December 2017, Vol. 244, No. 12

Features

Massachusetts Campaign Raises Voice in Turbulent Northeast

Alongside the gigantic Marcellus gas field, the nation’s priciest electricity market faces supply shortages as the industry searches for answers.

By Jeff Awalt, Executive Editor

What a difference a couple of decades can make.

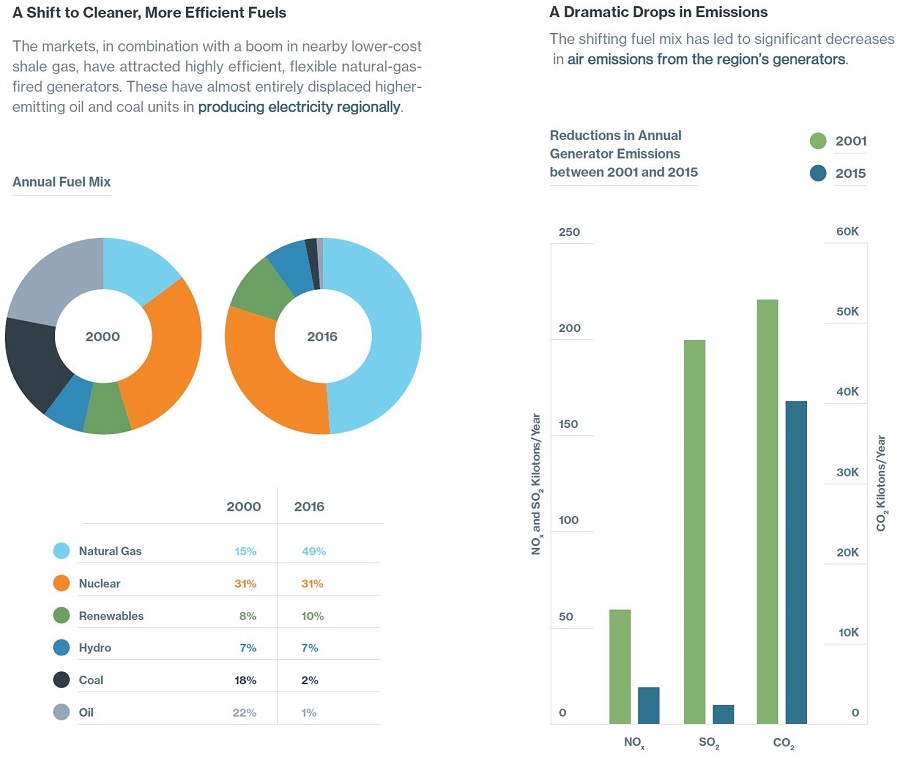

In the 1990s, Massachusetts environmentalists campaigned to replace coal- and oil-fired plants and generate more of the state’s electricity with cleaner-burning natural gas. Now that it fuels more than half of the Commonwealth’s growing electricity consumption, however, activists have declared war on natural gas and the pipelines that deliver it.

The “zero-carbon” movement has stoked protests elsewhere, but unique regional challenges and concerns of potential supply disruption in Massachusetts have prompted the Northeast Gas Association (NGA) to test a communications campaign here that it hopes may serve as a model for other regions.

Speaking Up, Reaching Out

“If you just watch media coverage in this region, you’d think that most of the people here don’t want any more natural gas,” said Thomas Kiley, president and CEO of the NGA. “In fact, there are many more people that want natural gas in their homes and businesses than there are out there protesting, but that message doesn’t get out. That’s one of the reasons why our member companies asked us to spearhead this awareness campaign.”

The NGA’s Energy Reliability Awareness Campaign seeks to build support for natural gas infrastructure expansion by teaching the public about its importance to the Massachusetts economy and its essential role in an electricity grid that increasingly relies on renewable energy sources.

