August 2013, Vol. 240 No. 8

Features

After 40 Years, North Slope Again A Tale Of Two Projects

That Alaska would like to commercialize its 35 Tcf in known reserves of North Slope natural gas doesn’t exactly come under the heading of “new news” to anyone in the energy business.

In truth, state and private-sector strategy sessions on how to monetize these vast energy resources weren’t even a new development when many in the industry who are now looking at retirement began their careers. Nonetheless, despite the best of efforts and some bold proposals along the way, no such projects ever came to fruition.

“Let’s just say Alaskans, too, have a healthy skepticism,” said state Commissioner Dan Sullivan, concerning the latest efforts along these lines. “After all, they (Alaskans) have been trying to make this happen for 40 years.”

Still, amid the occasional wink or nudge from jaded oil and gas observers, recent moves by the state Legislature in support of two North Slope proposals – including significant funding for both projects, oil tax reform and the strengthening of the state’s public development corporation – seem to have bolstered industry confidence and support. The tax reform decision, for example, paid almost immediate dividends with BP announcing on June 3 it would invest an additional $1 billion in Alaska during the next five years. The plan includes adding two drill rigs online by 2016, increasing the company’s North Slope total to nine.

“We clearly see the state as being back on the map,” said Sullivan, who has headed the Alaska’s Natural Resources Department since December 2010. “At LNG 17 (the conference held April 16-19 in Houston), I had several side meetings – not just with investors, but with buyers.”

With its approval of $440 million in funding to help move what has been estimated as more than 200 Tcf of natural gas off the North Slope beginning July 1, the Alaska Legislature has taken a big step in the state’s commitment to making sure an estimated $45-65 billion South Central LNG (SCLNG) pipeline project becomes a reality – possibly as early as 2022.

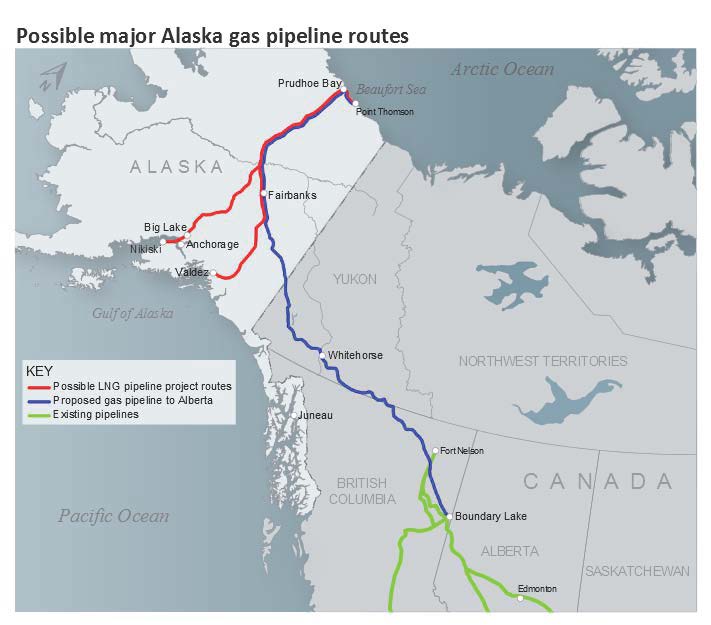

Gov. Sean Parnell recently announced producers ExxonMobil, BP, ConocoPhillips, and operator TransCanada fulfilled the first series of benchmarks for the primarily underground, 800 miles of 42-inch pipeline capable of transporting 3.5 Bcf/d to Alaska’s southern coast. The project will include five state-required off-take points and as many as eight compressor stations, along with two or three 160,000-cubic- meter LNG storage tanks, a terminal with one loading jetty and two berths. There is also the possibility of locating an LNG export terminal near Prudhoe Bay.

“In terms of being able to get gas off the ground, you are literally turning the valve a different way and you have gas production,” said Deepa Poduval, Houston-based principal consultant at Black & Veatch, which has been assisting on the project since 2003. “Right now, they’re producing 8 Bcf/d just at Prudhoe Bay but re-injecting it because there is not a market outlet.”

