November 2022, Vol. 249, No. 11

Features

Carbon Capture Not Ending Pipeline Woes

By Jeff Awalt, P&GJ Executive Editor

(P&GJ) — With growing demand and government incentives to develop more carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) capacity, some of the biggest U.S. pipeline projects now on the drawing board are designed to transport CO2 from source to storage.

But the road to energy transition is proving to be a bumpy one, as some proposed pipelines that could help address climate change by reducing carbon emissions face similar opposition to those that transport oil and natural gas.

Three projects in the Midwestern farming belt may serve as leading indicators of the ability to economically construct major CO2 pipelines: Midwest Carbon Express, Heartland Greenway and the ADM/Wolf Carbon Solutions project.

Proposed to cross six states, the pipelines – totaling 3,650 miles of new construction – would transport carbon dioxide captured mainly from the emissions of ethanol plants before being stored deep underground in Illinois and North Dakota.

Unlike other CO2 projects under development in the West Texas Permian Basin and Louisiana Haynesville oil and gas production areas, the Midwestern projects are associated with ethanol production and cross areas of farmland owned by people who are less experienced with pipeline operations or confident in their safety. The dynamics have made it easier for opponents to spread fears about contamination risks and raise landowner hackles over issues of eminent domain.

In Iowa, some farmers along the proposed pipeline routes have refused to allow surveyors on their property despite a state law requiring them to permit access. Among those are a couple from Moville, Iowa, who twice denied access to their land, forcing Heartland Greenway’s developer to request an injunction against them. The couple later filed a counterclaim challenging the constitutionality of the Iowa law that permits surveyor access to private land.

The issue has captured the attention of regional news media that have mostly stuck with the tried-and-true David vs. Goliath angle of landowner against corporation, a narrative that industry insiders say is pushed by attorneys and advocacy groups.

Competing op-eds and letters to the editor have appeared in newspapers such as the Des Moines Register. A letter titled “CO2 pipeline technology is safe and beneficial” was contributed by the president of a local Laborers International Union in response to a submitted piece titled, “We’ve done the research, and we oppose the proposed CO2 pipelines.”

Those opponents contend that a buried pipeline would result in soil degradation and reduced crop yields. Environmental justice advocates, meanwhile, are rallying around the message that CCS will prolong the energy transition and allow industries to continue polluting underprivileged communities, while ignoring the resulting decline in pollution in those communities and the absence of sufficient alternatives. Non-profit environmental groups, whose fundraising is fueled by demonization of industry, argue that CCS projects don’t net enough carbon reduction to be worthwhile.

But it is the eminent domain issue that appears to resonate most in the Don’t-Tread-On-Me era with some Midwestern farmers. Developers are hopeful those opposing and undecided landowners during the early project stages will recognize their benefits and ability to operate safety as they become more familiar with the projects through ongoing dialogue.

“I know just from growing up in this area on a family farm myself that pipelines can be a divisive piece of infrastructure regardless of what’s going through them, and infrastructure today is just difficult to build,” Elizabeth Burns-Thompson, vice president of Government and Public Affairs at Navigator CO2 Ventures, told P&GJ. “Also, you layer on top of that, that carbon is still effectively a new commodity for many.”

Unlike liquid fuels and natural gas, for example, carbon dioxide is less understood among people who may fill their cars with gasoline and cook with natural gas, making public engagement and education especially important for CO2 projects.

“Naturally, there is a bit more of a learning curve when you’re talking about something that folks don’t handle on a day-to-day basis,” Burns-Thompson said, noting that carbon has been thrust into the limelight in agricultural circles in a way that may feel too fast for some when it arrives at their property line.

“It’s important when going into local presentations or webinars or town halls not to lose sight of the fact that, for nearly everyone coming into those venues, this is the first time they’re hearing about carbon capture,” she said.