Throughout the year-long program, NGA members and staff are working to expand media outreach through editorial briefings, article placements and business and community alliances. Working with key stakeholders and constituents, the NGA is advocating for a long-term energy strategy that balances the need for natural gas and renewable energy resources, including modernization of the gas distribution system.

By developing the goals and strategy for a proactive campaign, the NGA also positions itself to respond more quickly and effectively when pipeline opponents spread what it often considers to be misinformation through traditional and social media. In early October, for instance, the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) released a report suggesting some New England utility companies were reserving excess pipeline capacity on cold winter days in order to raise electricity prices. The NGA responded immediately with a bluntly worded statement that called the EDF’s analysis “profoundly misleading and inaccurate,” and its allegations “false and, frankly, ridiculous.”

But the NGA didn’t stop there. Dipping into its campaign playbook, the NGA used the opportunity to educate the public on a fundamental policy issue affecting natural gas infrastructure in Massachusetts:

“Because of current financial incentives in the power market, most power generators in the region that run on natural gas do so without ‘firm,’ or guaranteed, pipeline capacity transportation arrangements,” the NGA statement explained. “The regional power grid operator, Independent System Operator (ISO) New England, recognizes this reality by paying owners of gas-fired power plants to switch to dirtier-burning fuel oil when the gas-delivery system is under maximum strain.

“Local gas utilities that serve residents and businesses, on the other hand, have signed up for and secured firm pipeline capacity to meet customer demand,” the NGA continued. “We can only imagine the outcry if they had failed to reserve enough gas supply, and homeowners, schools, hospitals, nursing homes, businesses and industry lost access to fuel.”

