November 2018

Features

Gas Remains Key to UK Energy

By Nicholas Newman, Contributing Editor

Even today, gas from the North and Irish Sea supplies almost half of the United Kingdom’s needs leaving the lion’s share to imports via four pipelines from Europe and Norway and LNG tankers.

With 80% of the U.K.’s 25 million homes powered by gas, one quarter of the country’s electricity is generation by gas-fired power stations, and a fifth is consumed by industry.

Gas is a key element of the U.K.’s energy mix. In 2017, the U.K. consumed 74.3 Bcm, and its gas storage capacity of 4 Bcm was just enough to deliver over a quarter of natural gas demand on a cold winter’s day. The closure of Centrica’s Rough long-term storage facility last year reduced gas storage capacity to just 1.3 Bcm, equivalent to 1.6% of the U.K.’s annual gas demand. The U.K. has only 14 days of gas storage capacity, compared to 87 in France, 69 in Germany and 59 in Italy.

Natural gas consumption in the U.K. fell significantly from 92.7 million metric tons of oil equivalent to 36 million metric tons between 2003 to 2017. According to EIA statistics, gas provided 38% of primary energy needs in 2016. Heating accounts for the bulk of gas demand, and this varies from day to day in line with the climate, season and growing contribution of renewable power. In the absence of large-scale energy storage, the intermittency of renewable energy should increase the importance of gas fueled peaking power plants.

UK Supplies

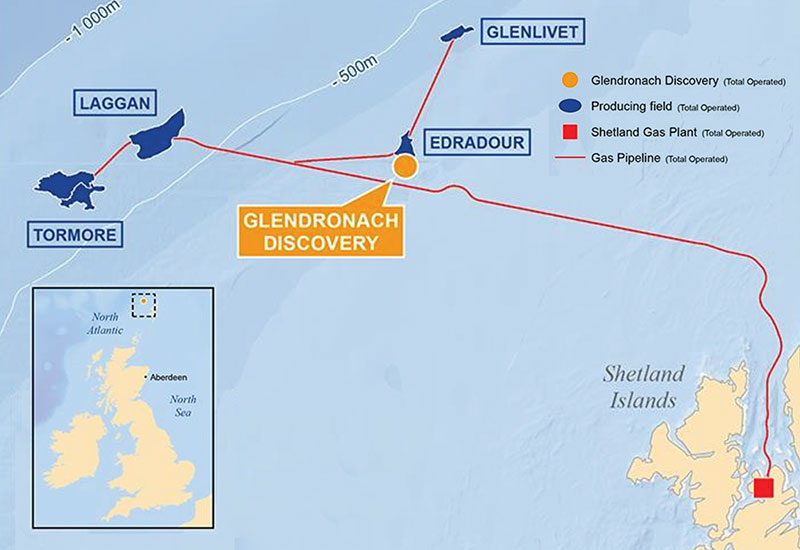

British Gas, the U.K.’s major utility, estimates offshore fields in the North Sea and East Irish Sea supplied 45% of gas consumption in 2017. However, these domestic sources are in seminal decline, and it is thought unlikely that Total’s discovery of the 1 Tcf of gas Glendronach field, west of Shetland in September, will arrest the downward trend of U.K. gas production (Figure 1).

The subsea interconnector pipelines crossing the North Sea have a capacity of 60 MMcf/d. Norway supplied 61% of the U.K.’s pipeline imports and Holland 7%, with the remainder coming from Algeria, Russia and central Asia.

LNG tankers brought in 9% of the U.K.’s gas demand with Qatar supplying 29%, and Algeria and Trinidad providing 1% each. The remainder came from the United States, Egypt and Nigeria, according to the U.K.’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

The U.K.’s three operating commercial LNG terminals can handle about 35 mtpa of LNG. Two are located at the southwestern Wales port of Milford Haven and the third is east of London on the Isle of Grain. Swiss commodity trader Trafigura, will open a $39.2 million (£30 million) LNG terminal in Newcastle next year to accept imports from the U.S. and Russia.

“Given the growth in volumes globally and the flexibility of U.S. supplies it is likely that LNG shipped from the U.S. will make up the lion’s share,” said Hadi Hallouche, Head of LNG trading at Trafigura.

