December 2014, Vol. 241, No. 12

Features

Gas Infrastructure Aging Gracefully Despite Flawed News Story

While statistically pipelines remain the safest method to transport natural gas and liquids, growing demands on the aging infrastructure has increasingly pointed to the need for upgrades – sometimes tragically so.

Despite federal Department of Transportation (DOT) statistics that show pipeline incidents resulting in serious injury or death have dropped nearly 50% over the last 20 years, sporadic high-profile events, including the deadly incident in New York’s East Harlem* this year and the Allentown, PA** explosion in 2011, have highlighted the need to hasten the repair and replacement of the most at-risk lines.

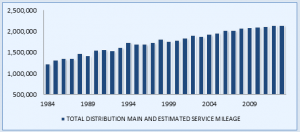

A report from the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), which sets national policy on hazardous materials transportation, shows inroads have been in the last decade. Nationwide, total miles of cast-iron distribution mains have decreased almost 24% since 2004. Meanwhile, the number of cast- or wrought-iron (less brittle, more resistant to corrosion than cast iron) service lines was reduced by 73% during the same period.

“It is important to realize that it is just not logistically or economically feasible to replace all the cast-iron or bare-steel pipe at once – nor does it all need to be replaced right away,” said Lori Traweek, senior vice president and chief operating officer of the American Gas Association (AGA).

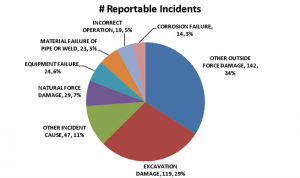

Still, several recent news articles have concentrated on the “worsening condition” of older pipe as a major threat to public safety. This, despite PHMSA data going back to 2004, which points to only a relatively small percentage of “reportable incidents” being caused solely by infrastructure deterioration.

A recent USA Today article, “Look Out Below: Danger Lurks Underground From Aging Gas Pipes,” for example, uses an interactive map based on PHMSA “reportable incidents” in citing what it calls pipelines “prone to failure.” A feature of the online version of the article bears the heading, “There is a destructive gas leak every two days in the USA,” and allows readers to enter local zip codes, which then purport to display a map showing incidents dating back over 10 years.

In the case of ZIP code 77006 (central Houston), for example, a plethora of leaks for the area appears on the screen, but most took place in the ocean or well outside of Houston itself. Additionally, the majority of these “destructive incidents” – both in the Gulf of Mexico and on land – did not cause injury, and most of the incidents causing injury involved one person. Reasons for leaks varied but third-party excavation, vehicular accidents and operator error were the dominant causes – not pipe deterioration.

“No state has experienced more major gas leak incidents [167] or more gas leak deaths [62] than Texas,” an accompanying voice recording warns those entering the Houston zip code. But a closer look at the expansive greater Houston area itself showed the city had experienced four leak-related deaths since 2004; the causes listed were excavation, miscellaneous, explosion and unknown.

“I’m not sure what can be done to quell public concerns,” said John Erickson, vice president of operations for the American Public Gas Association (APGA). “The recent USA Today articles sensationalized the issue far beyond the actual degree of risk to the public.”

Erickson also cited the example of a TV station in Washington, DC that obtained a redacted version of the local utility’s federally required Distribution Integrity Management Plan (DIMP), and then “mischaracterized” it as a “secret list” of dangerous gas pipe.

“Relative risk is a difficult concept to explain to the public, when in fact, the highest relative-risk segments in a utility does not mean the pipe is unsafe,” he said.

While the natural degrading of iron, or graphitization, makes cast-iron pipelines more susceptible to leaks from joints or cracks, by far the biggest threat to cast- or wrought-iron pipe is earth movement caused primarily by groundwater fluctuation, seasonal frost or digging.

In fact, effects of excavation and damage by other outside forces accounted for over 60% of all reported pipeline incidents between 1995-2004, according to statistics by the federal Office of Pipeline Safety which has since been re-organized as PHMSA. Additionally, research by utility software provider Opvantek, Inc. found that since 2010, over 75% of unintentional gas releases were caused by something other than aging infrastructure alone. Excavation damage was faulted in 29% of the incidents.

It is this type of distinction that AGA and others in the industry try to make: The age of the pipe, while certainly a factor, is not the primary characteristic of performance or safety.

