January 2015, Vol. 242, No. 1

Features

LDCs Can Profit From Natural Gas Role In North American Energy Mix, Economy

Local distribution companies are the most essential ingredient if natural gas is to become the predominant energy fuel in North America. Although strong inroads have already been taken, a number of challenges remain before the LDCs can take their rightful place in the natural gas value chain.

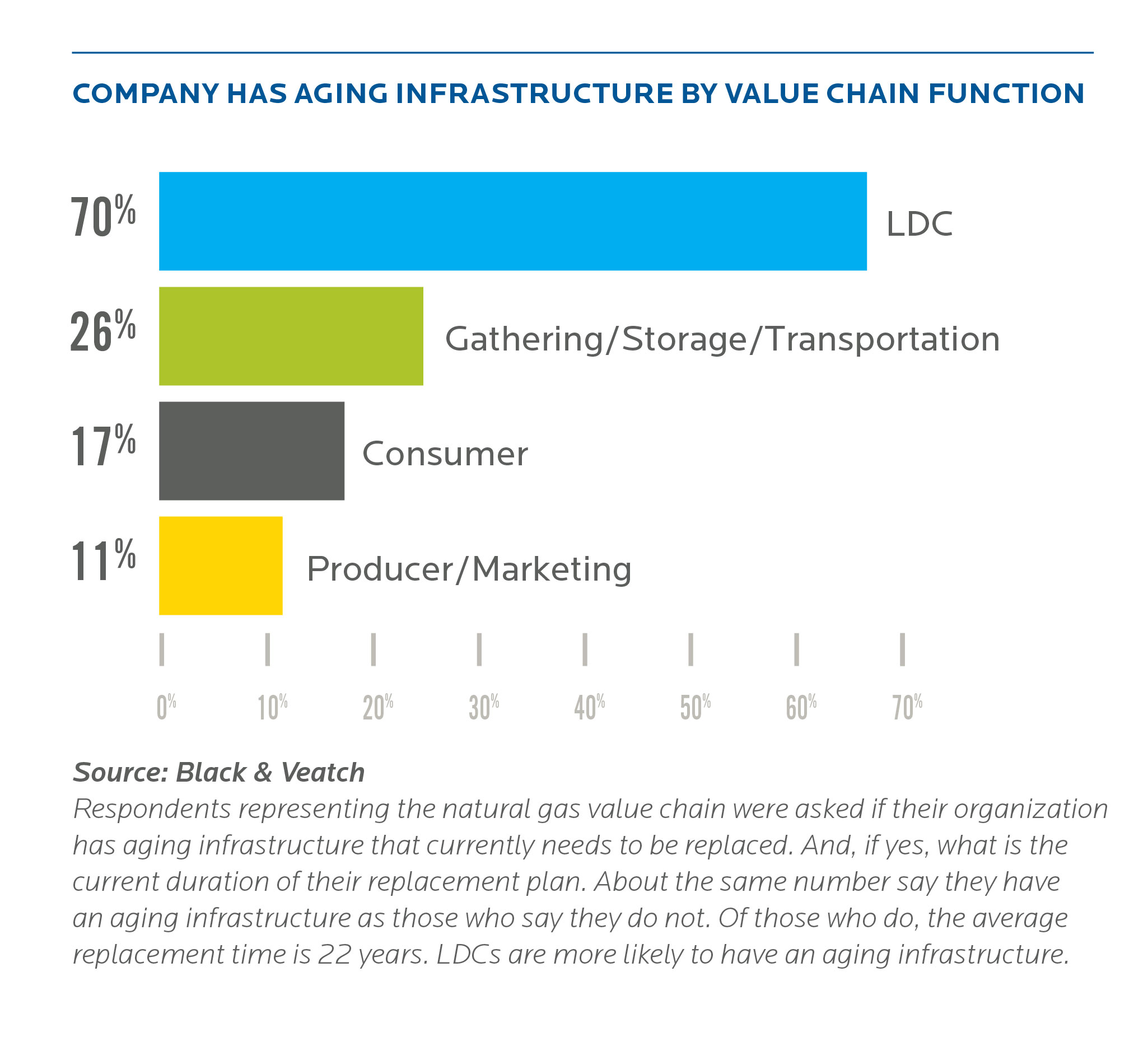

They need to continue to improve the safety of their aging delivery systems and are doing so through prudent integrity management practices. But they also must remain sensitive to the environment, particularly in minimizing lowering fugitive gas emissions from their systems. In the United States, LDCs account for approximately 2 million miles of pipelines, a number that is continuing to go as natural gas supplies are made available to more parts of the nation.

