November 2015, Vol. 242, No. 11

Features

Latin America Forced to Face Growing Supply-Demand Gap

Latin America’s prominence on the world gas stage has increased over the last several years. Although it is well-endowed with natural gas resources, the region has struggled to find its footing as both a natural gas producer and consumer. Consequently, Latin America’s potential as a natural gas import province is the topic of increasingly animated debate.

Potential upstream investors, midstream infrastructure developers, and the financial and legal institutions keen to support the development of Latin America’s hydrocarbon supply and distribution all have a vested interest in understanding its role in the global gas business of today and tomorrow.

But even in this day and age of instant communication and online research resources, the acquisition of knowledge about Latin American gas markets is not easy. This is attributable to several factors, such as language barriers and the generally opaque nature of many Latin American countries’ natural gas businesses. Public domain information on the structure and dynamics of regional and country-specific gas industries may be limited or difficult to obtain.

Without the benefit of personal contacts within the national hydrocarbon companies and energy regulatory bodies, it is difficult for outsiders to form an understanding of individual countries’ gas industries, let alone the regional picture. This, in turn, limits the ability to form a truly global view of the natural gas sector.

To address these issues, Nexant plans a multi-client study to profile and assess the current and future natural gas markets in Latin America. The study will forecast regional gas trade flows, with an emphasis on the region’s existing and future LNG-importing countries.

