July 2020, Vol. 247, No. 7

Features

FERC Approval Gives Alaska LNG 10 Years to Start Operations

By Larry Persily, Alaska LNG Project Updates

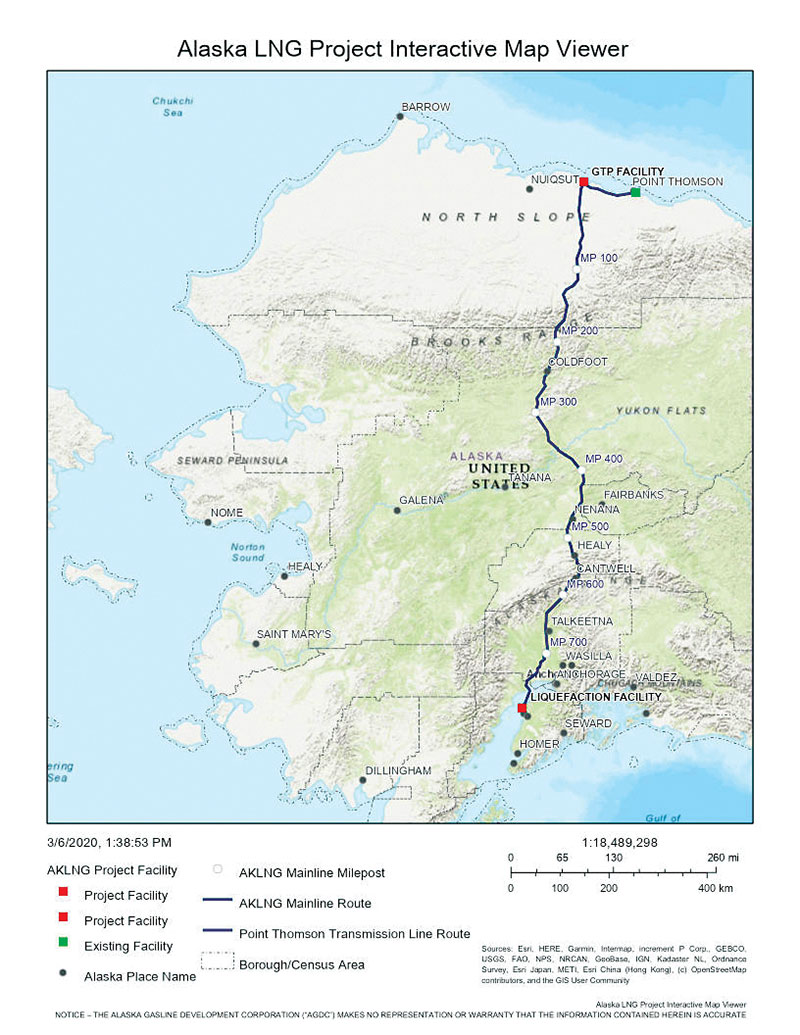

Eederal authorization for the Alaska liquefied natural gas (LNG) project sets a 10-year deadline to start operating the gas pipeline and liquefaction plant, twice as much time as regulators have generally allowed for other U.S. LNG export terminal developers to build multibillion-dollar facilities.

But none of the other ventures approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) include the Alaska project’s 870 miles (1,400 km) of pipeline – adding to the engineering and construction time – nor do they face the seasonal limitations of building in Alaska.

FERC approved the state-led project application May 21.

The U.S. LNG development with the next-longest accompanying pipeline, the $10 billion Jordan Cove Energy Project, proposed for Coos Bay, Ore., was given five years to start moving gas when FERC approved the project in March. Jordan Cove, proposed by Calgary-based Pembina Pipeline, includes a 229-mile (369-km) pipeline across the southern part of Oregon to deliver feed gas from the Western Rockies and Canada to the coastal LNG plant.

Regardless of FERC’s requirement to start operations by 2026, opposition from the state of Oregon and tribal, environmental, fisheries and landowner groups – along with a shortage of LNG customers, investors and financing – is likely to push any start-up date past the five-year timeline, if the development even goes ahead.