In this article, British-based FC Gas Intelligence interview s three experts involved in the natural gas business: Susan Fleck, Vice President, Gas Pipeline Safety and Compliance, National Grid; James Marston, Vice President, U.S. Climate and Energy, Environmental Defense Fund, and Joel Bluestein, Senior Vice President, ICF International.

Though they represent different interests, there is consensus that natural gas offers great potential for society at large, if the right steps continue to be taken.

Susan Fleck is Vice President, Gas Pipeline Safety and Compliance at National Grid, an international energy company based in London, UK. She is responsible for development and delivery of all gas compliance improvement initiatives, and tracking and monitoring gas compliance across the firm’s U.S. business. She works directly with all state and federal regulators that govern gas pipeline safety. Fleck holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Civil Engineering from Carnegie-Mellon University and an MBA (Finance) from the Carroll School of Management at Boston College.

Q: We’re seeing environmental drivers on gas LDC businesses increasing in strength. What are the key drivers behind National Grid’s efforts to reduce fugitive methane emissions?

Fleck: It’s interesting because National Grid’s number one driver has always been, and will continue to be, enhancing safety and reliability. We’re taking a lot of action to eliminate older infrastructure by accelerating the replacement of leak-prone materials – the older cast-iron materials and bare steel. A great added benefit is that those are the pipes that leak the methane. As we accelerate our replacements, we’re also accelerating our reductions of methane emissions. We came at it from a safety and reliability perspective, but we get these great benefits around emissions too.

The public is generally more interested in emissions from natural gas. It’s becoming a hot topic. As a result, we have aligned with a lot of the organizations that are trying to understand those emissions better. It’s helping us understand how our replacement programs and overall strategies can interweave with the emissions reduction interests the general public have.

Q: What roles do policymakers have to play on the methane issue? And what direction do you see policy headed on this issue?

Fleck: We’re regulated by three states (New York, Rhode Island and Massachusetts) and several federal agencies. If you look across the U.S. you’re going to see different perspectives in different regions.

In the Northeast, where we have a large amount of this leak-prone cast-iron and bare-steel infrastructure, the policymakers are very interested in our strategies around managing those older systems. What I’m getting from our regulators and policymakers is that they’re interested in replacing them, as we’re doing, to fix reliability issues. They’re interested in managing the leakage until those systems are replaced, which means doing targeted repairs. It takes time to get them all replaced. And they’re interested in any other actions we can take to reduce the amount of emissions from our normal, everyday operating practices.

Here’s an example: when you’re doing certain kinds of work on the system, you have to get the gas out so you can work on it safely. That’s generally done by blowing that gas into the atmosphere. They’re anxious for us to find ways to do that work without venting any gas into the atmosphere. They want us to replace our systems quickly, to repair leaks in the meantime, and to take other actions to reduce emissions from our system all the time.

Essentially what we need from them is to understand how that can impact our rate-making proceedings. We have to get permission to do many of these things from our regulators, so we’re looking for more certainty from them on what kind of programs are going to be approved. We want to make sure that we can fund these projects going forward without too big an impact on the customers who ultimately pay the bill. It’s a tricky business!

Q: What regulatory program elements are necessary for natural gas utilities to proactively reduce methane emissions while maintaining safety and reliability standards?

Fleck: We have to collaborate with our rate-making authorities to build replacement programs that don’t impact customers so much that they can’t afford to pay. We have to work with them to make the programs more certain so that we can attract investment dollars at the right kind of market rate to do these gigantic programs. At the same time we also have to attract a workforce to do this extra work, and ensure that the manufacturers are setting out to create the right amount of materials, pipes and valves. That won’t happen until the manufacturers know there’s certainty that these programs will be continuing so they can plan for the future.

Workforce planning is also where we could get some help from regulatory programs. We need to attract and retain a much bigger workforce. We’ve got many retirements coming up in the next couple of years – the workforce is aging rapidly. At the same time, we’re putting these big replacement programs into place. That’s a big issue for us so any help we can get around that would be greatly appreciated.

Q: What are some of the ‘next-gen’ technologies that have been deployed at National Grid to find and detect leaks, and how these are performing for you?