Competitive Terms Lacking

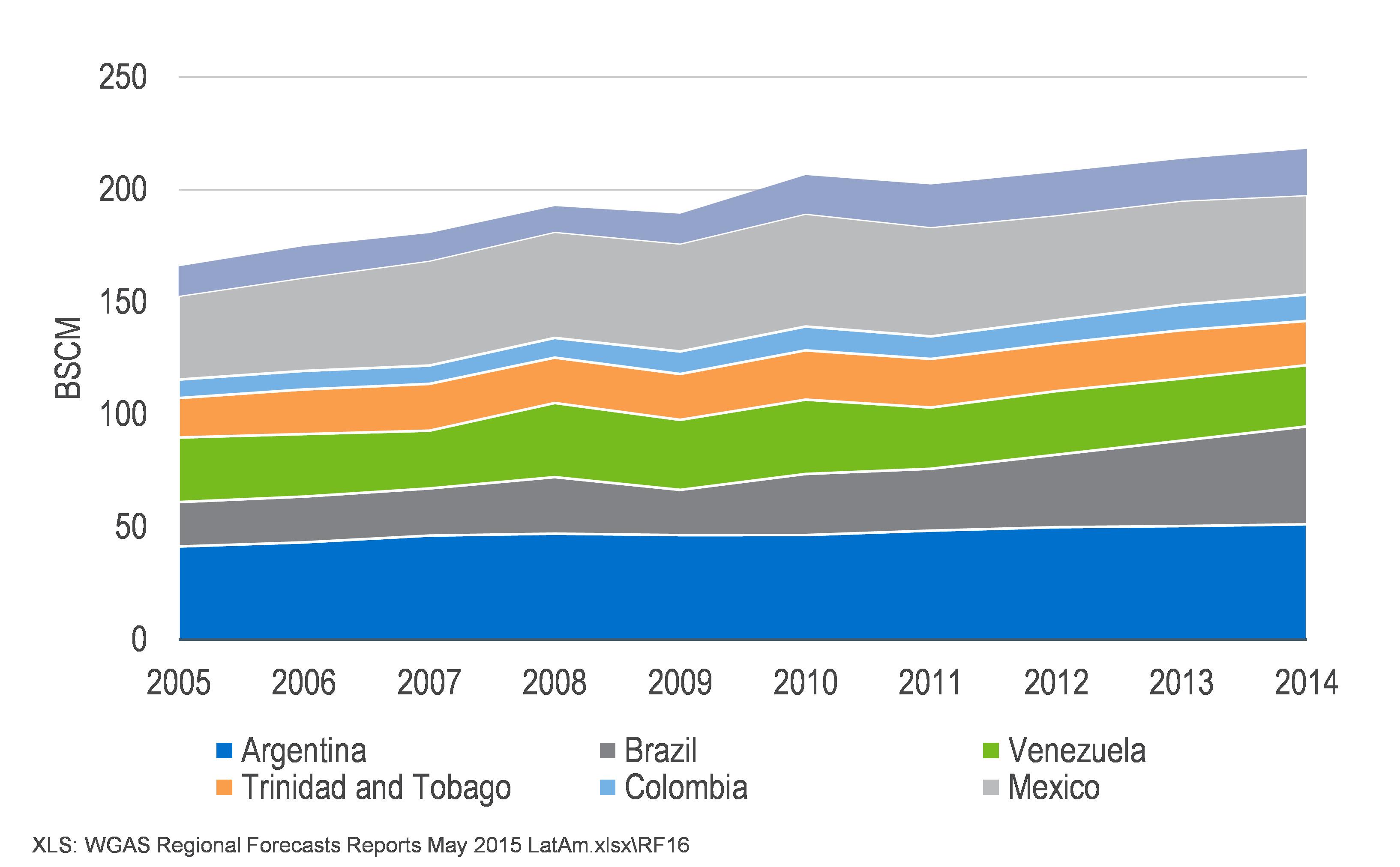

A gap between indigenous natural gas output and consumption has emerged in some Latin American gas-producing states in recent years. Although the region’s overall production has grown over the last decade (Figure 1), only a few countries such as Peru and Venezuela have remained self-sufficient in natural gas.

Others like Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico have struggled to produce sufficient volumes to meet demand. In the past, various factors like the indifferent pace of energy market reform and an emphasis on oil production adversely affected natural gas production in some Latin American countries. Adding a further layer of complexity has been the struggle to attract outside investment to gas sectors, especially the upstream.

Not all Latin American countries have offered investors competitive terms and provided the requisite regulatory and fiscal certainty, especially regarding the sanctity of existing contracts. Consequently, natural gas production in parts of Latin America has struggled to keep up with demand – a demand that has in many cases been stimulated by artificially low end-user prices. Economic expansion and the intermittent availability of renewable power-generation sources are other factors supporting demand growth, especially by the power sector.

Due to the growing indigenous supply-demand gap, certain Latin American countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico are increasingly dependent on imports. At the other end of the scale are Central American and some Caribbean countries with no indigenous production and limited access to imports.

Pipeline gas imports have been the traditional source of external supply for several Latin American countries if geography, geology and geopolitics allow for it, but this is not always possible:

• Insufficient gas to fulfil export commitments – Traditional pipeline gas exporters like Argentina have been unable to sustain export levels due to the mismanagement of its natural gas industry as a whole. In addition to its inability to continue pipeline exports to neighboring countries, Argentina was obliged to become an LNG importer in 2008. Brazil and Chile, which previously imported Argentinean gas via pipeline, also joined the regional LNG importers club at about the same time.

• Lack of proven reserves – Bolivia is a key regional pipeline exporter to southern Latin America, but its ability to boost exports is contingent on proving up more reserves at home and satisfying domestic requirements first.

• Lack of connectivity – New cross-border pipelines could “gasify” parts of Latin America that are isolated from existing supply sources. A regional Central American network similar to Sistema de Interconexión Eléctrica de los Países de América Central (SIEPAC), which is an interconnection of the power grids of six Central American nations, embodies this type of thinking. However, a host of issues have combined to keep the concept of an integrated Central American gas pipeline confined to paper. These include a lack of demand to justify such a costly initiative and a lack of consensus on key commercial and regulatory issues.

• Luck of geography – Not all Latin American countries are favorably located to interconnect with secure and abundant gas supply sources. Their neighbors may lack the gas reserves to comfortably export gas, or they may lack suitable terrain or cordial enough a cordial relationship with their neighbor to make such an arrangement feasible.

As a result, countries with growing gas supply-demand gaps have increasingly turned to external sources – that is, LNG – to make up the supply shortfall. This growing dependence is borne out by the numbers: Latin America’s LNG imports totaled 27 Bcm in 2014, up from less than 1 billion standard cubic meters (Bscm) in 2005 (Figure 2).

So keen is the need for LNG in some of the region’s countries that Argentina and Brazil have outbid top-tier Asia Pacific LNG importers for cargoes in recent years. Although countries such as Chile and the Dominican Republic have the security afforded by long-term supply contracts, importers in Argentina and Brazil have adopted a more opportunistic approach toward cargo procurement.

Until fairly recently, spot market LNG procurement took place against a backdrop of high oil prices, strong competition from Asia, and constrained global LNG supply. This resulted in record-high prices being paid for cargoes by certain Latin American buyers – prices that the domestic markets in these countries were ill-equipped to bear.

The emergence of Latin America as an LNG import province and its ability to occasionally compete with east of Suez buyers is a significant development in the global LNG business. Existing and prospective global LNG suppliers have taken note: Latin America has been targeted by potential sellers in areas as diverse as the United States and East Africa.