Amid the flurry of activity, pipeline partner ExxonMobil announced workers will begin surveying 37 streams, 17 lakes and 20 fisheries in the areas near the northern half of the proposed pipeline this summer to fill in data gaps, as well as cutting trenches to study ground conditions. The effort will require adding 150 jobs to the current 300-person workforce employed in the effort. The companies will meet with residents and businesses to better understand community use of hunting and fishing resources.

“Our legislative session was certainly the most successful, consequential session that’s happened in Alaska on energy issues in many, many years,” Sullivan said. “It shows the state’s commitment to commercialized gas with two state-backed efforts.”

Despite these inroads, the process has not been without its sticking points. Parnell, for example, followed his praise concerning earlier benchmarks by recently voicing his displeasure that ExxonMobil, BP, ConocoPhillips had not yet “budgeted or allocated hundreds of millions of dollars related to pre-FEED (front-end engineering design).”

The Republican governor, up for re-election next year, went on to laud the companies for making progress, but “not moving as quickly as Alaskans expected.”

Larry Persily, federal coordinator for the North Slope project, said local politics likely played at least some role in the governor’s comments.

“In truth, the producers have been pretty clear,” Persily said. “They need a reasonable, stable set of fiscal expectations so they can pencil in numbers before they start spending that kind of money.”

Of the four ways Alaska collects money from oil and gas production, the state corporate income tax is reasonably predictable. However, the state production tax, which doubled in both 2006 and 2007 before being reduced this year, is an area of concern in terms of stability, Persily said. Additionally, the terms of Alaska’s royalty share has become an issue among gas producers as has the state property tax, which at 2% of value would translate into a lot of money on a project of this size.

Alaska Stand Alone Project

In addition to funding for the larger pipeline, new state appropriations include $355 million earmarked for work on the design and permitting of a separate state-sponsored 500 MMcf/d, 36-inch pipeline with off-takes for interior and rural Alaska. That project is managed by the state’s public development corporation, Alaska Gasline Development Corp. (AGDC).

Known as the Alaska Stand Alone project, the plan allows the agency to develop, finance and operate the infrastructure, which is viewed as a back-up strategy should the larger project stall. In theory, though, the smaller project could become part of the larger effort, provided the state decides to become an equity partner in that venture.

Sullivan described the AGDC as having been “hamstrung by its inability to really engage with the private sector” prior to the legislative changes, which also opened the way for the agency to hold an open season on the in-state pipeline. The AGDC has already signed a $6.7 million contract for preliminary engineering on a $1.7 billion Prudhoe Bay gas-conditioning plant with a Fluor/WorleyParsons joint venture.

Expedite And Save

In addition to its financial backing for the larger pipe, Alaska is hoping information gathered during previous efforts to commercialize the North Slope – including the $35 billion Denali pipeline, which was canceled in May 2011 – can speed the permitting process on the producer-driven project. It is, after all, possibly the most studied and permitted large project in the United States that has never materialized.

“We’re not saying those (permits and studies) automatically apply,” Sullivan said. “They might be dated, but certainly you don’t have to start from scratch.”

An additional timesaver should be that the right-of-way on the project would parallel that of the Trans-Alaska oil pipeline for hundreds of miles.

Poduval said other advantages that could quicken the process for SCLNG include the current availability of infrastructure on the North Slope – already paid for with oil production – and the lack of political risks and pressures, compared to other proposed projects.

“Alaska has never used natural gas or oil for political reasons like, say, Russia has,” Poduval said. “It’s not shale gas production, so you don’t face the risk something horrible could go wrong environmentally that could bring the whole thing to a halt. And they have 40 years’ experience – a history of reliably delivering LNG to Japan.”

More than growing demand or the emergence of China’s economy, Persily said, he sees higher LNG prices as what makes this attempt to commercialize Alaskan gas more likely to come to fruition than other efforts over the last four decades.

“Until 2008 or so, LNG prices in Asia basically tracked U.S. prices. You could not have afforded to go this route,” he said. “For years, reinjection to force out more oil was the most reasonable use.”

