April 2016, Vol. 243, No. 4

Features

Canada’s Energy Industry, Part II: Globally Focused Growth Projects

At the beginning of 2016, Calgary, Alberta-based midstream developer and operator Veresen, Inc. had $1 billion invested in two gas-processing facilities under construction in the prolific Montney shale play in parts of British Columbia and Alberta. In giving guidance on a conference call just before the New Year, Veresen CEO Don Althoff made clear these new infrastructure endeavors were just the beginning of other major projects to follow on both sides of the U.S.-Canada border.

Industry and business think tanks have projected 2016 as the pivotal year for decisions on Canada’s next major buildout of energy infrastructure. Final investment decisions are due for some of the largest and leading liquefied natural gas (LNG) proposals, including Pacific Northwest LNG and the Canadian-Asian joint venture embodied in LNG Canada Development Inc. But whether on a macro-basis energy production and development can remain roughly 5% of the nation’s economic growth engine was being debated at the outset of the New Year as global energy commodity price headwinds were getting stronger in early 2016.

In January, an analysis from the global consultant/research firm, IHS predicted a difficult year in 2016 for North American exploration and production (E&P) companies as their past strong hedging programs roll off and the prospects for continued depressed market prices grew more evident. Canadian E&Ps had just 9% of their production hedged at the start of the New Year (C$78.54/bbl for oil and C$3.58/Mcf for natural gas).

“For most companies in the sector, 2016 is going to be another very tough year, as plunging revenues lead to balance sheet deterioration and financial pressures mount,” said IHS’s Paul O’Donnell, author and principal analysts for the report, Comparative Peer Group Analysis of North American E&Ps.

The end of 2015 provided a muddled tableau of the New Year’s energy portrait in Canada as an LNG Canada-sponsored study by Navigant Consulting Inc. articulated a 380-year natural gas supply for that nation at the same time Canada’s new Prime Minister Justin Trudeau hinted at revisions in the nation’s energy policy that could cause restrictions on oil tanker traffic on the West Coast, off British Columbia. Initial reports caused Enbridge’s $6.1 billion Northern Gateway oil pipeline project-backers to take stock of their plans.

Then at the start of the New Year, Trudeau’s Liberal government unveiled a new political layer of national approvals for federally regulated oil and gas projects. New principles were outlined by the national natural resources and environmental ministers for future decisions on National Energy Board (NEB) and Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency decisions. This is an outgrowth of the Liberal Party, including regulatory review processes among the planks in its campaign platform that Trudeau ran on last year.

Even before the party won the nation’s elections last fall, political observers were crediting Liberal Party leaders with support for new energy infrastructure, including pipelines. But they qualified this assessment by noting these projects with the Trudeau government will need to gain the support of local and native communities. Environmental protections will be a key.

In response to Trudeau’s oil tanker traffic ideas, a representative of Northern Gateway quickly dismissed any speculation that the pipeline project could be in jeopardy, noting that the joint venture and various project proponents, including Aboriginal Equity Partners, “remain committed to this essential Canadian infrastructure.” Similar responses are being made for other approved and pending projects, all seen as additional “essential” new energy infrastructure in Canada.

Northern Gateway received its national governmental approval in 2014, following what spokesman Ivan Giesbrecht calls the NEB’s “careful examination, one of the most exhaustive reviews of its kind in Canadian history.” The company also has completed a comprehensive navigation review under what in Canada is called the Transport Canada TERMPOL review process, Giesbrecht noted.

“Since then, we have been very clear in stating that we have more work to do in establishing respectful dialogues and achieving improved relationships with First Nations and Metis peoples. We have made significant progress building support on the B.C. coast and along the pipeline corridor,” he said, adding at the end of 2015 that Northern Gateway hopes to sit down face-to-face with Trudeau and his cabinet to provide an update on the multibillion-dollar project.

The Shell consortium project, LNG Canada, holds an NEB license and final environmental approval to export up to 3.2 Bcf/d of LNG from Kitimat, B.C., but in February a final decision on whether to move ahead with the project was delayed “out into the future.” Nevertheless, Royal Dutch Shell CEO Ben van Beurden said at the time the company’s long-term goal is to have a diversified LNG portfolio to match the estimated 2.3% annual growth in gas demand worldwide.

TransCanada Corp.’s Nova Gas Transmission Ltd. (NGTL) is the owner of a gas transmission system known as the NGTL System. Nova is the big national intra-provincial gas transmission system in Alberta where it is investing about $2.5 billion over the next three years to extend its system to the Peace Region of the new shale plays in Alberta and British Columbia. It is located in the northeast corner of British Columbia between the Rocky Mountain foothills on the west and the Alberta Plains on the east. That’s designed to put NGTL into the deep part of the Montney play in British Columbia to bring on 2.5 Bcf/d in the Peace region.