“You take the explosion in New York [which took place in March, killing eight and injuring 48] and all the talk about the pipe being installed in the 1880s or the 1890s, as an example,” said Mark Bridgers, a design and construction consultant at Continuum Advisory Group who has worked with a number of gas utilities. “The flipside is that pipe functioned appropriately for 120 years, and there is a strong argument to be made that it could have continued to function had the gas not collected in that building, ultimately resulting in an explosion.”

Where earth movement does occur, it is especially significant to cast-iron pipe, which is strong and hard, but also brittle. While cast iron resists corrosion its joints are put together in a way that works best under very low pressure. Vehicle movement aboveground and digging can cause cast-iron pipes to crack or break, or force the joints to wiggle loose, causing leaks.

A look at accidents, primarily those investigated by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) involving gas distribution lines seems to bear out that earth movement is the biggest cause of fatal incidents, dating back to 1994:

• March 2014, Manhattan, involving an 8-inch cast-iron gas pipe is currently under investigation.

• February 2011, Allentown, PA, a 12-inch cast-iron main break is blamed on failure to repair a “Class B” leak, discovered in 1979, within “a reasonable amount of time.”

• January 2011, Philadelphia, a 12-inch cast-iron gas main ignited as crews worked to patch a high-pressure gas main break.

• December 2010, Wayne, MI, crew installing a gas main failed to “hand-dig,” as required, to locate an underground gas pipeline it later struck.

• December 2008, Rancho Cordova, CA, fault was found with “use of a section of unmarked and out-of-specification polyethylene pipe with inadequate wall thickness that allowed gas to leak.”

• November 2008, Plumb Borough, PA, a 2-inch carbon steel natural gas distribution line cracked. Though corrosion was present, investigators concluded “dents and the deformation in the pipeline indicate that it had been struck from below by something more powerful than a hand shovel,” causing its failure.

• December 2005, Bergenfield, NJ, a 1.25-inch steel service line broke due to failure “to adequately protect the natural gas service line from shifting soil during excavation.”

• July 2003, Wilmington, DE, a 1.25-inch unmarked steel service line broke after being struck by a backhoe, which caused the line to break inside a nearby basement.

• January 1999, Bridgeport, AL, a 0.75-inch unmarked steel service line was broken during excavation.

• December 1998, St, Cloud, MN, a 1-inch, high-pressure plastic gas service pipeline was ruptured by a communications network installation company digging to install a utility pole.

• October, 1994, Waterloo, IA, a 0.5-inch polyethylene pipe broke as the result of “stress intensification, primarily generated by soil settlement at a connection to a steel main.”

• June 1994, Allentown, PA, a 2-inch steel gas service line exposed during excavation separated at a compression coupling about 5 feet from the wall of a retirement home. Gas flowed underground into the building, which exploded.

“The leading cause of accidents in both transmission and distribution systems is damage by digging near existing pipeline,” Traweek said. “Frequently this damage results from someone excavating without asking or waiting the standard 48 hours for the gas company to mark the location of its lines.”

AGA points to education as a means not only to build public confidence in the industry, but also to reduce incidents to an even lower level. An example of the attempt to educate the public is the 811 “Call before you dig” campaign.

“Excavation damages for all underground facilities have decreased by approximately 50% since 2004,” Traweek said. “This improvement is due in large part to work done by local natural gas utilities to promote the use of Call 811.”

Cast Iron By Nature

Due of its nature, cast-iron pipe is not a good fit for statistical models used in predicting vulnerability and risk. That is because leaks involving cast iron tend to occur at joints and do not necessarily hinder pipeline performance. As a result, they are “non-incidents.” You can calculate an average performance, but that average is not representative of either the low-end or the high-end set of data.

“Bare steel, particularly through statistical analysis, is much more predictive because you don’t tend to have the extremes of cast-iron pipes, where either nothing happens or you have a catastrophic accident,” Bridgers said.

According to PHMSA, 10 states contained 83% of the nation’s cast- or wrought-iron distribution main miles in 2013, despite their collective total having dropped by 17% since 2004. For the same period, reports by 10 companies showed they accounted for more than 57% of this mileage, despite achieving 10% reductions.

A look at the PHMSA numbers for service lines told much the same story, only the percentages were more extreme – 10 states account for 98.5% of cast- or wrought-pipe. This is despite collectively decreasing their total by 43% between 2004-13. In the case of service lines, 10 companies accounted for 96% of cast- or wrought-iron service lines in 2013, which was a 71% reduction of these companies’ totals for that period.

