August 2014, Vol. 241, No. 8

Features

Sharing Challenges In The Eagle Ford Shale

Like most stories about Texas, the one that’s being written in the Eagle Ford shale is full of big dreams, big dollars, and big results.

The play itself is huge, covering an area of 20,000 square miles, it spans 25 south-central Texas counties and is roughly the size of Croatia. Capital expenditures there by energy companies are sky-high, reaching $28 billion through the end of 2013, if predictions by global consultants Wood Mackenzie held true.

And production is immense: Late in 2013, the Eagle Ford beat the Bakken in the race to reach the coveted 1 MMboe/d. Some experts even predict on the strength of Eagle Ford and Permian Basin production, by the end of 2014 Texas could become the world’s second-largest producer of oil behind Saudi Arabia.

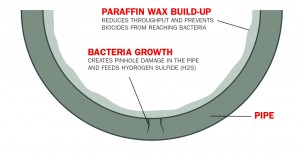

So who would think something as small as bacteria might affect this narrative? Bacteria have been an ongoing issue for Eagle Ford operators since development began in the shale play in 2008. Not only do bacteria eat into pipelines, creating tiny pinholes, they also contribute to the growth of hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a naturally corrosive and deadly gas.

High levels of paraffin wax in the area’s highly variable crude are a problem, too, leaving fouling deposits in pipelines that threaten to reduce throughput. Additionally, concerns over water use continue to occupy the minds of operators and environmentalists alike. In short, companies are encountering operational challenges they hadn’t experienced in conventional developments.

Most operators in the Eagle Ford are candid about the issues they’re facing. The good news is they’re looking to one another for answers, finding common ground and sharing information at various forums in the United States and elsewhere. Operators are also leaning more on vendors for support, a point brought home by Valerie Mitchell, general manager, of Newfield Exploration Company, who called for stronger partnerships between service companies and operators during her talk in March at the Midcontinent Developing Unconventionals (DUG) conference in Tulsa, OK.

An Unconventional Opportunity

The Eagle Ford shale in South Texas is one of the most complex unconventional plays in North America in terms of geology and geophysics. Because the rock unit had such low permeability, preventing oil and natural gas from flowing through it into a production well, the Eagle Ford had garnered little industry attention. That is, of course, until 2008, when Petrohawk Energy, which has since been purchased by BHP Billiton, Ltd., demonstrated the efficacy of fracking in the Eagle Ford, drilling a well that had an initial flow rate of 7.6 MMcf/d.

Although fracking opened the Eagle Ford, the play’s unusual characteristics continue to make it difficult to deal. In their report titled, “An Analytic Approach to Sweetspot Mapping in the Eagle Ford,” Murray Roth, Michael Roth and Ted Royer describe the Eagle Ford as “grossly depth-driven.”

In the Eagle Ford, the report explained, oil is produced at depths of 5,000 to 8,000 feet to the northwest, with the play grading through condensate and natural gas liquids until dry gas is produced at depths of 10,000 to 12,000 feet to the southeast.

Combined with well-to-well production variability, those depth issues make it more difficult to find sweetspot locations, drill and complete wells, and optimize production. Those tasks can be so arduous, in fact, some American majors have given up and are selling their Eagle Ford assets; Royal Dutch Shell is among them.

Abdel Zellou, a U.S. midstream and gathering market expert with T.D. Williamson, said he learned at a recent Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE) workshop in Dubai that the main reason for the pull-out is Shell simply doesn’t hold sweetspot areas in the region. Shell confirmed its plans to “concentrate on asset opportunities with better economic metrics elsewhere in North America and around the world.”

The company hasn’t announced a buyer for its 106,000 acres of Eagle Ford leases, which are located in Dimmit, LaSalle, and Webb counties and produce about 32,000 BOE/d.

Although Shell is one of the first integrated oil companies to publicly back away from U.S. shale plays, the Hague, Netherlands-based major doesn’t appear to be alone in having second thoughts about shale.

The Houston Chronicle reported that two years ago BP wrote down $1.1 billion on its shale gas assets because the value of reserves dropped along with natural gas prices. This was after BP’s net share of production in the United States fell 15%. It was also noted ExxonMobil’s 7% return on capital for its U.S. upstream business last year was dwarfed by the 24% return it collected on its international energy production business.

While the question remains whether certain majors will continue to participate in the shale-induced energy surge, there’s no doubt the Eagle Ford has created a financial bonanza for others. After all, production is 25 times higher than it was just four years ago.

Somebody’s got to have a hand in all of that growth, and it appears the winners are independents and small players. In fact, recent Bloomberg data showed that in the three top shale plays, small companies beat out the majors 5-to-1 in terms of acreage.

According to Standard & Poor’s, the top Eagle Ford leaseholders include EOG Resources, Chesapeake Energy Corp., Apache Corp., BHP Billiton, Ltd., ConocoPhillips, Marathon Oil Corp., Anadarko Petroleum Corp. and Pioneer Natural Resources.

Eagle Ford Challenges

Now that that some of the key Eagle Ford characters have been introduced, it’s time to get back to bacteria and the other antagonists.

At the Tulsa Developing Unconventional Gas (DUG) conference, Tom Petrie, of investment banking firm Petrie Partners, did a good job of identifying the four general categories of risk faced by upstream and midstream companies operating in the Eagle Ford:

• Environmental

• Infrastructure

• Pricing volatility

• Shifting globalization

Zellou agreed with Petrie, going a step further by suggesting that upstream and midstream operators have different concerns that fit broadly into the list.

