January 2019, Vol. 246, No. 1

Features

Shell Falcon Pipeline Gets Important FERC Approval

By Tom Ewing, Business and Environmental Reporter

At least a small measure of celebration likely buzzed through the offices at Shell Pipeline Company (SPLC) on Sept. 7. The reason: a mid-day announcement from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) that the company’s petition for a declaratory order pertaining to a new interstate pipeline had been granted.

The project at issue is Shell’s $90-100 million Falcon Ethane Pipeline System, a 98-mile long pipeline to transport ethane within and between Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio. It’s been a long time in the planning stage and – just as critically – fundamental to the success the company’s $6 billion ethane cracker plant under construction in Monaca, Pa., about 30 miles north of Pittsburgh, on the banks of the Ohio River.

According to IHS Markit, an economic consultant working on behalf of Pennsylvania, the cracker is the largest private investment project in the history of the Commonwealth. Operating employment is estimated to reach 600 full-time jobs.

If FERC had dismissed the petition, there would have been no reason to proceed with the construct of the pipeline since the company would not have been allowed to enact the revenue and business practices necessary to make it work financially.

The Monaca plant will be the first regional cracker plant in the northeast, within what Shell calls “the heart of the market” for polyethylene production. The Monaca location, according to Shell, presents access to “more than 70% of the North American polyethylene market,” and the pipeline will “allow enhanced access to growing domestic Appalachian production in the Marcellus and Utica shale reservoirs.”

Shell Pipeline Company LP will own the Falcon Ethane Pipeline, and Shell Chemical will own and operate the cracker plant. Planning for the cracker started in 2012; Falcon planning began in 2015. Capacity is about 70,000 bpd.

Eastern Ohio and western Pennsylvania have a long history of energy production. To a large extent, though, surely in the past half-century, this regional energy wealth has been exported. Now, the Falcon pipeline and cracker plant present new opportunities to recover raw material wealth and the chance to exploit that wealth at home, to use it locally for production and then export higher value products and materials, from food packaging to housewares to automotive and medical devices.

IHS Markit references a “roadmap for the petrochemical and plastics value chains in Pennsylvania.” This kind of optimistic, robust economic development doesn’t just happen – it takes a lot of coordinated work and planning among public and private sector leadership. FERC’s decision is critical within this big-picture vision.

In its petition to FERC, Shell references these future regional energy-economic opportunities. The Falcon pipeline, Shell writes, in addition to serving the new cracker at Monaca, would be situated to “provide additional transportation options for interstate shippers of ethane in the growing market created by continued Utica and Marcellus natural gas production and the associated creation of ethane supplies at natural gas processing plants located in the areas to be served by the Falcon Pipeline.”

IHS forecasts $7.3-10 billion will be invested in NGL assets (gas processing facilities, NGL fractionators, NGL pipelines and NGL storage facilities) in three states (Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia) between 2017 and 2025. That sum does not include the new Monaca cracker.

IHS forecasts between 2026 and 2030 ethane from the Marcellus and Utica Shale plays will be enough to support up to four additional world-scale ethane steam crackers in the region, after meeting the demand from Shell’s Monaca cracker. (Planning is underway for a second cracker in Belmont County, Ohio, south of Harrison County, which contains one of the Falcon starting points in Ohio.)

Even more impressively, this projected supply exceeds current demand from pipelines currently shipping ethane out of the region, as well as future exports. The Falcon project – and getting it done – presents economic benefits well beyond one company’s success. It portends an economic boom and a sustainable one, not boom-and-bust.

Liquids pipelines, such as those for ethane, advance to construction largely through state permitting processes, as well federal agencies, such as the Army Corp of Engineers, for example, if rivers and streams are involved. With liquid pipelines, at least compared to (interstate) natural gas pipelines, FERC’s authority differs and is more limited; it does not extend to rights-of-way and siting issues.

FERC’s liquids pipeline authority includes providing “advance holdings” via the issuance of a declaratory order regarding the lawfulness of rates and terms of service for projects like Falcon. Shell’s filing notes FERC has “repeatedly recognized the need for pipelines to obtain up-front regulatory approvals before undertaking major capital expenditures;” a process “in the public interest,” according to FERC guidance documents.

For projects like Falcon, then, FERC’s move is primary, avoiding a stalemate. FERC’s decision provides the upfront certainty a project needs, regarding rates and terms of service. SPLC writes that without this certainty “shippers will not be able to justify taking up the balance sheet and commercial burdens associated with the ship or pay commitment required by the TSA (transportation service agreement); in turn, SPLC would not be able to justify the cost of the project.”

Shell filed its petition for declaratory order on July 3 (and, of course, the required $27,130 filing fee). It wrote “in anticipation and furtherance of the project commencing service in early 2020, SPLC respectfully requests that the Commission act on this Petition by no later than Sept. 7, 2018.” Once a company files its petition it then just waits; there is no follow up between company and FERC, say, for additional information or clarifying text or comments.

Importantly, FERC’s move was timely, keeping Falcon aligned with separate, multiple parts in complex state and federal regulatory processes. Shell wants to start pipeline construction soon, extending through 2019, with service starting in early 2020. That schedule would have faltered if FERC’s decision had been delayed; a decision in February, for example, would be more of a monkey-wrench than a lever.