Persily added committing to a gas pipeline is basically “a concurrent decision to keep the North Slope going” that would lead to more oil exploration with the gas treatment facility being available to those who explore offshore in the Arctic.

On the domestic front, Poduval said the argument used against Lower 48 projects designed with LNG exportation in mind – that it will increase domestic prices – doesn’t hold true with the Alaska project.

“They (Alaska gas production) haven’t been supplying the Lower 48 with gas, so we’re not talking about taking anything away from the Lower 48,” Poduval said. “I think the folks in D.C. understand that.”

Conversely, the argument could be made that Alaskan LNG reaching the market actually makes more gas available to the Lower 48 by displacing that demand.

“It satisfies demand that might, otherwise, have to be satisfied by Lower 48 projects,” she said.

Point Thomson On The Move

A major boost to the North Slope natural gas development effort came during the winter when ExxonMobil began building the multibillion-dollar Point Thomson facilities, 60 miles east of Prudhoe Bay. The initial phase of the project is expected online in less than three years. About 80 contractors have been awarded work on the project so far, with Australia’s WorleyParsons topping the winners with $115 million in contracts for engineering, procurement and construction.

Point Thomas is not only one of the largest undeveloped fields in North American – estimated to hold 8 Tcf, or about 25% of North Slope gas reserves – it also contains massive amounts of liquids and oil.

The initial plan is to produce 10,000 bpd of condensate – with bigger things to come. A 22-mile, 12-inch export pipeline will run west to the Badami oil field where the condensate will enter the North Slope pipeline network, eventually connecting with the 800-mile Trans-Alaska pipeline. It will be capable of carrying 70,000 bpd.

A 30-inch gas line will run from Point Thomson to a gas treatment plant in Prudhoe Bay. Operator BP will manage the installation and tie-in to the existing central gas facility and new gas treatment plant.

“We’re trying to accelerate the work plan schedule,” said Sullivan. “There are incentives for them to make a final investment decision by late 2015 or early 2016.

The incentives include a “significant benefit in acreage” the company will be allowed to retain at Point Thomson, he said.

“It’s a project that has waited for its time. The market need is clearly there,” said Poduval. “The interest of the producers is there; the state is motivated to pitch in its share to advance the project.”

LNG Trucking To Fairbanks

In addition to showing support for the two pipeline projects, Alaska lawmakers approved $57.5 million in cash and as much as $275 million in loans to back delivery of truckloads of LNG from the North Slope to Fairbanks.

Under the plan, state agency Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority (AIDEA) would use the cash for an equity stake in the North Slope liquefaction plant and related infrastructure to be built by a private company, which would own a fleet of LNG trucks and operate above-ground storage tanks and regasification equipment.

The project would move gas into a distribution grid for residential use in the Fairbanks area. AIDEA said it is looking at proposals from “several parties” that have expressed interest in the project.

From the state’s perspective, Sullivan said, while a large gas line coming off the North Slope is going to “dramatically effect residents in a positive way,” waiting for that line to become reality simply isn’t prudent.

“What we’ve got to do is start getting gas to the interior soon and building up infrastructure,” said Sullivan. “Most homes are not ‘wired,’ so to speak, to utilize gas” at this point.

The trucking plan indicated that its gas delivery would be more expensive than pipeline shipments to Fairbanks, but would cost less than diesel fuel and could be available several years ahead of any pipeline.

According to a 2011 analysis by consulting firm Wood Mackenzie, Alaska LNG exports would be competitive, potentially generating between $220-419 billion with a delivery cost structure of less than $10/MMBtu. Most competing Australian projects and proposed North American LNG export projects are expected to ship LNG to Asia at between $10-12 per MMBtu.

BP and ConocoPhillips joined the North Slope efforts of ExxonMobil and TransCanada after deciding to halt efforts on the Denali pipeline in May 2011. Denali was to be in service in 2020, delivering 4.5 Bcf/d from the North Slope to Alberta, Canada. The abundance of shale gas made this project irrelevant. TransCanada and ExxonMobil began weighing interest in the Alaska pipeline project with an open season that ended Sept. 14. The companies have not released statements concerning the nonbinding solicitation.

Comments