April 2024, Vol. 251, No. 4

Guest Perspective

Asbestos Pipe Abatement Possibly Simplified

By Paul D.Q. Campbell, Former Engineering Consultant

(P&GJ) — From 1914 until 1988, asbestos was just an accepted part of life and industry, and even at the end of that span, the only requirement by the EPA was the reporting of asbestos used in some products.

To this day, there is no actual generalized ban by the EPA or federal law on the use of asbestos. So, over the course of roughly seven decades in the 20th century, an estimated 600,000 milesi of asbestos concrete pipe were installed in the United States. With the passage of years, those pipes are coming to the end of their lifespan, and asbestos abatement can be hugely disruptive, extremely costly and, to a greater or lesser degree, hazardous.

What if it could simply be encapsulated in situ, entombed, at a fraction of the cost, with no disruption of services or the surrounding earth and — best of all — safely?

U.S. Patent #11,867,338, issued on Jan 9 to inventor Danny Warren in Carver, Massachusetts, says that encapsulation is a perfectly viable approach to the problem.

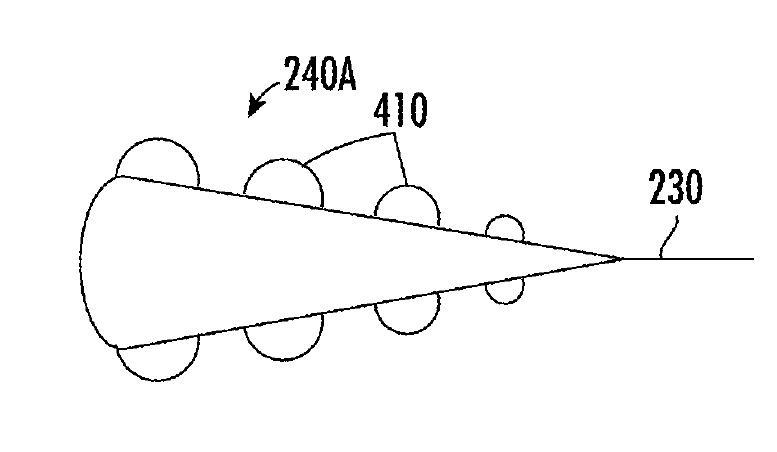

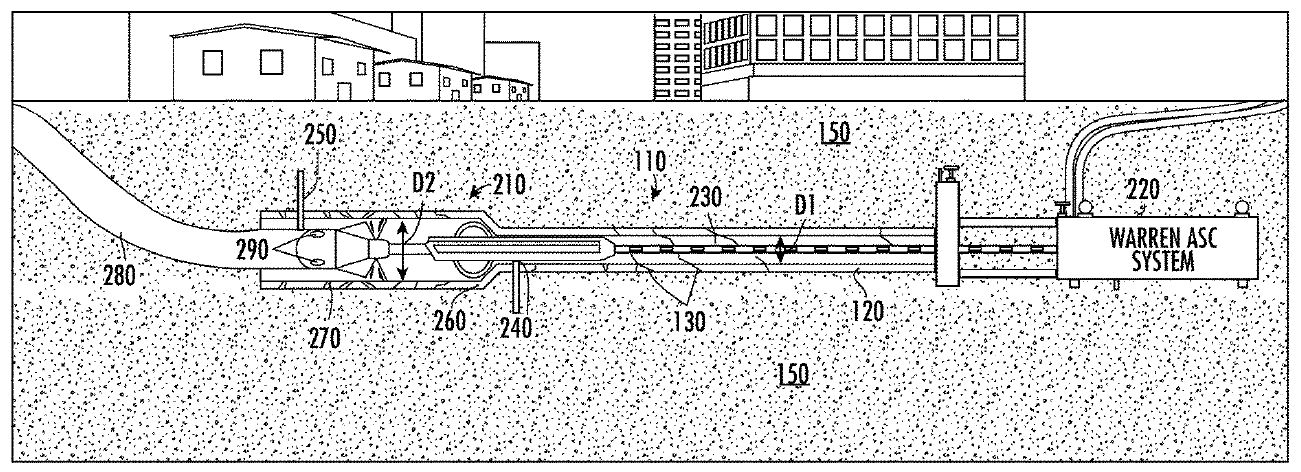

The encapsulation process is performed all at once, though this happens in three progressive steps. Initially, the existing asbestos concrete pipe needs to be bifurcated or quadrisected. A pull cable is passed down a section of the pipe to be repaired, generally from one manhole location to the next, though not always. A tapered tool with opposing cutting surfaces, referred to in the patent as a scribing head, is placed in one end of the pipe and drawn through using the cable.

There are various ways to construct the scribing head, some of which are enumerated in the patent, but the primary configuration is a series of roller-cutters, not unlike a pizza cutter wheel. These are arranged sequentially in a row with increasing diameters, so that by the time the scribing head has completely passed a point in the pipe, the wall is completely cut through.

In the second step, as soon as the pipe has been cut, an applicator is passed through the pipe that delivers 3–5 gallons per minute of reinforcement material, such as moisture-activated expanding urethane foam. The foam fills the cracks and seeps into the surrounding soil, to encapsulate the asbestos concrete pipe.

It is noteworthy that the third and final step is specified in the patent as happening “immediately” after the application of the urethane foam. This step involves drawing a high-density polyethylene (HDPE) pipe, or conceptually, a pipe-liner, into the existing asbestos concrete pipe, directly behind the applicator head.

As the urethane foam expands and ultimately “sets,” the HDPE pipe-liner is glued in place inside of the existing asbestos pipe. Any debris — either already existent from pipe degradation or due to the scribing head cutting process — is entombed in the urethane at the bottom of the pipe.

This last bit is the part of the patent that is not novel, but it was included with the intent of showing that the invention was, in fact, operable. So, at one manhole location, a launch ramp is created to allow the insertion of the HDPE pipe, and at the opposing manhole location, a winch is installed to pull the draw cable through the pipe.

The patent specifies, repeatedly, that “no dewatering is required,” saving huge expenses in the dewatering process. However — though not specifically stated in the patent — it seems pretty self-evident that the pipe would, at the very least, need to be depressurized.

Otherwise, in the case of a pressurized line, the result would literally be a ruptured line and the ensuing problems or associated damages. Such depressurization is simple to do, and the disruption to services is very minor.

What if the whole reason that prompted the repair work in the first place is because the pipe is obstructed? How would the draw cable be passed through the pipe? The patent does acknowledge this scenario and outline the solution.

Given EPA regulation for working on or around asbestos, the solution isn’t elegant, but it would be effective. A “sheet pile work pit” is driven “adjacent to” the existing pipe, about two feet of the pipe is manually cut open, the obstruction is removed and then the section that was cut out of the pipe is returned and the pit backfilled, so the cut section of pipe will also still be entombed in urethane.

Obviously, such an excavation and blockage removal would be costly and time consuming, but still vastly superior to forcibly removing the pipe.

While the invention is novel, as well as a huge saver of both costs and disruptions, there are some ethical trepidations about the future. Urethane, after all, does not have an infinite lifespan. By encapsulating the asbestos pipe in a layer of urethane, one has, at best, forestalled the inevitable and left the root problem for a future generation — a future community — to solve. The costs and the difficulties have been passed on to a group of people not yet born.

Inflation and population density growth mean those concerns will be greater. Perhaps the ray of hope in all of this is that the forestalling will allow time for future technological advancements that we can’t even imagine currently, which will provide even better ways of asbestos remediation.

Author: Paul D.Q. Campbell is a former engineering consultant and freelance technical writer. He has degrees in engineering, arts, and finance.

Comments