Like Shell, however, TransCanada, in early February, put the brakes on some of its proposed pipeline extensions into British Columbia until more definitive plans are set for the development of the proposed LNG export facility at Kitimat. NGTL told the NEB it would suspend its pipeline project until the two principal shippers, Chevron Canada, Ltd. and Australian-based Woodside Energy International Ltd., set a new development schedule for the export facility.

“It is the deep part of the basin where you are getting all of the shale gas development in Alberta and B.C. both,” according to Mark Pinney, manager of natural gas markets/transportation at the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP).

Pinney pointed out that TransCanada/Nova also has the North Montney Project, a $1.7 billion pipeline underwritten by the Malaysian national energy company, Petronas. It plans to build one of the proposed LNG terminals on British Columbia’s West Coast.

“This is a really big project for Nova because it reaches deep into the Montney region of B.C.,” he said. It intends to connect with the Prince Rupert gas transmission system and then go to the LNG plant, moving up to a peak capacity of 2.5 Bcf/d. “It is also a critical part of the proposed debottlenecking in that part of the basin,” he said. The LNG project is called “Pacific NW LNG” with Petronas as its sponsor.

Pinney and others point to Canada’s potential 1,093 Tcf of natural gas reserves, for which advanced technology makes them economically recoverable in wells that can produce for 30 years or more. This potential has spawned numerous large and small infrastructure projects that cross from Alberta into British Columbia to the west coast and intra-provisional projects within British Columbia. Westcoast Pipeline reaches back into the deep Montney Basin with a 240 MMcf/d High Pine pipeline set for completion at the end of 2016, along with a second project in the same time frame, Jackfish Lake, a 140 MMcf/d line.

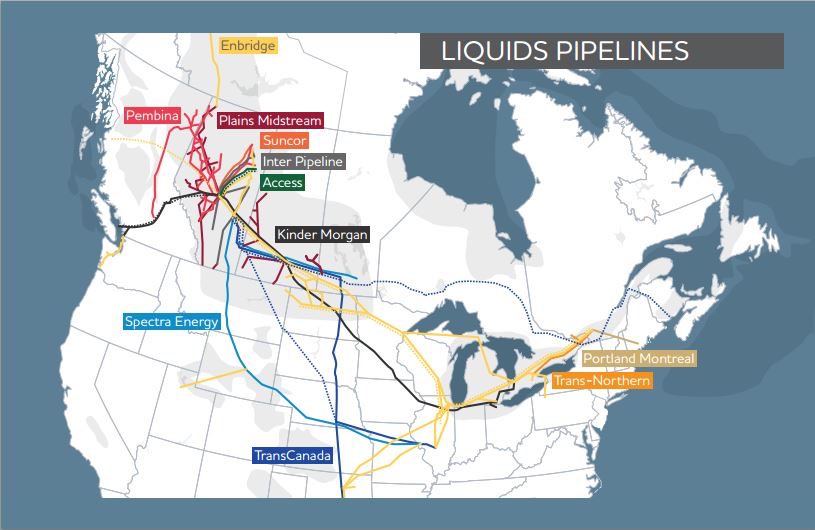

At the end of 2015, the Canadian Energy Pipeline Association (CEPA) launched a new interactive digital map showing detailed information about transmission pipelines is western Canada. The dynamic maps provide details on the age of pipelines, the companies operating them, oil and gas products moved in each line and who regulates each.

“Energy and the environment are something we’re all deeply concerned about, and the more information that’s available the better,” said Brenda Kenny, CEO of CEPA.

Some proposed LNG plans have affiliated pipelines, such as the $5 billion Prince Rupert project for a 560-mile system stretching across the mountains to the west coast of British Columbia. Second, there is the Shell LNG Canada project, which would be served by another pipeline – Coastal Gaslink, a $4.8 billion, 380-mile project. Upstream of the Coastal pipe project, Nova would have to extend its system over to bring Alberta gas across to the LNG plant. That is the $2 billion Merrick Mainline project put on hold in February.

Costs are driven by topography as much as the distances, according to Pinney, and in British Columbia the topography is challenging. If 7 Bcf/d East-West exports are eventually approved in Canada, what are the pipe requirements?

Pinney said there is about $60 billion of capital investment in liquefaction plants, if Canada allows the 7 Bcf/d export capacity. Then upstream there is another $15 billion in pipelines for the most likely three west coast plants. The industry is looking at over $70 billion in investment, Pinney said. But companies will have to spend money to produce the gas – drilling up to 220 new wells annually to keep 1 Bcf/d production, so that’s about $1.5 billion annually for each 1 Bcf/d of export capacity; upstream that amounts to about $10 billion in annual investment to support a 7 Bcf/d export capacity, according to CAPP’s calculations.

