mexico constricts growth of the oil and gas industry, and with opportunities in the same basin in a neighboring state, many companies might base their operating location on this fact alone,” Robertson said. “The growth of the New Mexico portion of the Permian will always be tied to the burdens of the regulatory environment.”

This sub-regional reality, however, does not seem to taint the overall Permian reputation. The Texas portion, particularly in early 2017, had more rigs operating than in all of the other major producing basins in the United States combined. The two highest U.S. rig counts by county are found in the Texas portion.

“One reason all of these companies like to be in the Permian is that they are rewarded by investors,” Joshi said. “When a company said it is in the Permian, they do tend to be rewarded by investors lately, although I don’t know how long that will continue. Acreage prices have been going through the roof in recent quarters.”

For analysts such as Joshi, the risks and rewards of the Permian relative to other plays are factors, but not really important in the 2017 global energy landscape. There are no easy comparisons for the Permian with, say, the Marcellus, Utica or the SCOOP, all of which are more “gassy.” Takeaway infrastructure constraints in Marcellus/Utica are real now, although eventually they are expected to be resolved. The competing plays closer to the Gulf Coast also are of interest to Joshi.

“We’ll see how they work out [relatively], but at least they don’t have the transportation constraints or costs of the Marcellus and Utica,” he said.

In the Utica and Marcellus, average wells are highly productive, so that helps the economics despite the added transportation costs, and in the SCOOP, it is a gassy play, too. The STACK, Permian and Bakken are the oilier ones, and the Bakken is prolific in the core, but there isn’t as much geologic formation diversity as in the Permian.

The Permian’s relative advantages and its “edge,” so to speak, is also part of the risk side of the equation because with its high profile comes greater attention from the environmental sector, particularly the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) that has re-doubled its methane emission reduction campaign in the wake of the Trump administration coming to power.

On its Energy Exchange blog in April, EDF’s Jon Goldstein and Ben Ratner took aim at the Permian with recognition that ExxonMobil and other majors are committing billions of dollars to the play, raising the question for them of whether the new large investments will come with equally large investments in technology to limit methane emissions.

“It’s not just an academic question,” the EDF pair noted. “The answer will go a long way toward revealing if industry actors plan to operate in a way that serves the best interest of local communities and taxpayers,” while also alleging that New Mexico [where a large portion of ExxonMobil’s investment is aimed] is “currently the worst in the nation for waste of natural gas resources.”

More broadly, from a global perspective, it is unclear the Permian can ever have the overall impact some of its more ardent boosters predict. Experienced industry observers tend to emphasize all of the enthusiasm in the oil patch but say Wall Street has overstated the Permian’s realistic future impact on fundamentals such as global oil prices.

Dave Yager, a former oilfield services executive, wrote in April that while the Permian “is a wonderful and significant mass of hydrocarbon-rich formations,” it is not a game-changer on a worldwide scale. He differentiates sharply the basin’s U.S. vs. global influence with the former being where the impact really shows.

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates in spring 2017, for example, showed the United States exiting the year with record production of 9.64 MMbpd, slightly higher than its 2015 peak of 9.61 MMbpd. Analysts like Yager see this as nearly 400,000 bpd more than the 9.235 MMbpd the EIA reported in early April. Domestically, the Permian is definitely moving the metrics.

Part of the Permian success is a reflection of what has happened in the North American oil patch overall. Namely, technology has finally taken hold in the onshore oil and gas sector after years in which it was only offshore where that was the case. Bloomberg and other business news outlets recognize that onshore operators are no longer reluctant to embrace high-tech. In part, the global oil commodity price crash in mid-2014 has accelerated the transition that now includes sophisticated DNA sequencing to track crude in buried pipelines and robots for fitting the pipe segment together.

At the end of 2016, Schlumberger’s president for operations, Patrick Schorn, noted his company’s oilfield service technology offerings had doubled over the past two decades. Citing the Tulsa-based oilfield market research firm Spears & Associates, Schorn noted Schlumberger’s technology portfolio has a position in 25 of the Spears-designated oilfield service markets; 20 years ago that would have been 11 markets. It offers 19 technology product lines split among four groups. “Twenty years ago, we had only seven product lines,” Schorn told his audience at the Cowen & Company Energy Resources Conference.

By the end of 2017, Schlumberger executives are expecting all of their previously idled oilfield services equipment to be back in action with all of their E&P clients being in a ramp-up mode. They estimate 2017 oilfield spending would jump by 50% compared to 2016. Permian projects were already bearing fruit by the second quarter.

Schlumberger’s WesternGeco completed acquisition of a 3-D wide-azimuth, multi-client survey covering 253 square miles in the southern part of the Permian, bringing total coverage there to 655 square miles. The industry-supported project is expected to provide data to help operators improve drilling and completions efficiencies.

Similarly, Schlumberger’s drilling and measurements unit used a combination of technologies to increase drilling performance in long well laterals for Parsley Energy Inc. in the Midland and Delaware sub-basins. In drilling 80 wells over a recent 12-month period, Schlumberger technology contributed to the 17% reduction in the average days required to drill a well compared with the previous year. Parsley was able to reduce average total drilling cost per lateral foot by 30%, according to Schlumberger.