Taking into account the challenges facing Latin American gas production in the face of growing demand, especially in the key countries of Argentina and Brazil, regional buyers will be seeking new deals on LNG. Going forward, Latin America’s role in the evolving global LNG marketplace will be a topic of great interest for competing LNG buyers, as well as to sellers west and east of Suez looking for new market opportunities.

What Next for Latin America?

Looking ahead, natural gas will be increasingly favored throughout Latin America as a power-generation fuel and industrial feedstock. Even Latin American countries that emphasize the importance of renewables in the energy mix can stand to benefit from natural gas: thermal power generation is a reliable source of energy, whereas climate chaos may affect weather-dependent sources of power production, such as rainfall for hydropower generation.

Although the outlook for increased natural gas demand is fair, optimism must be tempered with the knowledge that investor confidence in the energy regimes of some Latin American countries is not strong. If this lack of confidence prevails, the prospects for new domestic gas projects will be adversely affected, with a knock-on effect on overall gas consumption.

On the supply side, Latin American natural gas production is expected to satisfy the bulk of regional demand requirements. A contributing factor to the robust gas demand outlook is the expectation of significant production growth in the key countries of Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and Venezuela.

Argentina is believed to have significant unconventional hydrocarbon resources, and there are hopes that additional exploration will enable the nation to echo, although not replicate, the shale gas production success in the United States. Meanwhile, Brazil’s pre-salt deposits in the Campos and Santos basin have been the focus of great interest and investment, and are already contributing to Brazil’s indigenous gas supply-base.

For its part, Mexico is optimistic the energy reforms instituted in 2014 will attract the foreign investment needed to increase its gas production base. Not surprisingly, all these optimistic gas production forecasts have resulted in ambitious domestic gas use plans in the host countries. There are also high hopes the region’s overall gas import dependence, especially LNG, will eventually fall on the back of higher gas production.

However, production outlooks are always subject to a degree of uncertainty, and the challenges facing Latin America as a gas-producing province are not insignificant. Wild cards affecting the outlook for gas production include disappointing drilling results, difficulty attracting sufficient investor support, uncertain regulatory regimes, a lack of confidence in regional national petroleum companies and high break-even costs for new sources of production.

If future production falls short of expectations, the region’s LNG import dependence may continue – and possibly grow. The failure of Latin America’s indigenous production plans to materialize as planned may result in one of three outcomes: a greater-than-expected reliance on imported gas, a longer-than-expected reliance on imported gas or a combination of the two.

This could affect investment plans in the region’s power-generation and industrial sectors, and the price of gas for commercial and residential end-users. For downstream players hoping to launch gas use projects based on abundant, reasonably priced indigenous supply, the failure of indigenous production sources to materialize and the consequent dependence on possibly costly imported gas would be cause for concern.

Although intraregional pipeline imports will remain an important part of the gas supply mix for certain Latin American countries, the roster of regional LNG importers is expected to swell over the next few years: Colombia, Cuba, El Salvador, Panama and Uruguay all have LNG import plans in various stages of maturity.

This raises questions about potential supply sources for existing and future Latin American LNG importers. Intraregional LNG flows (Trinidad and Peru) will continue to satisfy the bulk of Latin American demand, according to Nexant’s proprietary World Gas Model, but the United States will play an increasingly important role after 2020. Thanks to surging unconventional gas production, projected U.S. natural gas supply will be sufficient to underpin a large export sector, with deliveries to customers via pipeline gas and LNG.

The Panama Canal expansion could further foster a diversity of supply and lower the cost of natural gas, in particular from Trinidad and Tobago or the U.S.-to-Pacific markets. Once the expansion is completed, the majority of the world’s LNG tankers will be able to pass through the canal, both opening Asian markets to Latin American natural gas producers and expanding landing options for Central American countries on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

Nexant’s proposed study “Latin America as a Natural Gas Province: Getting Acquainted with the Great Unknown” is targeted for completion at the end of the fourth quarter.

Editor’s note: For the purpose of this article, Nexant’s definition of the region encompasses Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

[inline:nexant_figure2.jpg]

Figure 2: Latin American regasification throughput (2005-2014).

[inline:IMG_1068.jpg]

Author: Nelly Mikhaiel is a senior consultant with Nexant’s Energy and Chemicals division. She has 15 years’ experience as a natural gas consultant, with a focus on LNG. Mikhaiel earned both her bachelor of arts and Ph.D. degree at the University of Western Australia.

Comments