September 2013, Vol. 240 No. 9

Features

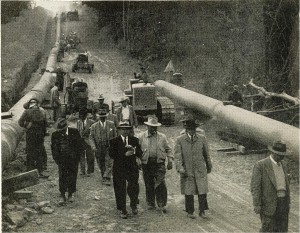

Doug Evans, A Name You Can Trust On Pipelines

When you first meet Doug Evans, you may not realize that his knowledge of the oil and gas pipeline industry is second to none. He is a physically large man whose presence is easily recognizable; beneath that imposing 6-foot-2 frame is a friendly individual who is thoughtful and good-humored with a mind that never stops absorbing information.

Evans is President and CEO of Gulf Interstate Engineering (GIE), a world-renowned pipeline engineering services company marking its 60th anniversary. Evans, 65, has worked in the pipeline business for 40 years, with September marking his 35th year with GIE.

The native of Canada is completing his term as President of the International Pipe Line & Offshore Contractors Association (IPLOCA). In 2005 he served as chairman of the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America (INGAA) Foundation. Both positions in addition to his exposure as head of GIE have made him a well-known figure in international energy circles.

In this interview at GIE’s offices in far west Houston, he talks openly and knowledgably about his company, his career, and his industry. One also discovers that he is an expert at one of life’s most valuable skills: he knows how to listen.

Second-Generation Pipeliner

Evans’ father began working in the business soon after World War II ended. In high school the younger Evans worked summers as a surveyor’s helper. One summer he was working on home development project when he took a call that ultimately changed his life.

“The caller said he heard that I knew something about pipelines,” Evans recalls. “I told him my dad is in the business and he said that’s good enough.”

“They flew me from Toronto to Thunder Bay. I was met at the airport and we drove another few hours to Atikokan (northwest Ontario) where I spent the summer surveying in front of a pipeline construction job. They thought I had pipeline experience, which I guess was inherited,” Evans recalls.

That’s how he spent the next few summers. He was also attending college where he took up engineering, again following in the footsteps of his father who was a civil engineer.

After graduation, Evans worked for the National Energy Board of Canada. He soon left for grad school to earn an MBA.

“Finance was my emphasis. I fully expected to go into something that wasn’t as engineering oriented as pipelines. As luck would have it, I was offered a job with Bechtel working on a pipeline in eastern Canada. I worked summers there between my two years of business school and it turned out great,” Evans says.

Great for him that is, because the project was conveniently delayed a year. After graduating, Evans joined the growing pool of aspiring MBAs seeking job opportunities with banks and other financial institutions. Bechtel, however, wanted that Canadian pipeline project finished and made Evans a lucrative offer that he said was vastly higher than anything MBAs were then getting.

“I thought long and hard about it because I had planned to get into the finance industry, but how can you turn this money down?” Evans says. Banking’s loss was the pipeline industry’s gain. He joined Bechtel’s pipeline department and after the Canadian project was finished he was transferred to Houston.

For the next two years his work included a natural gas liquids project in Saudi Arabia. While he was helping select the route and doing the engineering, GIE competitively bid against Bechtel for construction management of the project and won.

Meeting Red Tyler

Red Tyler was a well-known pipeliner who ran GIE and had met Evans previously. So, once GIE won the bid, he offered Evans a job to manage their Saudi Arabia work. That didn’t sit well with his current employer which filed a claim with Aramco in an effort to block his move. Eventually, GIE got around that by making Evans a proposal manager, a job he kept for a couple years until Tyler insisted he return to project management. And some 35 years later, Evans finds himself still at GIE.

Evans eventually became president of GIE in 1996 soon after Tyler’s retirement. In 2001 he was named CEO of the privately owned company. With the engineering side (GIE), Gulf Interstate Field Services which provides field inspection, its joint venture in India (L&T-GULF Private Limited) and its Russian branch, the company is larger as a whole than it has ever been.

Handling larger projects has been an essential part of GIE’s business strategy but not at the expense of overlooking smaller projects. With the cyclical nature of the energy business, service providers can ignore few opportunities.

“We’ve always been fortunate to get very large projects which we were very organized around,” Evans says. “Our evolution has been to become capable of handling a lot of small projects as well as the large projects, which meant we had to dramatically change some of our organizational structure, especially in regards to beefing up our administrative support, our processes and our procedures.”

“For many years, we did our work for a client the way they wanted. As the business evolved, many companies were involved in mergers, acquisitions, and other circumstances where they no longer had ‘the way’, so they looked at us and asked ‘what is your way?’.”

That ultimately required the ability to successfully mesh a client’s preferred methodology with that of GIE. Today, that means having a larger staff working behind the scenes and using state-of-the-art tools. Once that was CAD (computer-aided design); now it is GIS (geographic information systems). GIE has made a sizable investment in developing a GIS system that will become the backbone of its business platform, determining how they will engineer, control and report on projects.

