April 2016, Vol. 243, No. 4

Features

New Opportunities Arise with Demand in Mexico

In the southern United States, Texas finds itself awash with gas while Mexico, its southern neighbor, has seen a decline of 24% in its domestic natural gas production since 2010 and is unable to meet rising domestic demand, according to a recent presentation by Kenneth S. Culotta, of the Houston energy law firm, King & Spalding.

Since 2012, Texas shale gas fields have been both the enablers and the chief beneficiaries of rising Mexican consumption of natural gas (Figure 1). U.S. gas exports to Mexico hit a near-record 70.9 Bcf last April, up 25% over the previous year, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). This upward trend is expected to continue, albeit at a slower pace, with Bloomberg forecasting U.S. deliveries to Mexico will reach 150 Bcf a month by 2020.

The growth in Mexican demand has provided a valuable opportunity for hard-pressed Texas gas producers experiencing a drop in Henry Hub natural gas prices from $3.48 MMBtu in December 2014 to $1.93 MMBtu in December 2015. In April, U.S. gas exports to Mexico accounted for 3% of production and may exceed 5% by 2030, EIA predicted.

In contrast, worldwide U.S. LNG exports, from the five export plants with sufficient customers on long-term contracts to guarantee revenues, are likely to exceed gas exports to Mexico by the end of 2019, according to energy analysts at Wood Mackenzie.

Rapid economic development and a switch from oil to gas-powered generation will account for at least 75% of the projected growth in Mexico’s natural gas consumption between 2012 and 2027. Private and independent power producers (IPPs) are expected to lead the way in gas-fired generation, with their demand for gas rising at an annual average of 7.9%, from 1.6 Bcf/d in 2012 to 4.9 Bcf/d in 2027.

By contrast, gas consumption by power plants belonging to México’s national energy company Comision Federal de Electricidad (CFE) will grow much slower at just 0.4% annually, from 1.1 Bcf/d in 2012 to 1.2 Bcf/d in 2027, according to Mexico’s national energy ministry, Secretaría de Energía de México (SENER). Much of the growth in demand for gas power stems from major cities, such as Mexico City, Guadalajara and Monterrey, and towns located in the western, northern and central regions.

To counteract declining domestic gas production and to help satisfy rising demand, the Mexican energy ministry liberalized the power sector and is actively encouraging significant public and private investment in shale exploration and production, looking to raise production from 5.7 Bcf/d to 8 Bcf/d in 2018, or 3.8% annually.

The Burgos Basin in the north, along the Mexican side of the Rio Grande, offers the best prospect since it shares in the same petro-geology as the Eagle Ford and Haynesville shale formations across the river. However, given costs of exploration and development in current market conditions of low prices together with the availability of cheap gas from across the border, development of Mexican shale gas is, at best, a medium-term play.

This is especially true given the absence of pipelines to carry gas away to markets and violence in the region. Added to which is the scarcity of water, which will require additional investment for fracking operations. Therefore, in the short and medium term, U.S. natural gas supplies will dominate the Mexican gas market, and it is this scenario that provides a huge opportunity for pipeline construction.

Pipelines Booming

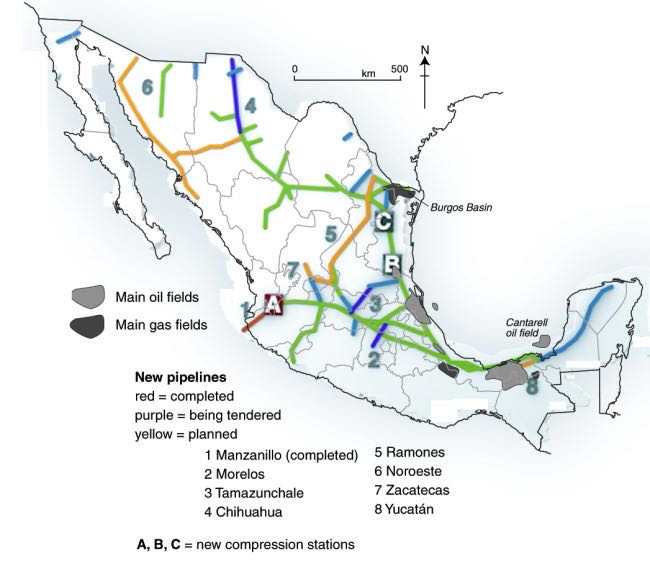

Much of Mexico’s existing 11,230-mile pipeline network is unable to accommodate the predicted growth in gas imports from the United States, let alone future development of the shale gas deposits in the country’s north. However, this should be resolved by 2025 upon completion of the $10 billion investment program covering 22 gas pipeline projects, the highlight of which is the 6,210-mile Los Ramones pipeline.

