December 2019, Vol. 246, No. 12

Features

Europe’s Gas Distribution in Need of Evolution

By Nicholas Newman, Contributing Editor

Europe is in transition toward a low-carbon economy in which fossil fuels’ share of the energy mix is projected to fall from nearly 75% in 2017 to 59% in 2040, according to BP’s latest Energy Outlook, due mainly to declining coal power generation in many countries.

In the short term, the decline in North Sea’s gas output, phasing out of coal and nuclear power plants and the increasing use of gas-peaking plants, should increase the demand for natural gas by 20 Bcm, which is enough to satisfy one-third of Europe’s market need in 2025.

However, by mid-century, improved energy efficiency measures by industry, buildings and transport, growth in renewables combined with energy storage, should see a 2% reduction in the share of natural gas in the power sector.

Nevertheless, according to IEA forecasts, European imports of 195 Bcm of natural gas today are set to rise by a significant 71 Bcm between 2018 and 2040. This will mean that Europe’s distribution network capacity will have to be improved, especially during peak winter demand in the northern hemisphere.

Europe currently enjoys a diversity of suppliers. Pipeline gas is received from Central Asia, Russia and North Africa. More expensive LNG imports, though currently relatively low and relatively expensive, arrive by tanker from the Eastern Mediterranean, Russia, West Africa and, more recently, from North America.

Russia is, however, Europe’s main supplier of gas and is likely to remain dominant until at least 2040, when it is forecast to supply one third of the EU’s gas needs, according to the 2019 IEA World Economic Outlook. LNG imports will grow in coming decades as new suppliers come on line in North America, Latin America and Africa.

In 2018, European Union countries imported 401 Bcm of natural gas of which about 39% came from Russia. Heavy dependence on Russian gas has brought security of supply to the fore, not only from the U.S., looking for new markets for its LNG exports, but also from Poland and the Ukraine, faced with the loss of transit fees for transporting Russian gas across their territories.

For economic and political reasons, Russia’s dominance is heavily scrutinized but, what is often ignored, is that the dependence is symbiotic. Europe is a major source of profit for Russia’s Gazprom and it is, therefore, in the company’s interest to serve this valuable market reliably.

The gas distribution system also is often overlooked in the context of energy security. Europe needs the right capacity of pipelines, in the right place and in the right direction to carry gas to market. In practice, the following criteria underpin Europe’s energy security:

- How easy is it for gas to be transmitted from one country or region to another?

- How patterns of demand might change?

- What role gas infrastructure might play in a decarbonizing European energy system?

Distribution

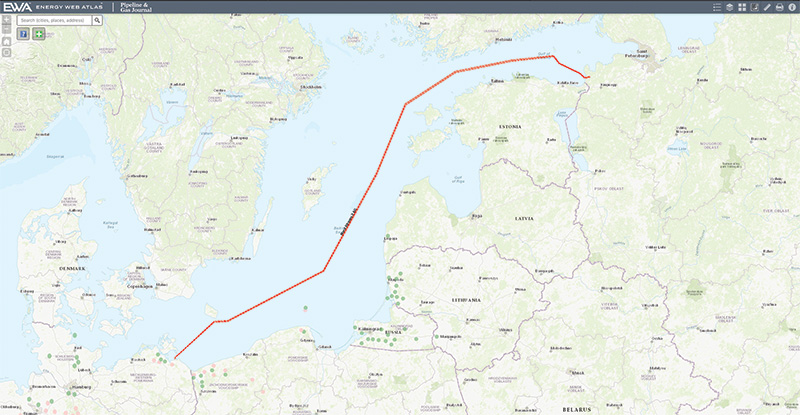

In 2018, Europe’s gas consumption stood at 18,168 thousand Tera joules, according to IEA figures. The completion of the contentious Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project should further improve Russian gas export capacity to Germany and the rest of Northern and Western Europe, making it more difficult for LNG exporters in the Americas to compete with cheap Russian gas.

In contrast, central Europe and the Balkans have only limited access to gas. This will change with the completion of the Trans Adriatic Pipeline bringing gas from Azerbaijan via Turkey to Greece, Bulgaria, Albania and Italy.

Furthermore, supply opportunities will be further enhanced by the ongoing development of LNG import facilities and new offtake pipelines in Greece and Croatia. These developments should reduce fears of energy security in what are, up to now, gas deficient markets in central and southern Europe and the Balkans.

Security vs. Demand

In the northern hemisphere, gas consumption for heating and power generation doubles during the six months of winter and recedes in the summer months of April to September, during which time the existing gas distribution network and storage facilities are under-used. Therefore, assuring supplies in winter becomes a security issue.

Europe’s gas markets are changing because of evolving policy, electrification of heat and transportation and the increased market penetration of renewables facilitated by new gas- peaking power plants.

Energy efficiency measures are set to intensify. Starting in 2021, the EU has raised the annual energy efficiency standards to 2% for the building stock. This is expected to lead to a 25% decline in peak monthly gas demand and yield savings of almost €180 billion in the EU’s gas import bill for 2017-2040.

Electrification will boost power generation from 42% in 2017 to 52% of total primary energy consumption by 2040. Electrification will boost the share of renewables in the power sector by almost 170%, facilitated by the availability of gas-peaking plants for fast back-up power and large-scale energy storage facilities.

At the same time, electrification of heating, power and transport is set to increase. For example, Norway plans to end the sale of petrol and diesel cars by 2025. Others, including Germany, Holland and France have set a target of 2040, reports BBC News in October 2018.

In Europe, the share of plug-in electric vehicles will rise from roughly 2% of new sales in 2017 to around 9%, or 1.5 million vehicles, by the middle of the next decade, according to JP Morgan. As for the industrial sector, monthly peak demand for gas is expected to decline by almost a third by 2040 thanks to improvements in energy efficiency.

To sum up, under the IEAs New Policies Scenario, changes in the pattern of gas demand, most notably a 50% increase in monthly peak gas demand from the use of back-up power, require a rise in gas imports but do not prevent an overall decline of 2% in the use of natural gas for power generation by the mid-century.

However, many industry insiders suggest that the IEA’s demand forecast is too optimistic, since it ignores improvements in demand management, advances in energy efficiency technologies and the increasing competitiveness and productivity of energy storage in meeting back-up power.

A scenario in which there is an actual decline in gas demand would undoubtedly have a negative impact on the providers of gas distribution and storage services. Europe, therefore, needs to formulate policies that ensure that natural gas distribution and storage has a future.

Concerns about Europe’s energy security have focused on the continent’s sources of gas supply and how gas is delivered to customers. However, the transition to a low-carbon economy raises thorny, as-yet unanswered questions for decision-makers:

- What is the role of gas under growing electrification of heating for buildings and transportation?

- What is the future role of Europe’s gas pipeline distribution network?

- Could natural gas be replaced by green gases such as hydrogen and bio-methane?

- How will changes in the market environment impact on safety of the gas distribution networks of Europe?

While Europe’s gas infrastructure is a valuable asset, like many other pieces of energy infrastructure, it will need to evolve and adapt to the demands of sustainable development. P&GJ

Comments