Signs of Strain

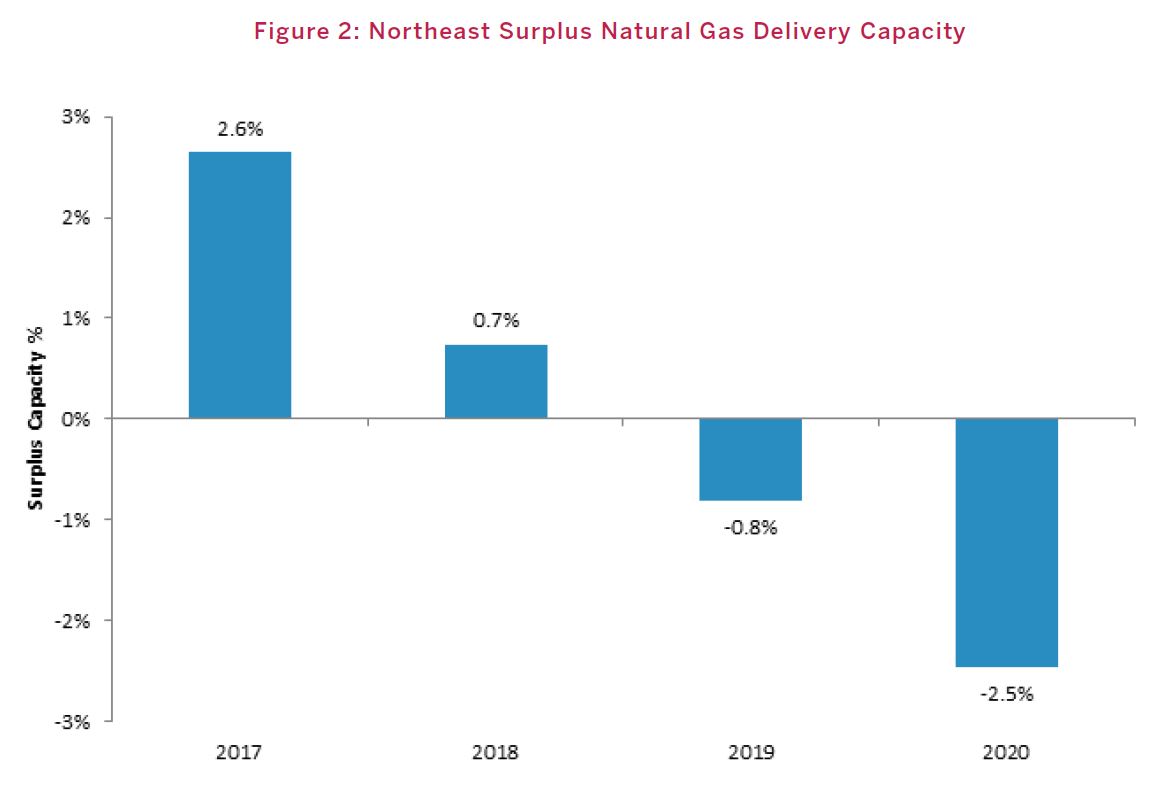

The dilemma for Massachusetts and New England is that, while electricity production accounts for nearly half the region’s natural gas demand, only a portion of it is under firm contract. So, on cold winter days, the available capacity goes to firm transportation holders, such as local gas utilities. As a result, electricity prices can spike dramatically.

Electricity producers contend that the short-term focus of the power market provides little incentive for long-term pipeline contracts. In response to high winter electric prices, several states allowed electric utilities to sign up for gas pipeline capacity. Their thinking was that since generators won’t commit to pipeline capacity, electric utilities under regulatory supervision might step in to solve the price-shock problem.

Recognizing that pipeline constraints were the cause of high winter electric rates, the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities proposed to let electric utilities pass through costs to electric ratepayers when it is in the public interest. But the state Supreme Judicial Court shot down that proposal last year on the grounds that it violated the 1997 electric utilities restructuring act.

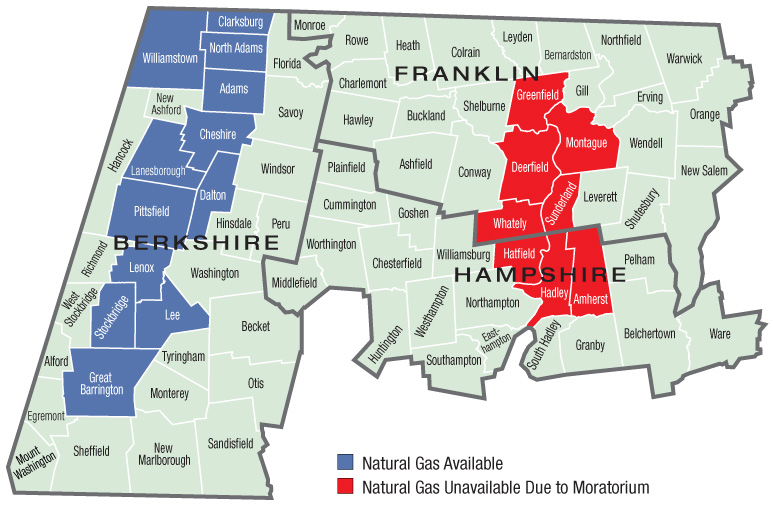

The problem isn’t limited to power generation. Berkshire Gas Company and Columbia Gas of Massachusetts imposed moratoriums on new residential and commercial gas service in 10 communities during 2014 and 2015 due to limited pipeline capacity. In a March 2015 letter to customers, Berkshire Gas pinned its hopes on the proposed Northeast Energy Direct pipeline.

“To be clear, inexpensive natural gas has never been more plentiful in the United States than it is today. It is the limited ability to deliver that natural gas to customers that presents today’s challenge,” Berkshire wrote. “While we are hopeful that a new pipeline project being proposed by Tennessee Gas can provide the additional pipeline capacity that is needed in the region, until such time as it is permitted and built, the moratorium will remain in place.”

