May 2014, Vol. 241, No. 5

Features

Methane Leaks: An Industry Challenge In A Carbon-Sensitive Age

A combination of environmental and safety concerns elevated in recent years has made the chase to corral and eventually eliminate methane leaks from the nation’s natural gas infrastructure a budding crusade.

Toss in the still-new phenomenon of the United States fast becoming a net exporter of fossil fuels and their byproducts, and the industry faces new challenges on an age-old problem.

Studies vary, but all point to an increased amount of time, money and attention to the so-called “fugitive” methane – not to be equated with “lost-and-unaccounted-for (LAUF)” gas – that oozes from the world’s most comprehensive infrastructure for producing, treating, storing and transporting natural gas. (LAUF is essentially an accounting difference between inflows and outflows of gas in the system.)

Universities, states, professional organizations and the industry have all weighed in on the subject in recent years, portending successes and the kind of continuing tough questions only more technology and resolve will answer.

Near the end of 2013, Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper unveiled what he called “first-in-the-nation” statewide rules to better detect and reduce methane emissions from the state’s booming oil and gas drilling. His goal is to make the industry the “cleanest, safest in the country,” preparing for even bigger future growth of the industry in Colorado.

Elsewhere, the University of Texas completed an industry-backed study in 2013, concluding that companies had begun to reduce leaks in the production process at wellheads, but there was still a large amount of work to be done reducing methane leaks from valve controllers and other equipment in the field. Environmental representatives and other climate change advocates seized on the study to say more needs to be done. Some in the industry have echoed this cry.

The leading baseline for tracking U.S. methane emissions, the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions inventory, last year reported some good news for the natural gas industry, noting estimates of leaks from the nationwide gas system were revised downward 33% to 143.6 metric tons (MMTe) in the latest calculations from 215.4 MMTe in 2010.

“Methane released from natural gas systems, which include field production, processing, transmission pipelines/storage and distribution, accounted for 2.2% of all U.S. GHG emissions in 2011,” according to the American Gas Association’s (AGA) analysis of the latest EPA data.

“The trend in the United States is a reduction of GHG emissions, and the EPA report does a good job in recognizing the reductions by the industry,” said New England-based Paul Armstrong, director of business development at the Gas Technology Institute (GTI).

The gas production area is a major source, and EPA is pushing “green [well] completion techniques” to cut emissions. There has been a lot of success so far with those improvements as documented in the University of Texas work.

Most recently, in early March a new analysis commissioned by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and written by a Fairfax, VA-based research firm, ICF International, concluded that methane emissions from U.S. oil and gas onshore operations can be economically reduced up to 40% of projected future levels in 2018. ICF estimated the cost of these reductions could be less than a penny/Mcf of gas produced. The 40% could equate to $100 million in annual savings for the U.S. economy and American consumers, according to the ICF report.

Earlier this year, the scientific journal, Science, examined “Methane Leakage from North American Natural Gas Systems,” concluding that organizations, including the EPA, have generally underestimated U.S. methane emissions overall, including those attributed to the natural gas industry. There are definitely continuing questions that arise about whether an accurate baseline is in place to test the results of mitigation measures going forward.

ICF offered caveats on its own work, based on the fact that it had to rely on the debated 2011 EPA analysis of emissions that was based on many assumptions and some older data sources. Thus, the ICF work labeled that data as “imperfect.” It also noted emission mitigation costs and performances are “highly site-specific and variable.” Thus, the values ICF assigned to those costs were estimated average values. The warning: measuring methane emissions is not an exact science.

In late March, the Obama administration released its methane strategy as part of the president’s climate change action plan, originally articulated in a speech at Georgetown University in mid-2013. Much anticipated by EDF and others in the environmental community, the strategy outlines steps and a timetable for reducing methane emissions from the oil and natural gas sector and other sources. The timetable runs through 2016 and drew praise from the industry and environmentalists alike.

Don Santa, CEO of the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America (INGAA) indicated the pipeline industry plans to work with the administration to further reduce emissions from the nation’s pipeline system.

“We continue to seek new and innovative technologies to target and reduce leaks and capture gas released or vented from the pipeline during testing, maintenance and repair activity,” he said.