Fleck: We’re doing some research on a couple of fronts. The main one that we’re looking at is Cavity Ring-Down Spectroscopy (CRDS). This is a new detection technology. It’s a very sensitive new leak-detection technology. Some of the other companies in the country have already deployed it. It has the capability to detect leaks from a vehicle – you mount it on top of a vehicle and you can detect methane over a pretty large distance around you. It will allow us to find leaks more easily and more quickly. We’re doing research on it to make sure if it really is finding pipeline leaks and not other kinds of methane, and on the sensitivity of the instrument.

We see a bright future in using that kind of technology. It can also help us validate how much gas is leaking from a given leak, and use it to prioritize which leaks to repair.

A second technology is lining methodologies for our older mains. That means inserting, within an existing leak-prone main, a sleeve or liner that is tighter and so leaks less. Until those pipes can be completely replaced with new materials, those liners or inserts can reduce leakage.

The third area is that, as I mentioned earlier, when you do work on your system you have to vent gas into the atmosphere. We’re looking at a technology called Blow-Down Compressors. They capture the gas that would normally be vented to the atmosphere, compress it, and put it back into the system downstream. That technology is big and cumbersome, but we’re trying to find a way to get it shrunk down so we can deploy more of them across our territory.

Fourth is all-around damage prevention. We look at any technologies that help us identify buried pipelines and structures so that they can be avoided, so that we can mark out our facilities more effectively for when others are digging in close proximity.

Q: What are some of the methane emission studies National Grid is involved with?

Fleck: We’re working with the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) on several studies. They’re running 16 studies across the nation to understand methane emissions across the entire natural gas value stream. We’re engaged with them on several studies.

One is to understand how much gas is emitted from a leak, whether we can actually measure that. That will feed into the emissions factors. We have to report methane emissions to the EPA. They have you report the number of miles of pipe you have of a particular material, and then multiply it by a factor which estimates how many leaks are along that mile of pipe and how much is leaking. We’re working with the EDF to create more accurate emissions factors.

The second study is the methane mobile mapping study, which you can find via Google. They used a device we discussed earlier over several cities and towns in the U.S. and physically identified on a map where they found methane leakage. We worked with them to help validate their data, and allowed them access to a couple of our communities.

The third study we’re working with the EDF on is a top-down measurement study where they’re actually sampling the atmosphere – not at the ground level, but higher in the atmosphere, and trying to understand how the methane leaking from our systems, from agriculture and every other possible source, can end up in the atmosphere.

We’re also working with the Gas Technology Institute (GTI) and NYSEARCH on several studies looking at these emissions factors – we’re looking at how to deploy methane mobile-type technology to do winter leakage patrols, how methane degrades over time, and working on developing a methane detector for residential use.

Q: What are some of the key challenges facing National Grid’s infrastructure replacement program?

Fleck: The first is the customer challenge. This means increasing rates because we have to invest in these replacement programs. It also means big disruptions in service while we replace the pipes on their streets. There’s also communications and how we keep them informed on what we’re doing and how we’re doing it.

Next we have the community. The community is where we operate, where we have construction work happening. We have to work hard with the communities to coordinate permits, get police protection and have paving replacement for our planned work. They have to face complaints coming from the community about the disruption while we’re doing the work. These are big challenges especially for smaller communities where much of their staff is part time. If we go into a town and replace a couple of miles of pipe, it can be a real struggle for those areas.

Then there are regulatory challenges. We have two different groups of regulators. First there are those that deal with the rates customers pay and balance what work is needed with the customer’s ability to pay. That’s very difficult for them. Then there are the regulators looking at the safety side. They have to inspect and oversee all of the construction activity happening across their territory. They do third-party assessments of all the work going on. As we increase that workload it increases their workload.

For company challenges, we have to manage safety risks while we’re making replacements and that means monitoring, finding and fixing leaks. We have to develop and deliver constant rate filings, going to every state in which we operate, talking to them about what we’re doing and how we’re doing it so they can make decisions on our rate requests. We have to raise the capital to fund all these programs.

We have to recruit, hire, train, qualify and retain a lot more workers. We require materials, equipment and vehicles. We have to coordinate our work with all the cities and towns, and communicate effectively with all of these different stakeholders. With all of this, working with natural gas we have the added challenge of safety.

Q: How are you going to overcome the workforce development challenge at National Grid?

Fleck: We’re doing a deep dive within our company to look at our existing workforce and make some estimates around attrition. We’re doing an integrated work plan looking at our increasing workload going forward, and developing a very firm estimate of how many additional, incremental people we’ll need to meet the new load.