Focus On Quality Control

For this to work, GIE required a renewed emphasis on quality and Evans offers a primer on what needed to done and why.

“As we’ve had to add people and grow, we found that procedures and processes can’t be taken for granted. A few years ago we felt people weren’t necessarily checking their own work nor were they overly concerned about what was happening in the next phase of a project. They did their piece of work and went off to something else, deciding that it wasn’t ‘mine’ until it was actually built.”

“We made a huge effort to train people on our processes, developing a quality culture where everybody wanted to do the best they could. I’m hoping that’s turned the corner,” Evans says.

GIE has seen a dramatic shift in the average age of its engineering staff with nearly 50 men and women in their 30s or younger. In fact, a major project with Pacific Gas & Electric involved data research into hundreds of miles of pipelines that comprised hundreds of thousands of documents and associated pieces of paper. GIE hired 35 young engineers in one year for that job and is continuing that trend because Evans likes the results.

“The vast majority have blossomed into good design engineers with management potential,” he explains.

To assist young engineers in the training process GIE developed GAP, (Gulf Associate Engineer/ Project Controls Program). Rather than assign them to a client and charging them for their services, after they are hired GIE trains them as cost-control experts for a year or so. This offers the option of moving into the business side involving cost and scheduling or moving into engineering.

Pipeline engineers are a hot commodity with service companies and operators vying for the most talented individuals. What would induce a young man or woman to design pipelines?

Evans offers a humorous anecdote that may speak to many of today’s young professionals.

“Two years ago I had a breakfast for new employees and at one table a young engineer asked, ‘what’s a benefit?’. We were his first job and he really didn’t know what a benefit meant. So it’s pretty easy to say they weren’t focusing on benefits and maybe not even necessarily for salary, but for something challenging and exciting to do.

“The oil and gas business in Texas is booming, as is Houston. The young people want to be part of something that is exciting and booming. This is tempered, of course, in that most of our new hires are engineers so they’re a different sort anyways, right?”

“They’re likely to work for us because right out of school they can put into practice what they’ve studied for. They see that the work satisfies their technical requirement to build something. The student is able to contribute more now than a student coming out of school before could; we’re able to take advantage of that by putting them to work more quickly than big companies probably can,” he says.

The World Of Pipelines

During this lengthy career Evans has worked around the world on many important pipeline projects, including some that never were built (or still not yet) such as the Alaska Natural Gas Pipeline project which was canceled in 1981 after he spent three years on it. He later spent several years on projects in Saudi Arabia as a natural gas project manager for Aramco; worked in Yemen on an oil export pipeline project for Hunt Oil and Exxon; and was involved with another project in Yemen for Canadian Occidental.

Other important pipelines that Evans had a hand in include Peru’s Camisea Gas Pipeline; Ecuador’s OCP oil pipeline; Reliant’s East-West gas pipeline in India, and most recently the Rockies Express (REX) Pipeline in the U.S. Those experiences have shown Evans that people elsewhere share different views of pipelines.

“The people we’re working for perceive pipelines as being very critical. In many of the foreign countries they were the first or biggest project going on, so it was somewhat mystical to them. Our clients have reached out for American help because they are somewhat frightened by the concept of pipelines. But they always embrace us.”

“We’ve had better luck getting pipelines built in other parts of the world than we do here in the U.S. Keystone XL is an example of what can happen to pipelines in the U.S.,” he says.

GIE has worked since 2004 on the CPC (Caspian Pipeline Consortium) project, which is expected to finish next year. That 940-mile project involves moving Kazakh oil through Russia to the Black Sea port city of Novorossiysk. The only means of exporting that oil has been via costly rail cars.

Pipelines are not just the most economical way, but oftentimes the only method of transporting oil. This was demonstrated a few years ago in Africa at another project GIE helped design, Exxon’s vaunted Chad-to-Cameroon oil pipeline.

“There was no other way; you couldn’t even use trucks. Without a pipeline that oil couldn’t go to market, period,” Evans recalls.

The Benevolent Dictator?

Despite his steady avuncular demeanor, Evans has never been one to avoid the difficult decisions required to manage a successful energy company. Times can be just as challenging when there is too much business as when it lags. Evans doesn’t feel his voice should be the only one heard.

“I like to think that I’m a benevolent dictator,” he says.” I’ve either had to remind people or had them remind me that business isn’t a democracy, but I try to get everybody’s opinion and hear others’ thoughts. Sometimes I’ve been accused of rejecting too early other people’s thoughts and maybe that inhibits some responses, so I’ve worked at not trying to shout down others.”

“I’ve realized that time marches on so I’ve made a conscious effort to try to develop the next group of leaders within the company. I’m not quite sure I did it early enough but I am in the process of doing it,” Evans says, though he gives no indication of retiring anytime soon.