Public gas systems are fortunate to have less bare steel and cast-iron pipe than the national average, according to Erickson, with bare steel making up 1.3% of those system’s mains vs. 4.9% of all U.S. utility mains. Cast iron accounts for 2.3% of public gas system mains vs. 2.6% of all utility mains. Out of about 1,000 public gas systems, he said, fewer than 100 have any bare steel or cast iron.

“The public gas systems that do have bare steel and cast iron are replacing the highest relative risk pipe first,” said Erickson. “Cost is a factor, but the availability of qualified crews, permitting and the disruption due to major construction projects are also factors.”

“Risk” and “risk tolerance” are by their nature relative terms, moving beyond data-driven information to the perception of those assessing the situation. Whether that is the homeowner, utility operator or someone else, it involves a lot of gray area.

“The question is how you get those to a level that is manageable and considered reasonable,” Bridgers said. “Of course, everybody’s definition of ‘reasonable’ is different.”

Huge Effort Underway

To its credit, the industry has already replaced thousands of miles of pipe, but a massive effort remains. It can cost $1 million a mile to replace aging pipe, according to consultants, depending on terrain and other factors; that cost is generally passed on to the customers. According to the DOT, the pipeline network carries natural gas to over 177 million Americans, a figure which is growing daily.

The National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissions (NARUC), the group of public commissioners that regulate individual state utility services, maintains that, overall, the industry “has done well” in preserving a safe and reliable system.

“Many operators have been systematically replacing vintage pipelines for decades,” said Robert Thormeyer, director of communications for NARUC. “Typically, there is not a one-size-fits-all approach across the country, and the same is true within a single state.”

Thormeyer said in the states with the most cast-iron and bare steel the pipe can be difficult to replace for several reasons, including municipal restraints on traffic control, pavement disturbance moratoriums and the need to coordinate work with local capital projects.

“These limitations do not relieve the utilities from their ultimate responsibility of replacing infrastructure in a way that maintains the integrity of the system,” he added.

The DOT estimates 30,000 miles of cast-iron pipe still carries gas in the United States, with the highest percentage of these mains located in the older eastern cities such as New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore and Washington, DC.

Among some of the larger infrastructure replacement programs underway in urban areas:

• Integrys, which services Chicago through its Peoples Gas distribution system, began a program in 2011 that has replaced 35,000 service pipes and retired 245 miles of its cast-iron conductor system so far. The company plans to replace about 2,000 miles of cast-iron mains and 300,000 service pipes and meters within 20 years.

• In New York City, National Grid has replaced over 158 miles of pipe and associated services from 2009-13. The company plans to replace over 1,900 miles of mains and 25,000 services during the next 25 years. Separately, Con Ed, which serves the East Harlem neighborhood affected by the fatal explosion, plans to have replaced 828 miles of cast-iron and steel gas mains by the end of 2016. Federal records show it has replaced about 24 miles of that total so far.

• Philadelphia Gas Works is concentrating its efforts on 1,500 miles of cast-iron mains, comprising half its system. The company, which has replaced 28 miles of mains, told philly.com it is on pace to replace most of its cast-iron mains in the next 50 years.

• In Boston, National Grid has replaced 129 miles of natural gas in the last 10 years. The company also accelerated the number of miles of older mains it upgraded this year. Nation Grid plans to replace the 438 miles of remaining cast-iron, wrought-iron and unclad steel pipe in the Boston system over the next 20 years.

In all, PHMSA data showed utilities have replaced about 10,000 miles of the most vulnerable cast-iron pipe from 2004-13. The companies replaced an additional 17,000 miles of bare-steel mains during the same period, leaving about 56,000 miles still in operation.

In addition to replacement programs, safety efforts have been bolstered by improved tracking equipment that companies use to reduce the frequency and extent of leaks. One of the tools most often used by utilities is Optimain DS, which continuously monitors mains and assesses leaks.

Companies input performance data on pipeline systems and then adjust an algorithm to match the characteristics of the infrastructure. The software ranks sections of pipe based on performance. The companies’ engineers study those rankings and decide on which sections of pipe to replace.

“These systems are getting better and better,” Bridgers said. “Now, with the appropriate due diligence, problems rise quickly to the surface and become the highest priorities among replacement activities.”

Operators employ a number of techniques to help manage the system – minimizing the chance of an incident – while implementing a thoughtful risk-based replacement strategy, Traweek pointed out. In the end, natural gas utilities are regulated by state utility commissions, which balance the need for investments in infrastructure to provide safe, reliable service while ensuring affordable energy bills for customers and fair returns on equity to attract capital at reasonable costs.