In some cases, potential new infrastructure work involves enhancing or changing existing pipelines and related equipment as CAPP’s Pinney noted. With more gas imports coming from the U.S. side of the border, there is the possibility for switching an existing gas pipeline to oil as part of proposals from TransCanada and others. “That would be part of an Energy East project to bring western crude oil to eastern Canadian refineries,” he said. “So there are opportunities.”

More challenging are the new greenfield projects, of which there seem to be an endless variety, mainly tied to the need to build facilities to meet the LNG export opportunity.

“I see less of a challenge for building natural gas pipelines than crude oil, but we are still challenged when you go through British Columbia’s terrain,” Pinney said, adding, capacity increases on existing pipelines are nearly always an option, too, through looping strategically.

There are also several First Nation issues with the native people who have claims to the lands being crossed. There are hardly any treaties in place to cover the building of pipelines.

“It is important for the pipeline proponents to get the First Nations people on their side as partners,” Pinney said. “The way the court decisions are going in Canada, the First Nations have to be consulted. They can make an assertion they have aboriginal title, so you may need consent from them as well as needing to consult with them. The prospects of litigation and uncertainty that come out of this is a challenge for infrastructure development in B.C. in particular.”

As the Conference Board of Canada was looking ahead at 2016, improvement over 2015 was on many smart minds, seeing growth in the household products and energy sectors, both of which their analysts see benefiting from lower crude oil prices and lower exchange rates with the nation’s biggest trading partner, the United States. Besides the big-ticket oil and gas projects, Carlos Murillo, an economist with the Conference Board based in Calgary, said he sees various land-based and barge-based small-scale LNG projects continuing to advance this year through various regulatory processes.

“There are various gas extraction as well as natural gas and NGL transportation projects in the works throughout western Canada,” he said. “Regulatory processes will continue for various export pipeline proposals, including the Trans Mountain expansion, Energy East and Northern Gateway projects. Four oil sands projects are expected to come online in 2016 with total capacity of nearly 150,000 bpd.”

Coastal GasLink Pipeline Ltd., a TransCanada subsidiary, is pursuing a new pipeline from northeast British Columbia to the province’s western coast to serve proposed export terminals. It is a 400-mile project from the Dawson Creek area to the coast, transporting gas to the proposed LNG Canada export facility near Kitimat whose fate was uncertain in the midst of the commodity price slump.

As with any energy project in Canada in recent times, Coastal GasLink has been subjected to environmental reviews, along with Aboriginal rights considerations, and landowner and other stakeholder input that carry considerable weight regarding the fate of new energy projects.

“The proposed route, as presented in our application to the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office, was determined by considering Aboriginal, landowner and stakeholder input, the environment, archaeological and cultural issues, land-use compatibility, safety, constructability and economics,” the Coastal GasLink website said.

This is a 48-inch pipeline, involving three metering stations and one compressor station. Its initial capacity would be 2-3 Bcf/d. Company officials tout the level of detail and concern given to the Aboriginal communities, landowners and stakeholders. “We shared information, gathered input, and incorporated feedback into our decision-making and route-refinement process.”

Another TransCanada project, Energy East Pipeline, bids to ship 1.1 MMbpd of oil from Alberta and Saskatchewan to refineries in eastern Canada, covering a distance of over 2,700 miles. The project involves converting a portion of the existing natural gas mainline to oil transportation, constructing new segments in six provinces, along with the related pump stations, tank terminals and marine facilities.

As a backdrop to all of the proposed infrastructure projects, business think tanks like the Conference Board of Canada continue to forecast cloudy outlooks for 2016 with improving conditions in subsequent years. The Conference Board’s gas industry outlook sees production and demand increasing, but profitability for companies declining in the near term.

“North American market conditions will remain the primary concern for Canadian natural gas producers through 2019, but LNG export developments will increasingly link Canadian producers to global markets,” the Board’s outlook from last year said. “Global demand for natural gas will continue to expand over the medium term, albeit at a slower-than-historical pace, consistent with revised global economic growth prospects.

“Demand increases will be driven by emerging economies, but North America will continue to be the largest regional natural gas market in the world. Across end-use sectors, power generation and industrial demand will lead increases in demand on a global basis. The price competitiveness of natural gas across regions and among different fuels will determine the success of natural gas in capturing a growing share of energy demand in the future.”

Much of the eventual energy growth in Canada depends on the natural gas industry finally becoming solidly global. That is where future growth lies.

“It is more and more important to understand the competitiveness of the Canadian gas industry,” the Conference Board authors said in their report last year. “The industry’s long-term growth prospects are tied to looking beyond the North American market.”

Richard Nemec is P&GJ’s West Coast Contributing Editor in Los Angeles. He can be reached at rnemec@ca.rr.com.

(Maps courtesy of Canadian Energy Pipeline Association)

Comments