Storage Facilities

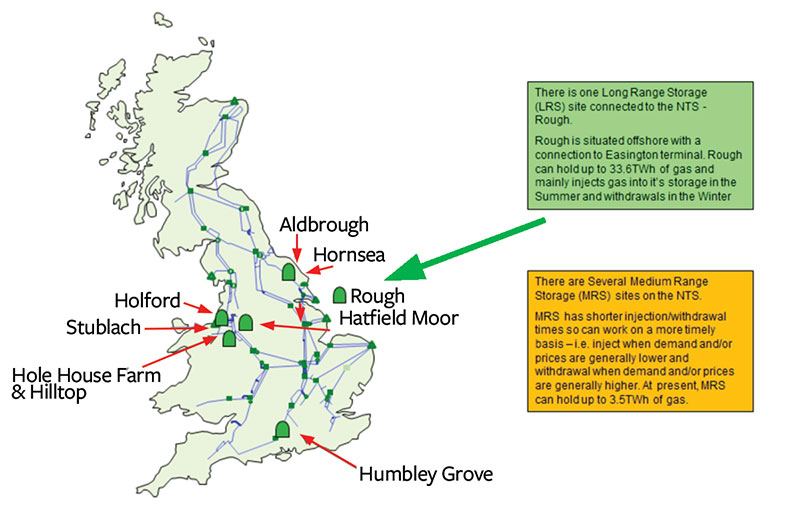

With a high dependency on gas, an operational reserve to balance supplies and ensure energy security is considered crucial. The U.K.’s gas storage facilities are found in depleted oil and gas fields and salt caverns.

Following the closure of the Rough storage facility, there are just six gas storage sites for market interests to draw upon. These are located at Aldbrough and Hornsea in East Yorkshire, Hatfield Moors in Yorkshire, Humbly Grove in the Weald, Holford and Hole House Farm in Cheshire (Figure 2).

Of these, the Aldbrough facility provides 7%, or 370 million m³/d, of the U.K.’s total gas storage capacity and can deliver gas to the National Transmission System at the rate of 40 million m³/d – equal to the daily consumption of 8 million homes. There are currently 20 tentative proposals to develop new gas storage facilities.

The Rough storage facility, before its closure in April 2017, accounted for 70% of the U.K.’s gas storage capacity. It is an open question whether there is a need to compensate for this loss of capacity.

The case for additional gas storage in the U.K. depends on future energy prospects and the availability of alternative solutions. Gas storage is essential to maintain supplies by providing a reserve during spikes in demand or disruption to supplies. The sudden closure of the Forties pipeline, which carries one-third of Britain’s offshore gas in late December 2017, caused a spike in gas prices from 72 cents (55 pence) a therm at the start of December to 84 cents (64.3 pence) on New Year’s Day. It could have been much more.

Also, at times of extreme weather in Europe, the U.K. finds it difficult to compete for extra gas supplies. Gas storage could also prove invaluable for energy security, particularly when the U.K. has a heavy dependence on imports of LNG from Qatar, a country that is potentially vulnerable to economic and political sanctions from its neighbors.

In addition, the U.K. demand for gas by power generators increased 4.4% in 2017 reports, according to an Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. This upturn is likely to be sustained due to the closure of coal plants, delays in the nuclear building program, growing electrification of transport and fluctuations in renewable energy.

Not to be overlooked, there is Brexit. Andrew Morris, Pori Management Consultants asks whether following Brexit, “We will enjoy the same gas market benefits as before.”

The role of gas storage depends on the U.K.’s future market and environmental needs. Some argue diversity of supply is the key to energy security. For example, a representative for National Grid was reported by Reuters as saying, “Britain gets its gas from its North Sea reserves, from Norway, via pipelines linked to continental Europe, from shipments of liquefied natural gas, or from storage. It is this mix that enables security of supply.”

Moreover, the cocktail of demand management policies, investment in energy efficiency and energy storage is likely to reduce the need for gas storage. For example, the National Grid holds contracts with major industrial consumers, to reduce consumption or even switch off, when market supplies are especially tight to protect domestic customer needs. In the longer term, gas demand could be cut by electrification of heating, the use of greener gases such as hydrogen, district heating schemes or some combination of all three.

Already, parts of the U.K. gas market including, the cities of Liverpool and Manchester, are part of Cadent’s ambitious $783.3 million (£600 million) testbed project blending hydrogen with methane, as part of government ambitions to cut the carbon footprint of the gas that heats most of Britain’s homes.

Cadent believes mixing in hydrogen for up to about one-fifth of gas supplies could be done without harming domestic boilers and cooking equipment. However, to fully switch to hydrogen, the 26 million gas boilers in the U.K. would need to be swapped for hydrogen-compatible models.

In sum, while gas storage capacity is woefully low compared to its European neighbors, the case for additional gas storage facilities in the U.K. is weak, according to energy expert Morris, who believes “current regulatory and market conditions mean that there is not a bankable business case for new gas storage.” P&GJ

Comments