We’re trying to understand exactly what skill sets we’ll need going forward for engineering, management and fieldworkers. When you look at the field workers, we need qualified welders, fusers, pipefitters and plumbers – the whole nine yards.

Our plan is to then go to local community colleges within our service territory, to work with high schools and trade associations and try to give them as much information as we can about what our needs are going to be over the next five years and work with them to help build curricula for training programs to help them develop a workforce for us.

At the same time, we have to step back and look at our learning and development organization internally, understand what kind of skills we’re going to be getting from these new employees, and essentially rebuild our training programs from the ground up to ensure we have the right programs, materials and trainers to bring to this large number of new employees in and get them qualified to work on a dangerous product like natural gas.

We have to think about the on-boarding process. How long is it going to take us to hire someone right out of high school and get them trained and qualified and get them the right amount of work experience to make them effective in the field on their own?

This is a huge deal for the industry, particularly in the Northeast where every company is facing an ageing infrastructure problem. We’re looking to external organizations to see if anyone else can help us with that – organizations like the Center for Energy Workforce Development (CEWD). They’re working with electric, gas and nuclear utilities to help build the workforce, career awareness and education.

We’re also working with the American Gas Association and the Northeast Gas Association, seeing if we can partner with neighboring utilities, and working closely with the contractor community to give estimates of what kind of capabilities we’re looking at. They’re making efforts to see how they can on-board some people and build up their own workforce. This is the challenge that’s going to cause us the biggest problems. The real roadblock is going to be finding enough qualified workers to actually do the work. Companies are potentially going to be fighting for the same limited pool of people and we’re going to struggle.

James D. Marston is Vice President, U.S. Climate and Energy, at the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). He is the founding director of the Texas office of Environmental Defense Fund, where he has served since 1988. He is also a leader of the Pecan Street, Inc., a partnership aimed at making fundamental changes in the nation’s electricity grid.

Q: Can you describe the Environmental Defense Fund’s work and priorities on the methane emissions issue?

Marston: There is a big boom in oil and natural gas drilling in the U.S. sometimes called unconventional oil and gas, other times called shale oil and gas. There is no doubt this has great economic benefits. The question is, can we capture the potential environmental benefits from this newly freed-up source of oil and gas?

Our efforts are to deal with the reality of this big boom. The question for us is can we minimize the local impacts on communities and landowners while maximizing the climate benefits of methane over coal as a boiler fuel, and for other uses? The key to that is preventing methane leaking along the entire supply system. Methane is a very potent greenhouse gas. Depending on the time frame, it’s 27 to 70 times more potent on a per-ton basis than carbon dioxide. We’re working hard to both understand the extent of the leaking methane and figure out ways to reduce that amount dramatically.

Q: President Obama directed the EPA to evaluate the best ways to reduce methane emissions from the oil and gas industry as part of the White House methane strategy. How significant was that announcement?

Marston: It’s a very important announcement. Frankly, it ought to be one that is embraced by both industry as well as the states that have oil and gas operations. We need to have the public behind drilling, but the public is not going to support large-scale increases in oil and gas drilling if their local communities are harmed, if it’s making local air pollution and the climate problem worse. Part of the deal ought to be that we get the potential climate benefit from natural gas, but we need to have regulations that deal with the fact that there are unnecessary leaks of methane from the system.

Q: How would you describe environment impact of methane leakage?

Marston: You always need to be comparing natural gas with what it’s replacing. You have more than one use of natural gas. One is as a boiler fuel. The carbon dioxide that comes from burning coal is roughly twice as much per megawatt hour as that produced by burning natural gas as a boiler fuel. But because of the potency of methane, if a little over 3% of the methane is leached out of the system between drilling and burning it in the boiler, then the climate benefits of reduced carbon dioxide emissions are lost. So the key is keeping loss levels below the 3.2% level, where coal and natural gas have roughly the same impacts on the climate.

The problem in the U.S. – and around the world – is that nobody has really done any serious measurements of where it is leaking and how much is being lost. We have undertaken a series of studies, 16 in all, with universities and industries to find out the amount that is leaking and how we can reduce those leaks.

Q: There has been much debate about the climate implications of increased natural gas usage. Natural gas burns cleaner than other fossil fuels, but how much does methane leaking during the production, delivery and use of natural gas undo much of the greenhouse gas benefits we think we’re getting when natural gas is substituted for other fuels?