Those new leaders will inherit a vastly different world, thanks to the ongoing shale revolution. It’s something that Evans, like most experts, did not see coming.

“A few years ago, we tried to reawaken our international business because we thought the U.S. market was going to be slow for pipelines, maybe not quite so slow for compressor and pump stations.”

The Numbers Crunch

“The impact of shale gas, shale liquids, and shale oil is a blessing, albeit a double-edged one. We reawakened our international market yet we’re so busy in the U.S. that we really haven’t been able to take advantage of some of the opportunities internationally. In fact, we’ve had to turn some down because of a lack of resources, which is unfortunate,” he says.

To maximize its potential, the industry must resolve several ongoing challenges and that calls for more resources. The number of qualified engineers, designers, cost control/procurement people must increase, Evans says.

“A few years ago the majors were undergoing so much M&A activity they also stopped hiring a lot of university graduates and then training them. That’s where we would often find our people. That’s changed. Now Big Oil is back into hiring but there is a continued lack of qualified people.”

“GIE is constrained right now on what we can do by the number of people we have. We have more opportunities in front of us and I’m sure our competitors and clients are in a similar situation,” he says.

Then there’s the increased competition with the big bucks of Big Oil to lure engineers, driving GIE to hire more engineers fresh out of college than retraining older, experienced engineers.

“That’s why we’re still recruiting out of college because, given a choice of taking an experienced engineer from a different industry or young engineer, we’re opting more toward training the young than retraining the older,” Evans explains.

“We’ve been pretty successful hiring some of these engineers because they can have a more immediate impact here, especially with their own self-esteem and career path, than they could with Big Oil. Money-wise, that’s always a challenge. We’re okay there as well as long as we continue to be fiscally prudent,” he says.

Competition In A Booming Business

With the energy business in high gear, competition among service companies has also picked up. Enlightened clients know better, Evans suggests.

“We have some clients who view engineering and construction management services as a commodity, and when they do, it becomes very competitive. Fortunately, I think they now recognize the value added, so we’re getting our shot at work based more on who we are than what we cost.”

“We just turned down a major project and walked away from a very large international project because we would not reduce our rates. We don’t need to. We have clients willing to pay what we consider is a fair price and we’ve got more than we can do now.”

“So, when it becomes more work than there are people to do it, it’s not so competitive anymore,” he says.

Despite the sometimes onerous regulatory environment in the U.S., Evans says it is still easier to do business here than most places in the world. He offers a major reason why.

“There is a more experienced, savvy group of people you are dealing with as clients. Internationally, they are often very smart, book smart perhaps, not necessarily business smart. Unfortunately, it’s a lot more of checking the boxes. Let’s say we have an engineer with 15 years’ experience in gas pipelines, according to the resume, but we failed to say he also worked in oil, so they’ll reject that person.”

“Within reason from a design standpoint, gas and oil are the same, but you didn’t check the right boxes. We are constantly dealing with this – the failure of international customers to truly understand our business, where domestic customers are more discerning.”

A Defining Moment For GIE

Any company’s history includes those moments that will define its future. For GIE, the period of 1983-84 when the domestic energy industry was at near standstill was such a time.

“That was a critical time for us because we had almost no work and really didn’t know what our future was going to be. This was just before we got that big project in Yemen. That was defining what our future was going to be,” Evans recalls.

Managing a company in uncertain times requires a special set of skills, ones that you may or may not pick up in business school. Here’s how it works, according to the Evans School Of Management.

“It is a much different attitude,” Evans professes. “When you have money, you can spend money; you can try a few things that might not work. When you don’t have money, you have to marshal your resources far better. You can’t chase as many projects; you have to just focus on what you think you can get.”

“You can’t negotiate quite as tough on some of those things; when it’s tough, the client is always right. When things aren’t quite so tough, it’s more mutual.”

“One of the scarier things in our business is consequential damages (special damages that can be proven to have occurred because of the failure of one party to meet a contractual obligation). As a business, we would almost never consider consequential damages. But in the past, to get work, sometimes we have had to,” he says.

Steady Growth Of IPLOCA

Nearing the end of his 2012-13 term as President of IPLOCA, Evans says progress has been made on one critical goal for these members who represent more than 40 countries with oil and gas pipeline construction capability.

“The approach to doing business has always been a little different but one issue we have collectively shared is the desire to have our workers come home at night safely. The western contractors have been fairly successful but some of the developing countries haven’t, so we’ve made a commitment to develop safety processes, plans and goals to the entire international industry,” Evans says.

IPLOCA members also face their own specific challenges, depending on where they work, as Evans explains.

“Europe is a dog-eat-dog world for pipeline construction. There’s not much work; it’s small, and people are buying work just to keep their equipment and their people busy. It’s unlike the U.S. where you can’t find enough people, be it construction or engineering.”

