September 2014, Vol. 241, No. 9

Features

Oil Boom In North Dakota: Putting On A Happy Face

As part of a record-setting industry meeting in May at the Williston Basin Petroleum Conference in North Dakota, Republican Gov. Jack Dalrymple offered a keynote speech with one superlative after another about his sparsely populated, but energy- and agriculture-rich state. It seems his state is leading the nation in a number of categories these days, including having the happiest residents.

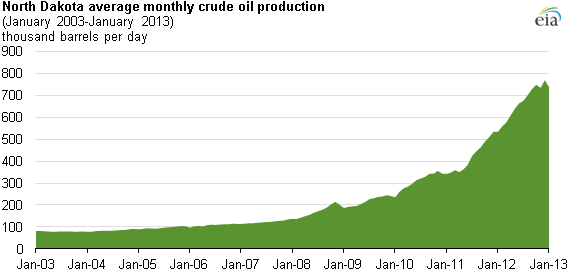

Perhaps the happiness, as defined by an anonymous national polling organization, is a reflection of the fact that this year North Dakota has the lowest unemployment rate in the country and the fastest growing economy. That, in turn, reflects an area of the United States where the growth in infrastructure generally, and in energy specifically, has been struggling to keep up with demand for ever-more oil and natural gas. For the pipeline and related businesses this represents both a blessing and a whole series of challenges.

Dalrymple told the eclectic audience of more than 4,000 locals and energy professionals from more than 40 states and seven countries that just like oil, natural gas is a “big story” in North Dakota. Evidence of that can be found in the all-out state/industry efforts to reduce flared associated gas. Those efforts have assumed the level of a governor-led crusade with a relentless stream of engineers and roustabouts trying to put the right infrastructure fixes on the nagging problem.

Nothing is simple in the Bakken. The glaring successes and stunning growth that have exceeded the expectations of even the most bullish of the industry and state officials have resulted from continuing solid technological advances and dogged focus on efficiency in all parts of the field operations from spudding to completions at multi-well drill sites. Fracking techniques, drilling efficiencies and the myriad of well completion techniques have all continuously improved in recent years.

“The volume curves [for output] just continue to strengthen as the producers get more experience with the play and continue to drive efficiencies,” said Kevin Burdick, Oklahoma-based ONEOK Partners LP’s vice president for gas gathering and processing. For a midstream company servicing all of this robust production, Burdick acknowledges that dealing with landowners and obtaining crucial rights-of-way can be a challenge.

ONEOK is on the front lines of the battle to curb flaring of associated gas at the wellhead by putting in place crucial takeaway infrastructure or well site options for burning the gas productively. The mix of challenges varies greatly from one part of the Williston Basin to another, Burdick said. The different mitigating measures pursued – and there are many, according to many industry players – all have to account for the distinctive production profile found in the Bakken, including a very large amount of natural gas liquids (NGL), richer in liquids than other crudes, and the technology improvements that are driving fracking and production results, but with negligible advances in technology specifically to curb flaring.

The next big advance in the Bakken involves the advent of multi-well pads, and that has huge implications for companies like ONEOK in planning for the right mix of infrastructure to handle clusters of wells up to a dozen a pad. In the midst of this shift and the state’s effort to get control of the flaring issue, new requirements that began in the summer have forced more timely communications between the midstream providers and the producers, according to ONEOK’s Bakken team.

“There’s more efficiency and an ability to better plan when these [multiple] wells are going to come online,” said Christy Williamson, ONEOK’s director of gas acquisition and the company’s representative on an industry task force in North Dakota that worked with state officials to create the ongoing accelerated get-tough-on-flaring campaign. “We’re now better aware of where these new wells are going to be, and certainly their size.