“Upstream companies are challenged more by the sheer geology of the Eagle Ford, plus their need to capture accurate reservoir data,” Zellou said. “Midstream operations are distinguished by an entirely unique set of challenges and expectations.”

According to Zellou, the chief issues for midstream operators in shale plays are:

• Infrastructure and infrastructure maintenance

• Paraffin buildup

• Internal and external pipe corrosion

• Environmental issues and constraints

• Regulation of gathering lines

• Lack of skilled personnel

• Price volatility

Obviously, service providers can’t dampen price volatility or alter hiring patterns, but they can help operators better respond to other Eagle Ford challenges. Consider infrastructure maintenance, particularly as it relates to paraffin and corrosion.

Although a lack of infrastructure is a problem in the Marcellus and Utica shales, there’s generally sufficient infrastructure in the Eagle Ford to avoid bottlenecks from the wellhead.

Instead, the challenges in the Eagle Ford involve operators using existing pipelines intended to move conventional natural gas to now gather wet-gas. The reuse means problems are cropping up that might not occur in purpose-built pipelines.

For example, Eagle Ford wet-gas is full of natural gas liquid (NGL) condensates that vary in composition and concentration from well to well. Recently, Pipeline & Gas Journal reported engineers at San Antonio’s Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) called particular attention to the fact that there were considerably more pipeline-clogging hexanes in Eagle Ford samples than in those from other shale plays.

Eagle Ford production is also laden with paraffin, which can coat the top and sides of pipelines, allowing bacteria-infused water to collect at the bottom. The water can cause corrosion while the bacteria can create pinhole damage and feed the growth of potentially deadly H2S.

“Paraffin is a problem across the board in the Eagle Ford. One operator told me they had a quarter-inch of paraffin covering 75% of their pipe,” said Steve Appleton, regional general manager with T.D. Williamson. “And the paraffin buildup is creating unanticipated issues with harmful bacteria. Operators run biocides in their lines to kill the bacteria, but if the bacteria are beneath the paraffin, the biocides can’t reach it.”

To combat these risks, Appleton said, service providers are helping operators implement more rigorous pigging schedules. Not only does regular pigging promote productivity, it presents an economic opportunity, allowing valuable NGLs to be collected for sale to refiners.

High Water Use

Because water is the largest component in fracking fluids, water use and conservation are key concerns in every shale play. But in the Eagle Ford, the issue is further complicated because Texas is in the middle of a multi-year drought.

In February, Ceres, a Boston-based investor group focused on sustainability issues, said the Eagle Ford used more water during an 18-month period than any other shale region – a total of 19.2 billion gallons, or 4.5 million gallons per well. Ceres found that 98% of the Eagle Ford wells were in areas of medium or high water stress, with 28% in areas of high or extreme water stress.

Ceres’ report said operators need to institute more creative water management. Specifically, they should minimize freshwater use, Ceres said, and undertake better long-term planning for the water infrastructure needed to maintain oil and gas development. The group advocates water recycling, which is more common in the Northeast, although the Eagle Ford’s first water recycling facility was installed in 2011.

These suggestions hardly took operators by surprise. Potential water solutions are a stock item on the agenda at unconventional events and were the centerpiece for the E&P Technology Panel at last September’s DUG Eagle Ford conference in San Antonio.

Has that information-sharing brought forth any progress? Well, Ceres did acknowledge some operators are ahead of the game, crediting Pioneer Natural Resources for installing evaporation covers on water pits.

Also, Omar Garcia, president and CEO of the industry group South Texas Energy & Economic Roundtable, said more operators are stepping up. Speaking to the San Antonio Express-News, Garcia noted some companies are reporting a decrease in water use of as much as 30%. He believes freshwater use in the Eagle Ford should continue to drop as new technologies are introduced.

Rising Regulation

Although the water used in fracking in the Eagle Ford and other U.S. shale plays is exempt from key federal regulations, pipelines are a different story. The U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) is considering regulating gathering pipelines. If the regulation passes, it will likely require integrity inspections, creating more pressure on service companies to provide increasingly robust pigging and inline inspection services. But even if the federal government doesn’t act, some states are already taking matters into their own hands.

In December, North Dakota – home of the Bakken shale – announced that about 18,000 miles of previously unregulated underground gathering pipelines were now under the jurisdiction of the state’s Industrial Commission. Lynn Helms, director of North Dakota’s Department of Mineral Resources, called the move the “biggest amendment of oil and gas rules in North Dakota’s history.”

In April, state Public Service Commission Chairman Brian Kalk said it is likely his agency will ask state lawmakers to create an inspection program for the North Dakota’s oil pipelines, a proposal coming on the heels of a 20,600-bbl oil spill in a farm field near Tioga.

Although there’s no similar local action underway in Texas – a state that Zellou described as being friendlier than most to the oil and gas industry – PHMSA regulations might make regulation of rural gas pipelines a reality within five years.

Commitment Remains

Despite the challenges facing them, Eagle Ford operators are almost unanimous in their commitment to the region. According to research firm GlobalData, drilling and development in the play are expected to continue unabated, with nearly all of the more prominent operators projecting at least five more years of drilling at the current pace.

“We’re still in the infancy of the shale revolution,” Zellou said, adding that some E&P companies are still figuring out the size of their Eagle Ford reserves.

Comments