But the Northeast Energy Direct project was canceled by Kinder Morgan in April 2016 due to insufficient contractual commitments (local gas utilities had signed up, but no power generators). The pipeline was to have added 1.3 Bcf/d of incremental capacity to Kinder Morgan’s existing Tennessee Gas system. Similarly, Enbridge withdrew its application with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) for the Access Northeast pipeline earlier this year, citing a lack of policies to support project financing in the region. Access Northeast, designed to meet power generation needs, would have upgraded 125 miles of the existing Algonquin pipeline system. It remains in the proposal stage.

The Marcellus Paradox

The transition to natural gas has been so successful that Massachusetts now risks electricity shortages during peak demand because so much of its power generation depends on gas. Oil now fuels less than 3% of the Commonwealth’s electricity production, and its last coal-fired plant – the 1,530-MW Brayton Point Power Station – was permanently shut down in May.

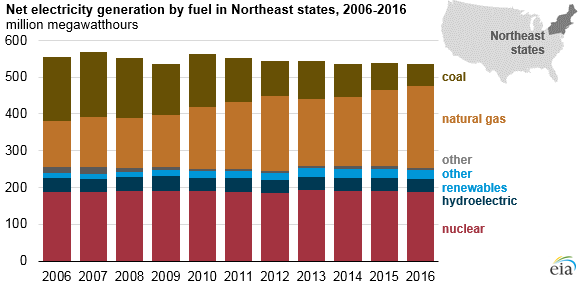

The head of New England’s power grid recently said reliable delivery of electricity during deep-winter cold snaps is already precarious and will become “unsustainable” after 2019, when Entergy will permanently close its 680-MW Pilgrim Nuclear Generating Station. Hydro and other renewable sources now provide about 15% of Massachusetts’ electricity.

The NGA is sounding an alarm with its awareness campaign, but it is also publicizing a solution: While Massachusetts was growing more dependent on natural gas, a technology revolution was turning the nearby Marcellus Shale into a massive source of natural gas to meet growing demand and reduce electricity costs in the nation’s priciest power market.

The problem is getting it there.

“If the Marcellus gas doesn’t flow into the Northeast, it’s going to flow somewhere else,” warned Paul Moran, associate director of the Energy practice at Navigant Consulting. “The Northeast region could be walking away from a valuable resource.”

Moran said there are unique constraints in Massachusetts and the Northeast region that make pipeline capacity expansion more difficult and necessary, including older pipe that makes it more challenging to add compression.

“The economics of power generation make it difficult to add capacity in any region, but inconsistent and sometimes hostile policies create a greater challenge here – and capacity issues have a more pronounced effect in the Northeast than in markets where an abundance of pipelines reduces the impact,” Moran said.

Adding to difficulty, organized opposition to pipelines has grown increasingly aggressive.

“Environmentalists have hijacked the story,” Moran said, addressing the primary motivation for the NGA’s awareness campaign. “For most people, this is not top of mind, but there is a very vocal minority that just does not want any type of hydrocarbons.”

The Chamber Chimes In

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce joined the effort to gain public support for natural gas with a 2017 report by its Institute for 21st Century Energy, which answers the question, “What if Pipelines Aren’t Built into the Northeast?”