“That’s the other big change we’re seeing,” Williamson told P&GJ during the Williston Basin conference in late May. “Operators are no longer drilling the whole acreage for production; they’re moving to the multi-well pad phase, so if there are going to be a dozen or more wells in a spacing unit, planning far in advance for that is critical. With our 6,500 miles of pipelines [in North Dakota] only a couple of thousand of those miles were built in the last two or three years. There is a lot of legacy pipe that is probably too small for these larger, multi-well pads.”

In addition to the traditional gathering and processing infrastructure development that is still trying to keep up with record-breaking production growth, a host of small-scale technology breakthroughs have surfaced in recent months and years covering well site-sized fertilizer, liquefied natural gas (LNG) and gas-to-liquids (GTL) processing plants using the associated gas as its raw material.

In early June at the GTL North America Conference in Houston, a New Jersey-based start-up, Primus Green Energy Inc.’s George Boyajian, vice president for development, hawked his company’s proprietary technology for building modular, movable plants for producing a form of low polluting gasoline from natural gas.

Boyajian, with a doctorate degree from the University of Chicago, described a system that has both economic and technological harmony to satisfy the needs of everyone from royalty holders to regulators to producers that is now threatened with potential production interruptions, if the company can’t come up with viable gas capture plans to satisfy the state.

Financially backed by Israel Corp., one of the 10 largest companies on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange, Primus Green has successfully tested its technology with a pilot plant in Hillsborough, NJ and it expects to break ground on the large commercial facility later this year in the United States. Meanwhile, the firm is talking to several interested operators in North Dakota where the nation’s flaring issue is most acute.

Noting there is customization that has to be designed for each well site, depending on the quality of the gas at that particular site and whether pre-treatment would be required and the proximity of utilities, Boyajian said, “If we take an average plant, we expect to have one built in a year from the time of order.

“Traditionally, GTL has only been commercially viable on very large, multibillion-dollar plants, so what we have done here is achieve a breakthrough in economies of scale where we can make this very cost-effective on a small scale. No one has been able to do this before.”

Boyajian said Primus’ edge so far is the result of a very good spread between the cost of the raw material (natural gas) and the finished product, along with what he calls “very good engineering.” It has produced a “very efficient, cost-effective, low-capital cost plant” that is a first, not just in North America, but globally, he said.

The application in North Dakota would either be finished gasoline – some of which would be used in oil and gas operations, but the bulk of which would have to be transported to market – or it could be some other NGL transported to market via pipeline, truck or rail, along with the Bakken crude oil supplies, Boyajian explained. “It would come off the pad, we would stick it in with the crude, and off it would go.”

Below the pay-grade of state-elected leaders, on the ground in the Williston Basin, where Bakken crude oil and gas have turned ranchers into prosperous energy barons, people like Enbridge Pipelines Inc.’s Paul Fisher wrestle with the two-part challenge of continuing to put pipe in the ground while also building trust with a larger American public that has grown skeptical about the safety of the nation’s energy infrastructure. Through Fisher’s role as vice president for regional pipelines, Enbridge carries out integrity digs, using so-called smart pigs to test and maintain the safety of existing lines.

“We’re looking to detect any hairline cracks in pipe and also pick up indications of any corrosion that may be occurring on the inside of a pipeline,” Fisher said.

Using the data from the electronically sophisticated robotic devices going through pipes, Enbridge decides which pipeline segments need to be dug up and subjected to more thorough integrity management steps.

Having done about 500 digs in the Williston recently, Fisher has less than a half-dozen more to go. In each case, a 55-foot pipe segment is dug up and subjected to close scrutiny and testing, and in some cases replacement. The protective coating is removed and the steel pipe in sandblasted, followed by visual inspections. Often there is also ultra-sound technology and laser scans employed to determine exactly what the cracks look like and how severe they may be.

In the event there is substantial corrosion or cracking, the pipeline is shut down, and the defective segment is replaced. In North Dakota, Fisher said this job involves 16-gauge steel pipe, about a dozen people, including a state safety inspector, and costs on the average about $300,000.