The suggestion that CO2 pipeline developers are rushing to take land via eminent domain couldn’t be farther from the truth, Burns-Thompson said, emphasizing that project opponents have wrongly presented it as a kind of trump card that makes things easier for the company

“The basics of condemnation just do not make business sense when you think about it in practice because, one, it doesn’t save us time; two, it doesn’t save us money; and thirdly, it doesn’t make us any friends,” she said.

“Anyone in any business would say optimization of your resources, be it time or money, is critical to having a sustainable business, and generally you want customers to have a good feeling about you,” Burns-Thompson added. “It is truly a tool of last resort. So, the way it is being portrayed to the public is a strong mischaracterization, and we are out there trying to proactively right that.”

Even as they face legal skirmishes from some opponents, CCS projects have drawn support in the region from more like-minded environmental, agricultural and labor groups, along with those industries looking to reduce the carbon intensity of their operations via CCS.

In Iowa, the heart of the America’s Heartland, about 60% of the state’s corn crop is consumed by ethanol production. Many proponents of CCS projects there recognize that the future of ethanol production will be determined, at least in part, by refiners’ ability to reduce CO2 emissions into the atmosphere.

ADM-Wolf Carbon

One of them – Chicago-based food processing and commodities giant The Archer-Daniels-Midland Company (ADM) – is partnering on a CCS project in Iowa and Illinois with Wolf Carbon Solutions, an affiliate of $4 billion energy infrastructure company Wolf Midstream of Calgary, Alberta.

The centerpiece of the project will be a new 350-mile steel trunk line. The pipeline will offer dedicated capacity to transport CO2 from ADM’s ethanol and cogeneration facilities in Clinton and Cedar Rapids, Iowa, to be stored permanently underground at ADM’s fully permitted and already-operational sequestration site in Decatur, Illinois.

The pipeline would be capable of transporting 12 million tons of CO2 per year with significant spare capacity to serve other third-party customers looking to decarbonize across the Midwest and Ohio River Valley, its developers said.

“Customers are increasingly turning to us to help them meet their Scope 3 emissions commitments with low carbon-intensity sustainable solutions,” Chris Cuddy, president of Carbohydrate Solutions at ADM, said in a statement.

“This is an exciting opportunity for ADM to connect some of our largest processing facilities with our carbon capture capabilities, advancing our work to significantly reduce our CO2 emissions while delivering sustainable solutions for our customers,” Cuddy said.

ADM’s Decatur CCS facilities have already permanently stored more than 3.5 million metric tons of CO2 about a mile and a half deep and have paved the way for increased decarbonization of the company’s operations.

Construction of the Wolf Carbon pipeline will enable ADM to begin storing carbon emissions from its Iowa refineries at its Decatur sequestration site.

Heartland Greenway

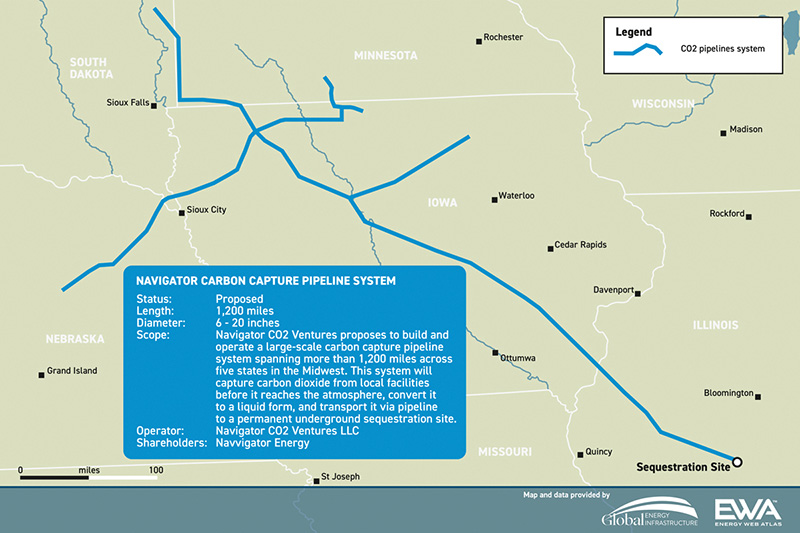

Described as “one of the first large-scale, commercially viable CCS projects to be developed in the United States,” Heartland Greenway is Navigator CO2 Ventures’ proposed system to provide biofuel producers and other industrial customers in five Midwest states with a long-term and cost-effective means to reduce their carbon footprint.

