March 2018, Vol. 245, No. 3

Features

Operators Race to Build Pipelines as Permian Nears Takeaway Capacity

Permian Basin oil production will exceed takeaway capacity by mid-2018 and likely result in heavy discounting of Permian crude until enough pipeline capacity is added to handle the soaring volume, analysts predict.

Increasing constraints and projected output have triggered a race to build or expand pipelines to deliver Permian crude to Gulf Coast refineries and export terminals. At least 2.4 MMbpd of potential new Permian oil pipeline capacity has been proposed by a half-dozen operators, and those who have progressed to open season have reported strong customer interest.

“The extent to which this pipeline congestion materializes will depend on how much production increases, and anybody who makes those production forecasts is making guesses based on drilling rates and the expected productivity of new wells. But it’s a very strong signal that we’ve got this sudden batch of new pipelines coming to market,” said Sandy Fielden, director of Oil and Products Research for Morningstar Commodities Research.

“The only reason these midstream companies are doing that is because of an expectation that there’s going to be a significant increase in production,” Fielden said. “Exactly when that congestion occurs is obviously the big question, but our expectation is that demand will surpass capacity around the second quarter of this year.”

Tariffs Rise

As the hottest U.S. shale oil play, Permian Basin production has been pushing against takeaway capacity since last year, when average daily output grew to about 2.42 MMbpd from 2.02 MMbpd in 2016, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

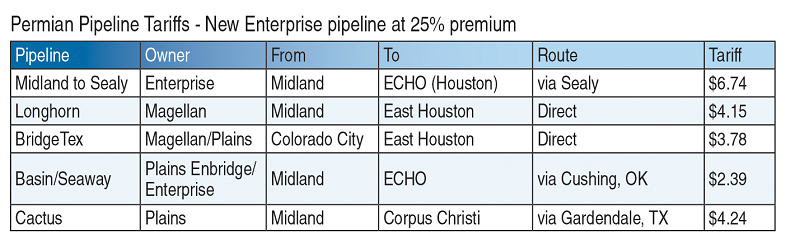

Between January and October 2017 alone, average output grew 19% to 2.6 MMbpd. Total Permian takeaway capacity rose to about 2.8 MMbpd in early December, shortly after Enterprise Products Partners’ new 300,000 bpd Midland-Sealy pipeline came into service. The timing allowed Enterprise to set a tariff of $6.74/bbl for uncommitted walk-up shippers – a $2.50/bbl than the next-highest competitor for a comparable Permian-Gulf Coast routes.

The effort to predict production growth and the capacity to handle it has been going on for months. One of the indicators of a potential shortfall in available takeaway capacity is a negative spread between the price of WTI at Midland and its price in Cushing, OK. EIA predicted last May that new pipeline infrastructure should accommodate the expected rise in Permian oil production, but that view is being challenged in the near-term.

“The Midland-to-Sealy pipeline added enough capacity to prevent an immediate crisis at the end of last year, but if production continues to increase as we expect, it won’t be enough to accommodate production in the second half of this year,” Fielden said. “The number of proposed pipeline projects is extraordinary, but they’re effectively competing for the same producers. They typically don’t all get built, but a big portion of those pipelines will get filled if production takes off as predicted.”

Permian oil production is projected to almost double again to 5.3 MMbpd from 2017 by the end of 2020, according to Morningstar.

Growing Consensus

Upstream and midstream companies alike are planning for significant growth in Permian crude production, pipeline construction and related infrastructure development. Some recent indications of demand include:

- Epic announced in December it received sufficient customer interest to sanction its proposed 590,000 bpd crude pipeline from the Permian Basin to Corpus Christi. The 730-mile pipeline, expected to begin operations in 2019, will be laid alongside an NGL pipeline now under construction.

- Sara Ortwein, president of ExxonMobil’s XTO Energy subsidiary, said in late January the company plans to triple its Permian Basin production by 2025 and invest more than $2 billion in terminal and transportation infrastructure expansion “to efficiently move ExxonMobil and third-party production” to Gulf Coast destinations.

- Enterprise said its new Midland-to-Sealy crude oil pipeline flowed an average 330,000 bpd after coming online in November and should reach 450,000 bpd when fully operational in April. Graham Bacon, executive vice president of Operations & Engineering, told investors in late January the company plans to further boost capacity with additional pumps and drag-reducing agents – potentially reaching up to 550,000 bpd.

- Plains All American Pipeline said it received enough interest in its 585,000 bpd Cactus II Pipeline open season to conduct a second binding open season. First flow is scheduled for the second half of 2019.

- Magellan Midstream Partners reported significant interest from potential shippers in its proposed 350,000 bpd pipeline. Magellan said it extended the open season to allow additional time to finalize binding commitments.

WTI Price Risk

If the predicted capacity squeeze comes true, history shows a price squeeze will soon follow. EIA noted in its May 2017 report that the Midland-versus-Cushing discount had recently widened to more than $1 per barrel but advised that the discount “is unlikely to be either as large or as persistent as it was following the rapid increase in Permian production from 2010 to 2014.”

At points in both late 2012 and mid-2014, WTI-Midland as priced at least $15 per barrel lower than WTI-Cushing, according to EIA. Morningstar said Permian producers were forced to discount WTI-Midland as much as $20 per barrel in the fall of 2014 before the 300,000 bpd BridgeTex Pipeline came online.

That was painful enough with oil prices above $100/bbl, but it could threaten producer breakevens at current prices. Delaware Basin breakeven prices fell to approximately $40/bbl by 2016, according to Rystad Energy, while 2018 WTI prices are forecast to be $60-per-barrel range.

“The level of discounting is primarily determined by the cost of alternative transport,’” Fielden explained. “If there’s no pipeline capacity, and I have to go to rail or truck to deliver my barrels to market, what does that cost? Generally speaking, it forces producers to price their crude low enough to offset that extra cost of transportation.”

The good news, Fielden said, is pipeline squeezes don’t last long in the shale era, because they encourage midstream companies to accelerate new projects or expand existing capacity to fill the gap. The trend has already started.

Magellan announced plans to boost BridgeTex capacity by 40,000 bpd in 2018. Enterprise also announced plans in December to convert an existing NGL pipeline to transport Permian crude to the Gulf Coast the first half of 2020, after its new Shin Oak NGL Pipeline begins service near the second quarter of 2019. The conversion would provide an additional 650,000 bpd of capacity to Enterprise’s crude oil hub in the Houston area.

Most refineries on the Gulf Coast are configured to process heavier crudes and have plenty of light crude supply, so an inability to transport added production should not affect them much. Most of the new oil production in the Permian is bound for export markets, Fielden said.

Comments