In addition to a multibillion-dollar safety and maintenance program for all of its facilities stretching beyond the Bakken, Enbridge has served as a model of the shale plays’ unprecedented growth, increasing its oil transportation capacity in North Dakota from less than 100,000 bpd to more than 450,000 bpd through a series of design, expansion and technology moves that Fisher outlined with much relish.

“Through various means and low-cost expansions we have been able to increase the capacity of the North Dakota system,” said Fisher. “The capacity expansions came from short-looping of pipe, introducing drag-resistant agents to allow the oil to flow much more freely and changing the system from a batch-operated system to one that is a common stream.”

The pipe work has been completed by building a rail facility for that added option for moving Bakken light sweet crude. Eventually, Enbridge plans to expand rail capacity beyond its current 80,000 bpd, and the mainline that has a 200,000-bpd capacity would also be enlarged as part of the Bakken expansion project.

Another example of the more traditional infrastructure project that takes on enormous importance in the context of North Dakota’s boom is Enbridge’s Sandpiper oil pipeline expansion project, which increases the takeaway capacity of the Calgary-based pipeline company’s North Dakota system by 225,000 bpd, taking it to a total throughput of 580,000 bpd. The expansion involves construction of a 374-mile, 24-inch pipeline from Beaver Lodge, ND to Clearbrook, MN and a 238-mile, 30-inch pipeline from Clearbrook to a mainline system terminal in Superior, WI.

“Sandpiper will essentially loop our mainline North Dakota system, but rather than tie in with the mainline in Clearbrook, we’re going farther south so that Bakken crude won’t be confined – it will get into the Superior Hub from which there are multiple paths, enabling it to go to a greater number of markets,” said Fisher, noting the expansion is planned for completion in March 2016, including the design, construction and commissioning of four pump stations and seven tanks.

After the post-winter thaw and just before he kicked off the Williston Basin conference, Dalrymple found himself about 200 miles northwest of the state capital in Tioga, helping Hess Corp. mark completion of the much-anticipated expansion of a gas processing plant that eventually will more than double its capacity from 100 MMcf/d to 240 MMcf/d.

“This expanded gas plant will not only help reduce the flaring of natural gas, but it will add value to this abundant resource and create additional markets for natural gas produced in North Dakota,” Dalrymple told the news media and dignitaries gathered by Hess officials.

The project is part of a more than $1.5 billion infrastructure investment made by Hess between 2012 and 2014 in North Dakota that the company maintains has significantly increased production of propane, methane, butane and natural gasoline, as well as created the ability to produce ethane, a vital industrial product that previously had not been produced in the state.

The expansion also brings a marked improvement in efficiency and reduces the amount of gas flared at Hess’ operations, according to the Houston-based energy giant.

Hess began designing the expansion of the Tioga plant in 2009 and transitioning to its expanded capacity in late 2013. At the peak of construction, there were about 1,400 people working on the site. The facility now employs about 100 full-time workers and 40 contractors. After several weather-related delays, it ramped up to full capacity earlier this summer.

Hess Corp.’s operations in North Dakota date back to 1951 when the Amerada Petroleum Co. first discovered oil in North Dakota at the Clarence Iverson #1 well near Tioga. In 2013, Hess was producing an average of 67,000 bpd from the Bakken, operating 722 wells, and investing more than $4 billion in Bakken Shale development.

In recognizing the new gas takeaway infrastructure, Dalrymple told those assembled at the plant opening that Hess has almost daily opportunities to invest elsewhere in the United States and around the world. For him, the fact that they have poured billions of dollars into North Dakota speaks volumes about what’s ongoing in his state’s expanding oil/gas patch.

At various levels, there are hundreds of other energy sector players doing similar things to build an infrastructure in Williston Basin that seems limitless at this point in time.

Richard Nemec is a Los Angeles-based correspondent for P&GJ. He can be reached at rnemec@ca.rr.com.

Comments