In the first quarter, EnLink completed its Greater Chickadee crude oil gathering system linked to several major market outlets and key hubs in the Midland area. It also joins the company’s established gas gathering and 400 MMcf/d processing system in the Midland Basin, Hoppe pointed out. Through a partnership with Natural Gas Partners in the Delaware Basin, EnLink is expanding its Lobo II processing facility that promises to add 185 MMcf/d of processing capacity by the end of 2017.

The technological advances that companies like EnLink, Schlumberger and many assorted operators are bringing are not unique to the Permian, but their economic multipliers can have a greater impact because of the other advantages the basin offers, starting with its size and diversity. In square miles, the Permian is equivalent in size to the entire state of Alabama.

Along with size, spreading over West Texas and southeastern New Mexico, the Permian’s various attractions remain more varied than other U.S. basins, including the legacy infrastructure, experienced local workforce, deeply developed stakeholder relations, all supported by excellent geologic aspects and its stacked play. This combination promises to keep would-be investors interested where over the end of 2016 and the first quarter of 2017, a significant amount of new investment was brought in, according to the PBPA’s Robertson.

“If the price of WTI remains steady, growth here will continue,” said Robertson, noting the Permian is not exempt from the pricing and supply/demand headwinds that buffet the industry in a regular boom-bust cycle. “Slight changes to WTI, because of the investment already made, might not affect operations too much, but if the commodity price changes drastically, it’s a completely different story. Operations in the Permian are still very reliant on strong commodity prices; however, because of other benefits the Permian offers, we might be able to take some of the hits that other basins can’t.”

In 2017, another aspect of this attractiveness for the Permian was stretching to the always supply-hungry refining and export operations on the Texas portion of the Gulf of Mexico. Suddenly there was more of an allure between West Texas and the Corpus Christi area on the Gulf Coast.

Morningstar’s Sandy Fielden calls Corpus Christi the “new Permian window on the world” in an industry essay he wrote this spring on how the Gulf port is the focus of significant new investment in crude pipelines and marine export terminals. It is all aimed at getting Permian and Eagle Ford supplies to the refineries and so-called splitters in Corpus Christi, not to mention the export terminals.

After a sudden lull in 2015 following the commodity price crash, the southern Texas Gulf port is “back in the spotlight,” according to Fielden.

“Expanding Permian production has prompted at least two new pipeline projects to deliver crude from the Permian to Corpus Christi,” he wrote in his analysis that counted 11 crude terminals operating or planned in the port. “If permitted and built on schedule, they would add another 1 MMbpd of capacity into [the Gulf port] by the end of 2019.”

A caveat about global demand for U.S. crude exports that Fielden offers regarding Corpus Christi’s “overbuilt” status is worth keeping in mind when considering the Permian production region. Without increased global demand for the U.S. supplies “an oversupplied market could prompt lower prices that might in turn choke off new shale production,” he warns, calling it part of the quandary for midstream developers today in what he dubs as a “post-shale world with shorter boom-bust cycles.”

The continuing global environment of oversupply and low commodity prices is exactly why there is so much activity ongoing in the Permian because as oil and gas basins go, “it is highly economic,” Moody’s Joshi said. “It varies with each company, but generally speaking, it is highly economic.”

Companies are consolidating their acreage positions with various swaps and sales, he said, as another example that this is a hot area in the U.S. oil and gas landscape. There are also longer and longer laterals being completed through hydraulic fracturing jobs in the Permian.

Some of the issues potentially affecting longer-term development in the Permian are what all the U.S. shale plays now face: (a) how much efficiency gains can be continued; (b) whether sufficient takeaway capacity can keep up with production growth; and (c) how much service company and fracking costs will rise.

Robertson cautions that if infrastructure cannot keep up with production, “one of the benefits of the Permian will be weakened.” On the other hand, he noted, “the stacked play prospects in the Permian aren’t going away anytime soon, giving the basin a benefit not found in many other producing basins around the world.”

The economics are influenced by the Permian’s stacking; ideally investors want producers with economies of scale provided by multiple stacked drilling opportunities of prolific wells, according to Joshi.

“You don’t see that in the Eagle Ford and the Bakken to the same extent,” Joshi said. “For the Bakken, you also have the issue of higher transportation costs, which you don’t have yet in the Permian.”

“When you look at all the issues [economics, drilling opportunities, infrastructure, transportation costs, etc.], you can see that the Permian is a pretty nice place to be,” Joshi said. “The challenge facing these companies is that many of them paid a lot for their latest acquisitions, and on a full-cycle basis when you consider all-in costs of the acquisition and subsequent development, whether it turns out as economically beneficial as other plays in which you could buy in cheaper is anyone’s guess.”

Richard Nemec is P&GJ correspondent in Los Angeles. He can be reached at rnemec@ca.rr.com.

Comments