The American Gas Association officials had a similar reaction, indicating that while emissions from their members’ pipeline systems are “in a declining trend,” gas companies are “not resting on their laurels” and intend to do more.

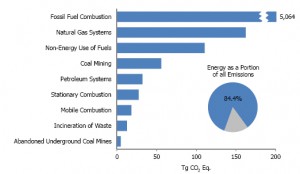

U.S. methane emissions have been broken down into five principal sources along with an “other” category that amounts to 10% of the total. The oil/natural gas industries combined account for 30%; livestock waste and naturally occurring sources represent 23%; landfills belch out 17%; coal mining provides 11%; and manure management represents 9%. Within oil/gas, 59% comes from the production phase of the business; 25% from transmission/storage; and 16% from the gas distribution utility sector.

Efficiency, like safety, is a driver in the methane leak reduction efforts, and GTI operates a Carbon Management Information Center that is designed to “fairly and objectively” parcel out various efficient natural gas and propane systems that can improve total system efficiency and reduce GHG emissions.

At INGAA), activity remains fairly robust on the methane emissions issue since a leading source of the unwanted emissions is centered on compressor stations, compressors and related equipment crucial to moving gas around the continent.

An INGAA environmental manager who has followed the issue, Lisa Beal, told P&GJ that there continues to be a lot of ongoing work aimed at further reducing methane leaks, but there never will be zero-emission solutions. Some of the leaks in the transmission system value chain are needed for safety or processing reasons, she said, adding that the reductions can come from one or more of three areas – technology advancements, ongoing compression research and use of best practices.

An ongoing collaboration among a half-dozen INGAA member companies, the EDF and Colorado State University is field testing the companies’ transmission and storage facilities, and analyzing the resulting new field data with two years’ worth of statistics from the ongoing EPA inventories. A report is expected to be made public soon, said Beal, who added there won’t be any “needle-movers” in the ongoing work and further reductions likely will be gradual.

“There has not been a lot of work done in the area of methane reduction, per se. A lot of the work has been done in the area of measurement,” Beal said. “Not every reduction opportunity is applicable across-the-board to all companies, so that’s why you have to look at the EPA Star Program examples with that perspective.”

Established in 1993, the Natural Gas STAR Program is supposed to be a flexible, voluntary collaborative that encourages oil and natural gas companies globally to adopt proven, cost-effective technologies and practices that improve operational efficiency and reduce methane emissions. Given that methane is the primary component of natural gas and is a potent greenhouse gas (21 times more powerful than carbon dioxide in trapping heat in the atmosphere), reducing methane emissions can result in environmental, economic and operational benefits. The STAR program attempts to unlock those benefits in models others can follow.

Natural Gas STAR partners have operations in all of the major gas industry sectors (production, gathering and processing, transmission, and distribution) that deliver natural gas to end users. Program partners represent 60% of the natural gas industry in the United States.

A major focus of the pipeline sector is on compressor stations, and for that the Virginia-based Pipeline Research Council International (PRCI) is leading the charge through one of its six standing committees, each representing a segment of the pipeline transportation space. In this case, PRCI’s Compressor/Pump Station Technical Committee is addressing the methane emissions issue, regarding the compressor stations and the individual compressors.

Gary Choquette, senior program manager for committee, said the ongoing research of compressors is linked to emissions reductions that are tied to the regulation of formaldehyde and other aldehydes.

“We’re doing a lot of work around building algorithms for doing engine diagnostics, similar to the ‘check engine’ light on your car,” Choquette said.

But the committee’s research agenda also is related to what Choquette called anti-reliability and integrity-related issues with compressor pump technologies. These include issues such as avoiding over-pressures and accommodating pressure spikes.

Generally, the emphasis is as much on safety and operating efficiency as it is on the environment, Choquette said, adding, “The environmental is a big part, but it goes beyond that, extending operating ranges for equipment to meet emissions across a wider operating range.”

PRCI’s compressor/pump station committee research is sometimes equipment-specific down to a particular engine make and model, Choquette said. But it also sometimes addresses other aspects of compressor station operations such as security, training, design, and emergency shutdown (ESD) systems.