Marston: The number right now is probably less than 3%. The EPA has an estimate that is probably a little too high, and industry has a number that is probably a little too low. We’re still gathering the data, but what we think it will show is that while there are some benefits of natural gas over coal right now, it will be very easy to reduce that number in half, down to near 1%, and maybe even less than 1%, with some smart investments.

The good thing about this situation is that what they’re leaking is product. And if you’re leaking product as opposed to waste, then the cost of capturing it is partly offset by the additional methane you have to sell.

With regards to the local distribution companies, it’s not so much the comparison of coal to gas, but the fact that we have in some places unnecessarily been leaking more natural gas than we need to. We’re still getting the data, but it appears to be more of a problem with older infrastructure. Cities like Boston are losing a lot more methane than newer cities in the Southwest, for instance.

In the U.S. local distribution companies are regulated monopolies, and get a return on investment of their capital cost. So interestingly enough, the companies often want to replace pipe. Regulators and consumer groups also want to minimize that amount because it drives up the cost of natural gas. The good news is that new equipment is allowing companies to target their pipe replacement.

Traditionally what they do is replace the oldest pipe first, which is not irrational, but not as good as replacing the pipes that are leaking first. So we are undertaking efforts in California, New Jersey and some other states to change the regulatory paradigm to use these great new leak detection technologies and focus pipe replacement dollars on giving the best return on investment in terms of reducing methane leakage.

Q: What action does the EDF want to see from LDCs specifically on the issue of methane leakage?

Marston: The midstream part of the gas industry needs to reduce their emissions as well as local distribution companies. We have several LDCs doing some joint studies with us on where the methane is leaking in the distribution system, and how much. The first thing is, once these studies are out, all the companies ought to learn the lessons of these studies.

They ought to voluntarily, or be required, to use the new remote sensing equipment to better target where the leaks are occurring, and they ought to replace those areas first. I hope they join with us in advocating changes at the state regulatory agencies to reward them for replacing pipelines that reduce the biggest leaks of methane.

Q: What sort of methane emissions regulations will be necessary to support the LDC industry in reducing fugitive methane emissions?

Marston: Number one, they ought to get paid for investing in this new remote sensing equipment, and be required to use it. They ought to then be required to identify and map where the largest leaks are, and be required to put their dollars into those areas. In the end we ought to mandate that they spend the dollars on replacing pipeline and not on the basis of replacing the oldest pipes first, but on replacing the pipes that are leaking the most first.

Q: With the California Public Utilities Commission’s SB 1371, California is arguably leading the way in legislation to help prevent gas leaks from LDCs systems. Will the necessary legislation come at the state level or is a national approach needed?

Marston: Almost certainly this is going to be a state level effort. LDCs have traditionally been regulated at the local level. This is a national and international issue. If the states don’t follow the lead of California and get more aggressive about reducing leaks from the LDCs, it may be necessary for the federal government to come in, because this is a big greenhouse gas issue and we’ve got obligations to do our part to reduce climate change.

Q: More regulations could mean an increased cost for LDCs. Will incoming regulations make natural gas less cost-competitive?

Marston: There’s so much gas that the price is very low, and near historic low levels. If there are some additional costs to prevent the leaking of methane then it will still mean that natural gas is a very low-priced fuel. But what one has to remember is that what is being captured by preventing leaks from pipelines, and repairing other places where there are leaks, is product. It makes the economics work well. There probably is a positive return on investment. Those costs will be largely offset by having more product to sell and wasting less.

Joel Bluestein is Senior Vice President at ICF International, a management, technology, and policy consulting firm based in Fairfax, VA. An expert on the effects of environmental and energy regulation, at ICF he has been directly involved in most of the recently developed emission trading programs. He holds a degree in mechanical engineering from MIT.

In this interview Bluestein discusses CHP which stands for combined heat and power. As promoted by the EPA “the CHP Partnership is a voluntary program seeking to reduce the environmental impact of power generation by promoting the use of CHP. The Partnership works closely with energy users, the CHP industry, state and local governments, and other clean energy stakeholders to facilitate the development of new projects and to promote their environmental and economic benefits.”

Q: What is the scale of the opportunity CHP offers gas LDCs in terms of being an avenue for growth?

Bluestein: The Obama administration has set a goal of 40 GW of new CHP for the US. So that’s a pretty big target. Not all of it would be LDC-based – some of it would be industrial load that is not focused on LDCs. But even a small piece of that would be pretty significant for the LDC market.