The pipeline’s first phase, completed at the end of 2014, connects central Mexico with Texas gas. Also easing access to U.S. gas are TransCanada’s construction and ownership of the El Encino-Topolobampo and the El Oro-Mazatlan pipelines in the northwest of Mexico. Scheduled to be in service in 2016, these open-access pipelines will connect U.S. natural gas supplies to key customers including the CFE and a fertilizer plant at the port of Topolobampo on the Pacific Coast.

By end of 2016, TransCanada’s total investment in Mexico will reach approximately US $2.6 billion. It is expected that once the current expansion pipeline projects is completed, at least 90% of Mexican shale gas prospects as well as centers of demand, will lie within easy reach of transportation facilities.

Another investment opportunity awaits with the proposed $3.1 billion, 800-km Texas–Tuxpan subsea pipeline. With a design capacity of 2.6 Bcf/d by 2018 (See Figure 3) it almost matches the export capacity of 2.7 Bcf/d of the first phase of Cheniere’s Sabine Pass LNG export terminal in Texas. U.S. and Canadian project promoters, who are relatively inexperienced in constructing extensive subsea pipelines, are likely to consult European subsea engineering contractors with experience in delivering subsea pipelines such as Nord Stream in the Baltic Sea or the Langeled Pipeline, in the North Sea.

Gas Storage

To ensure the new gas pipeline network is responsive to peak demand and for security reasons, complementary underground storage units are recommended. Natural gas storage facilities are inadequate, and Mexico only has 2.4 days of LNG storage capacity, compared with the average storage capacity for Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries of 83 days.

Energy law specialist Culotta noted the absence of any plans to develop significant underground storage facilities comparable to the open access gas storage facility at Bergermeer in Holland, with a storage capacity of 4.1 Bcm. Should Mexico’s Energy Ministry wish to participate in underground storage, agreeing on an optimal location could prove challenging. The Rio Grande border with Texas offers the best location geologically, while the Federal District of Mexico City is the best operational site, though unsuitable since it lies in a volcanic area.

Therefore, the fundamental question, according to Culotta, is which side of the Rio Grande would likely be favored by investors? North American investors naturally would prefer the known legal and business environment of the Texas side.

Future

At the moment, Mexico’s industrial users pay 75% more for electricity than their American rivals. Over the next decade, government reform and liberalization of the energy sector has opened the way for an injection of private domestic and foreign capital to build a power sector and pipeline distribution network to serve the needs of industry and inhabitants for decades to come.

The Mexican government’s five-year energy infrastructure plan, 2014-18, imagined an overall investment of $34 billion for building natural gas pipelines ($13 billion), a national power grid ($7 billion) and new gas power plants ($14 billion), the Wall Street Journal said in April 2014.

The boom in pipeline investment facilitating increasing imports of Texas gas, and a switch from expensive oil to cheaper gas generation will increase the competitiveness of Mexico’s industry. Additionally, once market conditions improve, the survivors of the Texas shale gas and oil downturn may take advantage of the opportunities waiting south of the border.

Further pipeline developments in Mexico will be needed as the effect of changing geo-economic logistics, the availability of U.S. gas and Mexico’s membership in NAFTA make it an increasingly attractive destination for manufacturers targeting the North American market. Reshoring, economic development, population growth and rising incomes make Mexico an attractive investment proposition in manufacturing, transportation and power.

Already, both American and Canadian pipeline companies, including TransCanada, Kinder Morgan and Sempra International, have shown interest in participating in Mexico’s future beyond the current five-year plan, ending in 2018, to construct an additional 20 domestic and cross-border gas pipelines by 2030.

By Nicholas Newman, Contributing Editor

Comments