“The Far East is not booming as much as us but is doing quite well. China is pretty much closed to most Western contractors but they are building thousands of kilometers of pipe every year.”

Members are also facing different pressures and rewards from operators, depending on where they work.

“Consistency is one of the biggest desires among members as to risk-and-reward sharing from clients,” Evans says. “We’ve worked on common-contract wording but it really hasn’t produced the results because at the end of the day you still end up using the client’s contracts.”

Evans also expounds on the changing relationship between operating companies including national oil companies (NOC) and service providers such as GIE. One certainty is that they all demand more from their service company.

“Many of these companies, especially some of the NOCs, have many, many engineers involved in operations but then discover they are not focused on doing specific projects. That’s been a struggle over the years but I’m finding today there is better recognition of when you actually need a service company.”

“The Exxons, Shells, BPs always understood that and always turned to service companies to get work done. The NOCs tried to do it themselves, but they’ve now opened up and said they see the value,“ Evans says.

And they do expect the service company to assume more of the risk, though the anticipated reward is questionable.

“They are not necessarily throwing out the reward to get the contract. One of the biggest risks in our business is schedule delay. They’ve tried in many different formats but the most common is liquidated damages (an agreed-upon means of compensation for the breach of a contract) on meeting certain schedules. So much of what we do and come up against is dependent on others – environmental issues, land, material supply, permits, change of mind, shareholders, funding, etc.

“It’s hard for us to control the schedule. We’re much better reacting, but when we have liquidated damages for scheduled milestones, it’s just a nightmare,” he says.

IPLOCA membership has seen a surge in the past couple of years with new members outnumbering those leaving. One significant change has come in the Americas. IPLOCA now divides the Western Hemisphere into America North, consisting of Canada and the U.S., and Latin America consisting of Mexico and South America.

Evans says that many American pipeline construction companies didn’t join IPLOCA because their work was confined to the U.S. and Canada.

Under Evans’ leadership, IPLOCA has worked to explain to its American and Canadian brothers that they are nonetheless still part of the international pipeline community, much as French contractors who only work in France are members.

“They need to understand how people around the world do pipelining and should meet some of them, learn their techniques, equipment and approaches to business,” he says.

The effort seems to have borne fruit as the number of American members has risen from six to 16 the past two years out of IPLOCA’s total of 270.

Those new members can also benefit from IPLOCA’s determination to encourage more young people to work in the offshore and onshore pipeline sectors. Evans is spearheading a new IPLOCA initiative that he hopes to see approved shortly involving competitive scholarships to encourage young people to enter or remain in the industry.

In addition to safety, there is a big emphasis on new technologies. Evans says IPLOCA will continue to foster initiatives and research through the Novel Construction Initiative in collaboration with INGAA and PRCI, with more emphasis on new technologies. The goal is to stimulate innovation in the technology and processes required for execution of onshore pipeline projects by engaging all contributors to the pipeline construction supply chain.

The Art Of Listening

To successfully chair an association requires building a consensus among members. That means the President needs patience, and a willing ear. With plenty of experience behind him, Evans offers a few suggestions to other would-be association leaders.

“In many cases it’s like the old expression “herding cats”. The representatives of the associations I’ve chaired, INGAA Foundation and IPLOCA, are usually executives in their own businesses for large companies and everyone has an opinion that most want to express.”

“As a chairman you’ve got to ensure that everyone has a voice and try to do that equally. Consensus is very important in those associations as well as trying to follow the charter. Each association has its own charter. For IPLOCA, the most important pillar is the social networking, which is our convention, and keeping our goal on track to have a successful meeting with opportunities for members and spouses to get to know each other.”

“At the INGAA Foundation the main pillar is to promote the building of safe, reliable pipelines and concentrating on whatever barriers there are to that and figuring how to overcome them. So it’s a little more technical and requires putting plans together in the way of studies.”

“Those two associations are quite different in that aspect but for both of them the common element is that everybody is there to articulate, has an opinion and wants to express it, so you have to listen,” he says.

Evans also credits his wife of 40 years, Liz, as a key to his success, a partner who has stood by his side for his entire career. Those who know the Evanses say they are very close and work well as a team. He has two children, Ryan Evans and Arwen Mallet, both married. Arwen has the Evans’ two grandchildren, Kyra 3, and Ace, 2.

When he isn’t at work or traveling around the world on business, Evans is an avid golfer, salmon fisherman and once was a frequent tennis player. He is on the board of directors at the Crossroads School, a not-for-profit, academic institution created to address the educational and emotional needs of children with learning differences with the ultimate goal of transitioning the each student back into a conventional school setting. He also previously served as the Director of the Texas Gulf Coast Chapter of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

Comments