Opponents of the LNG project in Coos Bay, Ore., had sought a rehearing at FERC, which the commission denied the same day it authorized the Alaska project. Within a week, opponents had filed two lawsuits in federal court against FERC’s actions.

No Extensions

Developers can, and often do, request extensions of the FERC deadline to start operations.

For example, the commission in 2016 authorized construction of Golden Pass LNG in Texas, a venture of ExxonMobil (30%) and Qatar Petroleum (70%), with export operations to start by 2021. The developer in 2019 asked for an extension to 2026, which FERC approved.

In Alaska, FERC in 1995 authorized the Yukon Pacific project to pipe North Slope gas 800 miles (1,287 km) to an LNG plant proposed for Valdez. The economics of the $18.4 billion project (1996 estimate) did not work out and the developer requested, and was granted, four extensions of three years each from FERC, with the last one expiring in 2010. Regulators in 2010 denied the company’s request for a fifth extension and in 2011 the developer relinquished its federal rights-of-way.

In denying the request for another extension, FERC in 2010 said the Yukon Pacific project’s environmental impact statement (EIS) is “outdated and can no longer be used to support the authorization.” In addition, an agency official wrote, “There have also been numerous changes in regulatory requirements since 1995, from both an environmental and safety perspective, that must now be addressed.”

A quarter-century after Yukon Pacific won FERC approval, the Alaska LNG project faces similar economic problems in a challenging global market for fuel.

The state-funded applicant, the legislatively created Alaska Gasline Development Corp. (ADGC), adopted a strategic plan in April to turn over the project lead – and spending – to private parties if the corporation can find anyone interested in taking on the development. The state has been paying almost all the bills for more than three years.

Any change in project ownership would have to go through FERC, though it is unlikely that a transfer or addition of partners would encounter a regulatory burden.

The AGDC board of directors expects to review at its June meeting an update to the project’s three-year-old construction estimate of $43 billion. Under the board’s strategic plan, the corporation will sell off the project’s assets if no one steps up to take over as lead.

Federal Concern?

FERC’s review of an LNG project application considers the environmental impact and safety of the facilities, not the economics. The U.S. Department of Energy makes the decision whether the export of the gas is in the public interest. It, too, does not look at a project’s economic viability.

In 2015, the Department of Energy granted export authority to the Alaska LNG Project LLC, a venture of North Slope oil and gas producers ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips and BP. The state is not a party to that company or the export authorization.

The Alaska LNG project started at FERC in September 2014 when the sponsors, which then included the three major North Slope producers along with the state, initiated the pre-filing process. After the producers left the development team in 2016, citing weak project economics, the state proceeded on its own and submitted the lengthy application to FERC in April 2017.

FERC issued the draft environmental impact statement in June 2019, and the final EIS in March 2020.

The 127-page May 21 commission authorization requires AGDC to provide additional information and – in standard approval language – obtain all authorizations required under federal law before construction may begin.

Among the dozens of conditions in the FERC order are some specific to Alaska and many others that are routine:

- Before any site preparation, AGDC shall file an overall project schedule and procedures for controlling access to work areas during construction.

- Before any site preparation, the developer shall file a cost-sharing plan “for funding all specific security/emergency management costs that would be imposed on state and local agencies.”

- A team of environmental inspectors must be on-site during construction – the number to be determined by FERC – to monitor compliance and establish an environmental complaint resolution process.

- Before starting construction, AGDC shall file a revised feasibility study for crossing the Deshka River, about 100 pipeline miles (161 km) north of the LNG plant in Nikiski. The project team proposes to install the pipe by “micro-tunneling” for about 1,300 feet (396 meters) beneath the river and its banks. FERC wants to see updated, site-specific geotechnical information from additional soil borings. If the study indicates a change is needed in the crossing site or crossing method, FERC approval will be required. The Deshka is one of five rivers in which AGDC proposes micro-tunneling to route the pipeline beneath the waterway. During the EIS review, FERC asked frequent questions of the tunneling process and environmental safeguards.