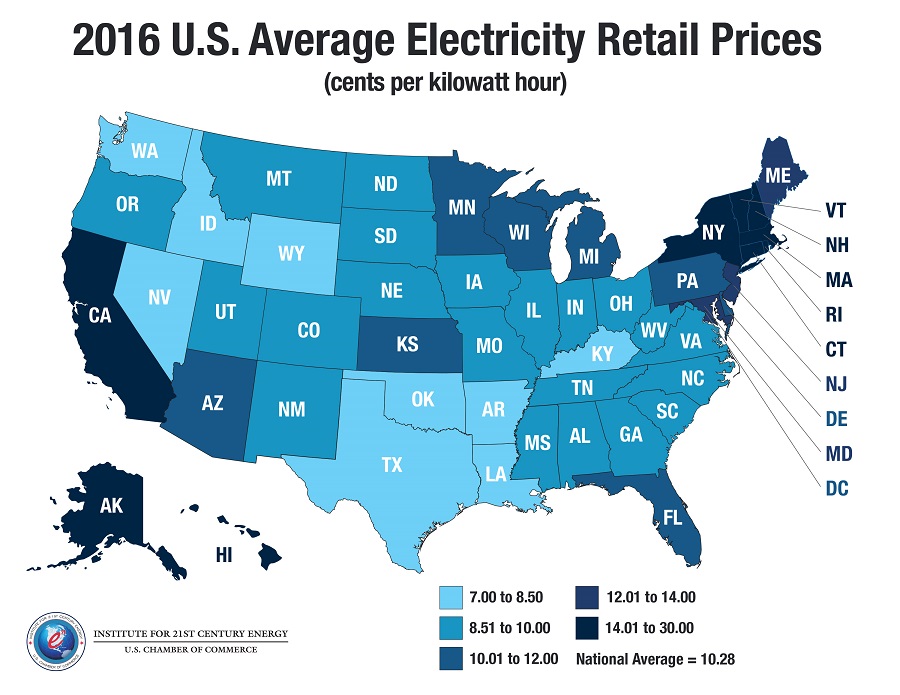

The Chamber reported that a lack of pipeline infrastructure in the Northeast has resulted in some of the highest electricity rates in the nation, and the lack of additional pipeline infrastructure will cost more than 78,000 jobs and $7.6 billion in GDP by 2020 in the states it examined. Massachusetts accounted for 8.700 of those jobs and $792 million of the lost GDP, according to the report.

“Environmental groups seeking to ‘keep it in the ground’ are fighting to block virtually every project that would bring additional natural gas into the Northeast, “ said Karen Harbert, president and CEO of the Energy Institute. “As a result, residents in the Northeast are paying the highest electricity rates in the continental United States, with no relief in sight if infrastructure is not built.”

Residents in the Northeast region pay 29% more for their natural gas than the U.S. average and 44% more for their electricity, according to the report. Six of the 10 states where residents pay the highest prices for electricity in the country are New England states, the report said, with Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts and New Hampshire all above 16 cents per kilowatt hour, compared with a national average of 10.42 cents.

“Currently, natural gas demand in New England averages 9 to 10 Bcf/d, with demand peaks in the winter reaching 20.8 Bcf/d. The existing natural gas delivery network is simply not robust enough to facilitate these spikes.”

Toward a Hybrid Grid

The NGA represents natural gas interests in nine states, and its board of directors includes executives from most of the transmission companies, LDCs and LNG importers that operate in the region. And what does the organization think about generating more of the region’s electricity with renewable energy sources?

“Our member companies are not opposed to renewables. In fact, we welcome them and believe they should be included in supply portfolios. But natural gas is a very critical part of the energy supply, and it seems to get dismissed and lumped in with coal and oil far too readily by some people who want to phase out all carbons,” NGA’s Kiley said.

“I think there’s a real misunderstanding up here that people think you can just flip a switch and all of a sudden we’re all renewables,” Kiley added. “And, by the way, there is also opposition to renewables. It might be a great idea from an energy perspective to site a wind farm on a mountain ridge or fill up some nice fields with solar panels, but overcoming opposition to get those projects approved is not easy to do.”

At the U.S. Department of Energy’s last Quadrennial Energy Review, Stephen Rourke, ISO New England’s vice president for system planning, said the electric grid will look very different in five to 10 years as Northeast states pursue their goals for reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Rourke explained that the region is transitioning to a “hybrid grid, with grid-connected and distributed resources, and a continued shift toward natural gas and renewable energy.”

If everybody shared this view of the future, there would be no need for NGA’s awareness campaign.

“I don’t think the zealots who protest these pipelines see natural gas as a bridge to renewable energy. I think they want to cut it off immediately,” Kiley said. “We need to do whatever we can to educate the public and make sure people understand that it’s just not going to happen that fast, nor can it.”

Comments