November 2024, Vol. 251, No. 11

Features

Practical Approach to Managing Project Challenges

By Mustafa Abusalah, Learning and Innovation Manager

Creating an innovation platform requires an environment that encourages rapid adoption of industrial changes and an innovative mindset that never mistakes activity for progress.

Identification of learning gaps is essential: what the organization knows, what it needs to know and what it can learn are all vital if the organization is to be prepared for new challenges.

Questions an organization should ask include:

• What is our ability to learn, use our knowledge and innovate?

• What is the effectiveness and added value of creating an innovative platform?

Planning an innovation platform starts with a strategy that addresses the culture change requirements and a high-level plan to allocate resources and leadership. Most construction innovation activities are carried out at project level and need cooperation among different parties (Xue, et al., 2017).

Enterprise construction companies that have projects in different countries must connect innovation to projects and market the innovation ideas to get real buy-ins and get project teams on board.

This article will suggest a strategy and a practical approach that succeeded in creating a learning and innovation platform across an enterprise construction organization.

Case Description

The innovation platform discussed in this study was developed to manage innovation at Consolidated Contractors Company (CCC), a large multinational contracting organization, which has around 150,000 employees distributed all over the world. The organization is headquartered in Athens, Greece, and has offices in the five different continents.

Teams of senior and junior employees — including project managers, mechanical engineers, technicians, etc. — perform a variety of civil and mechanical construction projects such as building harbors, airports, tunnels and gas and oil plants in different contexts.

These teams might work onshore or offshore and sometimes in remote areas. The size of these teams may vary, depending on the size of projects, ranging from 2000 employees in smaller projects up to 30,000 employees in larger projects.

Due to this distributed nature of the organization and the dispersion of project teams, top management started to think about how to leverage and manage the dynamic knowledge and experience of such a vast number of employees to create a culture that supports innovation and knowledge sharing.

It is worth mentioning that the company increased its employees from 35,000 in 2003 to 160,000 in 2008. The current number of employees in January 2018 is about 150,000. This explosion in the number of employees further stimulated top management to think about flexible ways for capturing and managing knowledge and experience across CCC projects.

Until 2007, CCC mainly used a document management system for storing and organizing its knowledge into structured documents and reports. This system was ineffective in facilitating dynamic collaboration and sharing of knowledge and experiences. Consequently, top management decided to support the establishment of a Knowledge Management (KM) department to develop and manage a shared platform for collaboration and knowledge sharing within CCC.

The KM department was therefore officially established in July 2007. The KM department, after eight months of planning, launched a collaboration platform based on a corporate wiki, called “Fanous,” which is an Arabic word meaning “The Lantern” in March 2008 (Mansour, Abusalah, & Askenäs, 2011).

In order to put the wiki into operation, the KM department established a core team of senior employees and top managers. This team represented experienced organizational members who had been working at CCC for a long time. The team aimed at providing a basis for building and cultivating different specialized communities, as well as promoting the use of the wiki as a collaboration tool amongst their employees.

The Knowledge Management was based on five professional communities of practice (CoPs). Each community is specialized within a particular Domain and led by a community leader, manager and a number of community captains. There are also subject matter experts (SMEs) who are expert employees within the domain of the community, who give support if required.

CoPs are an agile approach used in CCC to gather cross functional teams from different projects to develop new pipeline construction methods or enhance existing methods in construction and the oil and gas field, which are the core business of the company. Those CoPs expanded to 12 and then some of them were transformed or retired, depending on business needs and requirements. Wiki was the base used for collaboration and communications among the CoP members and the company employees.

All CoP members are selected based on their seniority and level of experience, with full accessibility to add, edit, comment and change contributions on the wiki. Other people at the company could access the wiki but with roles limited to reading and commenting on the articles. In due course, as employees became more mature in using the wiki, the membership and authoring rights were extended to any CCC employee who joined the collaboration platform.

Each community has its own space on the wiki that includes community pages where community members collaborate and share knowledge with each other. Members can also contribute to other relevant communities on the wiki. In addition, all CoP members receive weekly newsletters, and they also can subscribe to certain topics in order to receive email notifications to keep them updated on any new contributions.