Residential natural gas demand, even with population growth, has not been growing because of improved efficiency in residential appliances, and to some extent a demographic shift toward areas with a lower heating load. New markets are critical for LDCs and CHP is one of only a handful of fundamental new markets that can provide growth to LDCs.

Q: What are the key benefits of CHP to natural gas utilities?

Bluestein: First, it’s one of the few really new markets that are available, and second, it’s a good load factor. You don’t want loads that are highly variable, that create stress on the system. A high load factor, or base-load demand, is great for LDCs. It’s applicable to a lot of different markets, whether commercial or small industrial, institutional or education – it can fit in a lot of places.

Q: What are the key drivers for CHP development in the U.S.?

Bluestein: CHP has gone through multiple phases in the US. Much of the development has been for large systems, which in the 1980s and 1990s were driven by regulations that incentivized very large systems. Changes in the market structure have now made those drivers superfluous. The focus now is on efficiency. CHP is the most widely available and readily applicable source of efficiency for power and thermal generation that we have.

It’s always all about the economics, and in the right application CHP can be a very cost-effective and beneficial technology for end users, which then creates value for the LDC.

Q: What trends do you see in terms of CHP and how can gas LDCs capitalize on these trends?

Bluestein: There are a few things. Of course one is the shale gas revolution. It’s much more widely accepted now that we have a large, stable supply of natural gas in the U.S, which has led to lower gas prices, but more importantly, to confidence from consumers that prices will stay moderate, and that there will be a good supply for as far ahead as we can see. This had led to a resurgence of industrial growth in the U.S. that we wouldn’t have predicted 10 years ago. So there are new industrial gas users, and in general, much more comfort with investment in gas technology. That’s a key factor.

As I mentioned, at the federal level there has been an executive target for increased CHP and many states as well have focused on CHP as an important energy efficiency technology that’s part of their energy portfolio standards, or they’re offering incentives for the development of CHP.

Another one is from the power side – the congestion and transmission limits that are leading to people looking for alternative ways to provide electricity in congested urban areas, which can be done through distributed generation, and most economically, through CHP. So there are several drivers that we’re seeing.

Q: What are the challenges facing gas utilities & CHP development?

Bluestein: The biggest challenge to any energy efficiency technology, and maybe even more so for CHP, is the market inefficiencies related to energy efficiency. Yes, it has a good payback, and yes, it’s economically beneficial when you do the math, but customers have other things on their minds.

They may have other investments they want to make. CHP pays back, but it has an upfront capital cost. And that capital cost has to compete with things that may be closer to the heart of the consumer – a new process or a new product, redecorating the restaurant, or a new building for a university. There’s always limited capital and CHP has to compete with other investments. Depending on how forward-looking the customer is, and how willing they are to invest in alternative technology, that can be the largest barrier.

Q: One challenge facing LDCs is that much of the CHP installed today is connected directly to the interstate natural gas pipeline rather than the network maintained by the LDC. In light of this, where should LDCs focus their efforts in encouraging CHP to reap the benefits?

Bluestein: Especially during the 1980s and 1990s, which was the largest growth period for CHP, there were very large industrial projects multi-hundred megawatt projects. Those tended to connect directly into the transmission network but they were driven by the regulatory drivers of 30 years ago.

Today we’re seeing a different world where there’s much more interest in the commercial and institutional markets. That means hotels, resorts or office buildings, and institutional meaning universities, hospitals or military bases. They tend to be smaller, and much more of the size that would connect through the LDC. That change in the market is much more beneficial to the LDC suppliers than the transmission suppliers.

Q: What regulatory and policy changes could help LDCs better identify & enjoy the benefits of CHP?

Bluestein: Some states are actively promoting CHP for its environmental benefits as well as the benefits of supplying electricity in congested areas. There are a variety of policies being provided as incentives for CHP. These can include environmental regulation of the CHP that better recognizes its environmental benefits. There are direct incentives for CHP such as capital cost buy-downs or rate incentives. Also, there is ensuring that the electricity rates are not biased against on-site generation. All of those things can help encourage the use of CHP.

These interviews first appeared in an FC Gas Intelligence report. FC Gas Intelligence is organizing a conference covering these issues – the Gas Utility Summit 2015- March 2-3 in San Francisco. For more information, visit the conference website: http://events.fc-gi.com/gas-utility-summit/ . Pipeline & Gas Journal readers can get a $250 USD reduction in the pass price using the discount code PGJ1214.

Comments