The project calls for construction of a new 1,300-mile pipeline network that will reach industrial customers in Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, and South Dakota. It would capture emissions from ADM’s facilities in Clinton County and Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and transport it for storage at its existing sequestration site in Decatur, Illinois.

In support of the sprawling project, Navigator said it will assist customers requesting such services as constructing and financing their CO2 capture equipment, transporting the captured CO2 over its newbuild network and permanently sequestering the carbon in secure, underground sites.

Initial phase commissioning is expected to begin during late 2024 and into early 2025.

At its full expanded capacity, Heartland Greenway was designed to capture and store 15 million metric tons of CO2 per year, an amount equivalent to the emissions from approximately 3.2 million cars driven annually, according to Navigator.

The project, says Burns-Thompson, brings competitive value to customers, as well as the farmers who supply them with the feedstock for their biofuels production.

“It really is the case that this infrastructure is meant to help them grow and innovate in what is becoming a more carbon-focused economy,” she said. “We want our local manufacturers to be competitive in this environment, and that means developing the necessary infrastructure.”

Midwest Carbon Express

Summit Carbon Solutions, an arm of Alden, Iowa-based Summit Agricultural Group plans to build a $4.5 billion, 2,100-mile pipeline system and CCS project, which would capture emissions from Midwest ethanol plants and transport them via pipeline across five states to an underground sequestration site in North Dakota.

“Simply put, this will be the most impactful development for the biofuels industry and Midwestern agriculture in decades,” Summit Agricultural CEO Bruce Rastetter said of the new business rollout, describing the operations as a “giant leap forward for the biofuels industry.”

With a goal of becoming operational in 2024, Summit Carbon Solutions would be the largest CCS project in the world with infrastructure capable of capturing, transporting, and permanently storing 10 million tons of carbon dioxide per year

The system is designed to reduce the carbon footprint of partner biorefineries by up to 50%, supporting their goal of delivering a net-zero-carbon fuel.

Summit Carbon Solutions announced in 2021 that it was proceeding with initial engineering, design and permitting associated with the project, which will permanently store carbon dioxide in underground salt formations.

“Summit Carbon Solutions is a truly transformational project,” Summit Ag Investors President Justin Kirchhoff said in a company announcement. “This opportunity helps satisfy the urgent global need to decarbonize and meets the ever-growing demand for low-carbon fuels by collaborating with leading biorefineries to capture and store carbon on a scale not yet achieved anywhere in the world.”

The project has faced opposition similar to others, particularly in Iowa, where Reuters in March 2022 reported that landowners have been “slow to cede their property rights” to the CO2 pipeline. While the company said it has negotiated hundreds of easements along the route, only 40 were reported in Iowa at the time. They cover 1.9% of its 703-traverse, according to a database maintained by the Office of the Iowa County Recorder.

If Summit fails to secure a route through voluntary agreements with landowners, it will resort to using eminent domain, just as opponents have emphasized.

To that point, some industry executives speak privately about not only landowners and environmental activists, but the actions of attorneys they say descend on areas of pipeline construction and stoke fears to generate business from landowners.

“It’s frustrating, because I think a lot of people are genuinely trying to do the right thing,” one Texas-based midstream CEO told P&GJ on condition of anonymity. “I think there’s some misinformation and maybe, you know, there are some quite bad actors.”

Comments