- After construction of the Prudhoe Bay gas treatment plant and Point Thomson gas pipeline are complete, AGDC shall conduct seasonal monitoring for three years “to track caribou herd movement and determine if project infrastructure is creating a barrier to caribou movement,” and, if it is, propose to FERC steps to solve the problem.

- AGDC shall not begin any construction or establish temporary work areas until it “completes outstanding archaeological and architectural surveys,” and files plans “to avoid, reduce and/or mitigate effects on historic properties,” allowing time for state and federal historic preservation agencies to comment.

Should any intervenors in the Alaska LNG docket at FERC object to the authorization or its conditions, they may request a rehearing of the commission’s decision. Intervenors include the Center for Biological Diversity, Northern Alaska Environmental Center, Sierra Club, National Parks Conservation Association, Chickaloon Native Village Traditional Council, the city of Valdez, Matanuska-Susitna Borough and Kenai Peninsula Borough.

After the rehearing is denied or completed, an intervenor can go to court to challenge FERC, as opponents are doing with the Oregon LNG project.

Greenhouse Emissions

One of the major complaints by national opponents of the Alaska project – same as with almost all U.S. LNG export terminals – is the lack of consideration for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from consumption of the fuel at the receiving end. The commission rejected that challenge for the Alaska LNG project. “The end-use of the LNG is unknown and … the commission does not have the authority over and need not address the effects of the anticipated export of the gas,” the FERC order said.

“The commission once again refuses to consider the consequences its actions have for climate change,” Commissioner Richard Glick, a frequent critic of LNG project approvals, wrote in a dissenting opinion.

“The commission steadfastly refuses to assess whether the impact of the project’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions on climate change is significant. … That refusal to assess the significance of the project’s contribution to the harm caused by climate change is what allows the commission to perfunctorily conclude that the environmental impacts associated with the project are ‘acceptable,’” Glick wrote.

In a concurring opinion with the majority approval of Alaska LNG, Commissioner Bernard McNamee took exception with Glick’s statements. “The commission has no reasoned basis to determine whether GHG emissions will have a significant effect on climate change nor the authority to establish its own basis for making such a determination,” he wrote.

“Further, the commission is not positioned to unilaterally establish a standard for determining whether GHG emissions will significantly affect the environment when there is neither federal guidance nor an accepted scientific consensus on these matters,” McNamee wrote.

Glick’s objections also focused on the project’s potential harm to wildlife. “The commission concludes that the project will result in several significant, and often permanent, adverse impacts on the environment,” he wrote. “The project is expected to adversely affect six endangered species including polar bears, seals and whales. In addition, even with mitigation measures, the project is expected to have a significant adverse impact on the Central Artic Herd of caribou, permafrost, forest and air quality in areas such as Denali National Park.”

Long List

In his opening remarks at the start of the FERC meeting where the Alaska LNG project was authorized, Chair Neil Chatterjee made no mention of the debate over greenhouse gases. He said he was “pleased” that the commission was approving the project to commercialize North Slope gas for export and use in Alaska. “This is the 13th LNG project we’ve approved since I joined the commission,” Chatterjee said. He has served as a commissioner since 2017.

Just one of those 13 projects is under construction. The U.S. has six LNG export terminals in operation, with construction underway at two more, along with more than a dozen others at various stages of proposed or permitted development for the Gulf Coast.

The LNG market already was oversupplied last year due to weakened Asian demand growth, even before global shutdowns to reduce the spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic cut deep into economic activity and fuel demand worldwide. Since then, spot-market prices have crashed to record lows and several market-demand forecasts have changed significantly downward.

“We don’t see any additional North American export capacity getting sanctioned in the next decade,” Ross Wyeno, an LNG analyst at S&P Global Platts, said in a May 26 news report.

Author: Larry Persily publishes the newsletter Alaska LNG Project Updates. He was the federal coordinator for the Alaska Natural Gas Transportation Projects, 2010-2015.

Comments