True, FERC barely met Shell’s requested deadline. However, there are no statutory requirements for FERC to respond to petitions for a declaratory order by a certain date. On some issues, there’s no requirements for FERC to respond at all. However, the commission “makes an effort to respond by the deadline dates requested,” said a FERC spokesman in an email. This effort is important considering the current expansive dynamics characterizing energy expansion in the United States.

FERC staff has noticed an increase in petitions filed by interstate oil pipelines seeking commission approval of rate structures for new or expansion pipeline projects. Interestingly, though, the commission does not maintain statistics or track filings, so it cannot compare year-to-year activity.

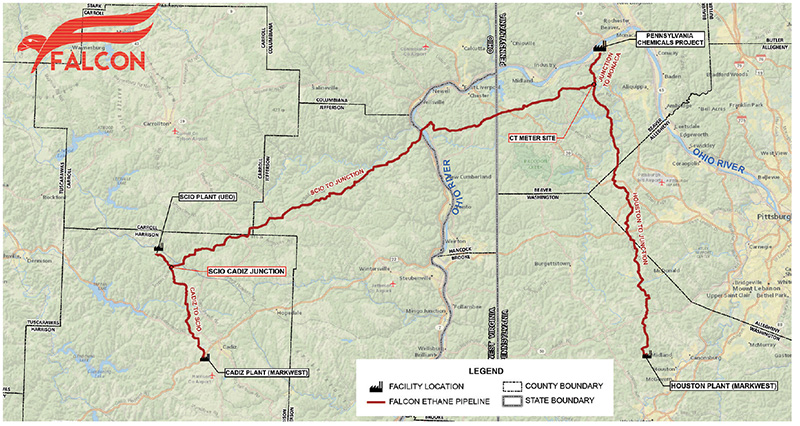

The Falcon Pipeline will traverse three states (see map). Ethane will originate at three locations – two in Ohio, in Harrison County, about 120 miles east of Columbus, and one in Houston, Penn., in Washington County. The east-west Falcon portion will traverse about 43.6 miles in Ohio, 8.5 miles in WV and 45.5 miles in PA. The intrastate north-south route from Houston to Monaca is about 35 miles.

The pipeline starting points are at natural gas processing and fractionation facilities, at Cadiz and Scio, in Ohio and at Houston. After separation, the liquid ethane will be transported via 12-inch pipelines to a junction meter site in Raccoon Township, Beaver County, Penn. From there, the pipeline increases to 16 inches, terminating at the cracker plant in Monaca. The routing includes an Ohio River intersection a few miles south of East Liverpool, Ohio. Details are not yet available on this river crossing. State permitting remains very much at play.

The shortest portion of the pipeline route is in W. Va. and its permit was approved by the state in February, although a section of that permit was reopened for review in late August because Shell is seeking some modifications.

In Ohio, a state EPA spokesperson said the “Falcon/Shell water quality application is still under review by Ohio EPA.” He suggested checking back “in a couple weeks for a status update.”

In addition to federal water and wetland issues, wildlife and endangered species analyses range from bald eagles to Indiana Bat habitats.

On June 1, Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) sent “technical deficiency letters” to Shell Pipeline regarding Chapter 105 applications – “Water Obstruction and Encroachment Permits,” required for activities “located in, along, across or projecting into a watercourse, floodway or body of water, including wetlands.” On Aug. 1, Shell responded to DEP’s technical deficiency letters, preparing a separate response for each county – Allegheny, Beaver and Washington counties.

In its July petition, Shell sought FERC approval on 10 business-related proposals, including the appropriateness of Shell’s open season efforts, committed rate structures and approval of anchor shipper terms and extension rights.

In its order, FERC wrote “based on the representations in the petition, the commission will grant all the rulings requested by Shell as consistent with commission precedent and policy.” It commented Shell held a “well-publicized open season during which the preferential capacity rights it seeks approval for were made available to any interested shipper that was willing and able to meet the pipeline’s contractual requirements.”

FERC also noted the petition was unopposed, at least at the federal level. FERC’s process allows interested parties to comment or, more substantively, to formally intervene in these cases.

At the state level, the public hearing process is different, and there is consistent opposition at each stage of Falcon development, particularly in Pennsylvania. One local concern is possible risk to the 405-acre Ambridge Reservoir in Beaver County, a source of drinking water.

In a “Proposed Project Antidegradation Analysis” Shell writes that “the pipeline will be operated and maintained in accordance with government regulations so that integrity of the pipeline remains intact.”

Oversight will include “frequent use” of smart pigs. Meter and valve sites will be tested every six months and monitored remotely. Critical station valves will be tested every six months. Leak detection will be monitored remotely 24 hours per day.

FERC’s ruling concludes that the petition is “consistent with precedent,” and accordingly, “based on the facts and representations made by Shell, confirms and approves the rulings as requested in the petition.”

Shell’s original petition provides insight into the depth of the Marcellus-Utica natural gas market. The petition notes, for example, that after its one-month (Oct. 17, 2016 to Nov. 18, 2016) open season effort “SPLC received sufficient shipper commitments to support the project.”

In other words, they got the business. Shell said Falcon will provide needed new capacity “to serve the growing polyethylene market,” in addition, of course, to the Monaca plant.

For Shell and Falcon, there’s a lot more work ahead but FERC’s move keeps this critical project on track. P&GJ

Comments