“The low price of natural gas has helped, and will continue to keep natural gas affordable, while the infrastructure is being modernized,” Traweek said. “It is the perfect environment for enhancing safety.”

Natural gas utilities spend over $19 billion annually to enhance the safety of delivery systems, government records show. This amount will increase as public utility commissions (PUCs) approve additional accelerated replacement programs.

While all natural gas utilities upgrade infrastructure using risk-based integrity management programs, 38 states have implemented rate mechanisms that foster accelerated replacement. In the case of those 12 without such programs, several either have annual rate cases or no longer have cast-iron pipelines in their systems, while maintaining only small amounts of bare steel.

Cast-Iron Incidents

PHMSA regulations require gas distribution operators to submit incident reports when a leak causes a death, injury, property damage in excess of $50,000 or the release of more than 3 million standard cubic feet of gas.

Incidents reported for 2005-13, not including those beyond the customer’s meter, yielded the following PHMSA data:

• 10.5% that occurred on gas distribution mains involved cast iron. However, only 2.5% of distribution mains are made of cast iron.

• 38% of cast- and wrought-iron main incidents resulted in injury or death, compared to 20% of incidents on other types of mains.

• The frequency of incidents involving cast-iron mains is more than four times greater than for mains made of other materials, based on total miles.

Regulators have long been aware cast-iron mains, which came into use in the 1830s, are more dangerous than new ductile iron pipe, or pipelines made of polyethylene plastic pipe or steel.

Still, there are those in the industry who believe cast-iron infrastructure is in many ways more reliable than either Aldyl-A (black plastic) pipe, installed in the 1970s and 1980s, or bare-steel pipe.

“Bare steel, in my opinion, is of a higher risk than cast iron, but for the PUCs and the average person there is no way to effectively convince them of that,” said Bridgers. “Trying to, I think, is a waste of time.”

Bare steel rusts in unpredictable locations and to the point that it no longer performs. As a result, when tracking bare steel, companies often find early indications of potential trouble such as light leaks. Since most bare steel is under higher pressure, once the corrosion has gotten through the pipe, a leak is detectable.

At that point the hope is that the leak has not occurred in a location that will cause a potential safety risk. In its favor, though, bare steel is much less susceptible to earth movement because it is not brittle.

Future Of Replacement

Beyond cast-iron and bare-steel replacement, engineers and consultants have pointed out that Aldyl-A pipe can create problems over time due to brittleness. Typically, these are smaller pipes of 2 inches or less, prone to breaks caused by earth movement. Polyethylene pipe used today is much more flexible than the early plastics.

Many in the industry believe most, if not all, cast iron will be removed from companies’ systems over the next 10 to 30 years, with bare steel and wrapped steel removal following; however, the timeline on that is more difficult to project.

Brittle plastic is mostly found in service lines that are more easily disturbed by landscaping activities than is bare steel, which tends to be buried in rights-of-way and protected by pavement above it. The service lines, Bridgers said, represent more risk over time.

“In my opinion, the transmission systems are already getting into pretty good shape,” he added. “In the coming years, the replacement efforts will move toward distribution transition, away from the Kinder Morgans, the Williams, the Spectras and on to the PG&Es, Piedmonts, the NiSources.”

Thormeyer pointed out that from NARUC’s vantage point, “Overall, the distribution systems are quite safe,” which is no small feat when one considers about 85% of the nation’s entire pipeline network consists of distribution lines – nearly every mile of which is inspected by state regulators.

“We all recognize, though, that this work is never done,” Thormeyer said. “We need to broaden our outreach efforts with the public to make them aware of their responsibility to call the 811 service before doing any excavation and 911 if they smell gas in their house.”

* An explosion involving an 8-inch cast-iron gas main owned by ConEd killed eight people and injured at least 70 May 12 in East Harlem. A preliminary report by the National Transportation Safety Board showed “small gas leaks below the pavement” caused the accident. The cause of the leak has yet to be determined, but safety officials said a broken water main may have been a contributing factor. The pipe was installed in 1887.

** An explosion involving a 12-inch cast-iron main break killed five people and destroyed eight homes Feb. 9, 2011 in Allentown, PA. The Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission cited UGI for failing to repair a leak discovered in 1979 within “a reasonable amount of time.” UGI was fined the maximum $500,000 and ordered to remove all of its cast-iron pipe within 14 years and all of its bare steel pipelines within 30 years of the February 2013 ruling. The pipe was installed in 1928.

By Michael Reed, Managing Editor

Comments