It’s a continual search for better technology and best practices in a dynamic environment. An overarching goal, according to Choquette, is to maintain regulatory compliance while reducing and minimizing air emissions.

He said there are now wider swings in heat content and supply flows in the U.S. gas system because of increased gas-fired power generation and its inherent large demand swings, along with the increased amounts of shale gas production. That, in turn, has had an effect on efforts to curb methane emissions because it upsets the efficiency of compressor station equipment. There is more fluctuating content in the gas supplies with the large amounts of shale gas being mixed in, Choquette said.

“Some of the compression equipment was originally programmed for a specific Btu, so because of the wide variations [in heating value], the equipment needs to be de-rated to handle the higher heat-content supplies, and we’re trying to come up with solutions to more dynamically adjust the controls to accommodate more varied heat contents,” he said.

In the heart of the robust Marcellus Shale gas play, Pennsylvania has been wrestling with the proliferation of drilling and compressor stations in recent years as it struggles to measure overall emissions from its greatly elevated oil and gas production and transportation activities. The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has been issuing hundreds of permits over the past eight years related to compressor stations and dehydration units.

As with other states where the shale boom has hit, Pennsylvania monitors a mix of pollutants, including volatile organic compounds, nitrogen oxides (NOx), formaldehyde and GHGs. Stakeholders, however, readily acknowledge the state lacks a comprehensive monitoring program, particularly in the rural areas that are now being inundated with shale oil/gas operations. Much of the increased scrutiny by the state is tied to the proliferation of compressor stations in the various shale plays.

Historically, there were no comprehensive attempts to quantify the gas industry’s contributions to methane emissions until a joint EPA-Gas Research Institute (GTI’s predecessor) study in the early 1990s. It was what Armstrong called “a snapshot in time” of emissions volumes across the value chain of distribution, transmission/storage, and production. It established the baseline emission factors that are the basis of the data being reported to EPA currently, said Armstrong, who noted the industry only recently began to rework and enhance the factors established more than 20 years ago.

“We want to increase the quality and the precision of the numbers being used to better define the problem and pinpoint where the biggest sources are and to put programs into place to reduce emissions,” he said.

GTI is concentrating on the distribution sector in its part of this work, collecting more data under a multi-phase project that is taking a separate look at plastic and cast iron and unprotected steel pipe systems.

“We also are developing a methodology for calculating methane emissions that will provide a greater level of accuracy,” Armstrong said. “We will be working to launch an enhanced approach that would enable operators to use utility specific emission factors [EFs] based on their own leak data, instead of the national EFs, to more precisely define their emissions profiles.”

While industry and environmental officials remain preoccupied on mitigation and lowering methane emissions, equally important are the efforts to more accurately measure, quantify and establish a baseline methane emissions profile from which progress is measured. No shortage of brain power is evidenced in this regard, since many of the nation’s major think tanks are engaged in developing more highly sensitive methane-sensing technologies.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Los Alamos National Laboratory has a public-private collaboration ongoing that eventually will lead to a clearer understanding of fugitive methane emissions. “A significant part of understanding man’s role in global climate change is the accurate measurement of the components,” said Manvendra Dubey, a Los Alamos researcher heading the collaborative effort with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Rocky Mountain Oil Testing Center, and Chevron Corp.

On a global basis, there is a website (www.globalmethane.org/) for the Global Methane Institute (GMI) dedicated to reducing methane emissions through a voluntary, multilateral partnership. It is attempting to “advance the abatement, recovery and use of methane as a valuable clean energy source.”

GMI aspires to create an international network of “partner governments, private sector members, development banks, universities and nongovernment organizations.” That network is supposed to “build capacity, develop strategies and markets, and remove barriers” to establishing projects for methane reduction in partner countries.

As the scope of the effort broadens and becomes more refined, the challenge, whether on a macro- or micro-basis, is to merge the parallel safety and environmental efforts. They both call for new and better ways to identify and measure the sources and volumes of methane leaks that continue to bedevil an industry and an entire assortment of policymakers, activists, regulators and environmentalists.

It’s a somewhat thankless task, but the researchers and data collectors think progress is being made.

Richard Nemec is a Los Angeles-based correspondent for P&GJ. He can be reached at rnemec@ca.rr.com.

Comments