The wiki collaboration platform was extended in 2015 to include Questions and Answers, to help project staff ask questions of experts across the organization. Later, in 2017, a new Lessons Learned Platform was developed to enable project staff to exchange Lessons Learned with other projects to improve the corporate learning and innovation cycle.

Planning

Planning an Innovation Platform starts with defining innovation within an organization and creating a road map. A useful example definition is:

“Innovation is the actual use of a nontrivial change and improvement in a process, product, or system that is novel to the institution developing the change” (Sexton & Barrett, Appropriate innovation in small construction firms, 2003).

The role of technology transfer in innovation within small construction firms

The role of technology transfer in innovation within small construction firms, (Sexton & Barrett, 2004), in a definition developed with practitioners, emphasized that the outcome of innovation should enhance overall organizational performance. Based on their work together with (Dickinson, Cooper, McDermott, & Eaton, 2005) and (Freeman, 1989), in this paper we define the Innovation for CCC as:

“The successful exploitation of new ideas and leveraging technologies or business models to add value to the company’s operations.”

The road map needs to outline a process through which the following will be identified:

• Where the organization stands (Status Quo)

• Whether the organization reached its learning objectives

• The means of building an Innovative culture

• How value will be delivered

There are three pillars which support our innovation platform roadmap (learning, innovation, and value delivery).

A gap analysis was done to evaluate the learning environment status quo. Then an Innovation strategy was developed based on the following elements:

Leadership

The company’s top management should identify opportunities and challenge the wisdom of the crowd. Market trends and opportunities represent innovations in the market in fields that could benefit the firm, such as lean construction, building information modeling (BIM), sustainability, work face planning etc. and defining who is responsible for the high-level planning of development of the Innovation Platform.

Rather than relying on a few experts in the company to solve specific innovation problems, you open the process to all employees (exploiting large numbers of diverse problem solvers). Crowdsourcing (Henri & Tuomas, 2014) requires fast and efficient ways to test many potential solutions.

The crowdsourcing method was selected after years of experience with Experts sourcing, and the first innovation platforms attempt was based on about 100 experts nominated by top management. This platform lasted for a few months and did not deliver serious innovations.

As there is evidence that groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers (Hong & E., 2004), we later decided to open the Innovation Platform for all our employees (to utilize wisdom of the crowd). This strategy succeeded in bringing together younger generations, who are enthusiastic to share their innovative and new ideas with their colleagues in the organization.

Change Plan

The adoption and culture change plan starts with people and operations, not technology and tools. We have planned for change by communicating the urgent need for a corporate learning platform, to establish a culture of learning that leads to innovation. In mega-construction projects (such as construction of pipelines, refineries, airports, power plants, etc.), engineers are located at construction sites and sometimes in remote areas.

It is highly recommended to brand the innovation platform or initiative and design a logo that makes a good image; design moves things from an existing condition to a preferred one (Graser, 2000). The name and the logo should be meaningful and represent the vision of the Innovation at the organization; brands are important, intangible assets that significantly impact firm performance (Park, Eisingerich, Pol, & Park, 2013).

Developing the Learning (Knowledge Management) and Innovation Platform requires resources and budget; many questions come from management and future users:

• Where will the change lead us?

• What will be achieved at the end?

The full picture should address the return on investment (ROI), the status quo and the future status. Performance evaluation is an important aspect that should be considered during the planning phase, to demonstrate decision makers’ added value and money savings.

The development of the knowledge management and innovation platform objectives include:

• Using the latest innovations and technologies

• Reducing employees’ effort to learn and Implement

• Recognizing the best performers

• Preparing future experts

• Preventing re-inventing the wheel

• Educating clients on the importance of innovations

• Delivering on time

• Spending on R&D

The corporate cross project platform needed to be developed to meet the above objectives. Those objectives were explained through direct communication with decision makers and involved parties. The objectives were communicated to employees in the implementation phase, to encourage participation and buy-in.

Innovation in Lifecycles

Innovation differs in every business sector, and it is affected by regulations, cultures and markets. Construction is a diverse field, and there is no standard pattern in which innovation occurs. The meaning of Innovation to a small, specialized sub-contractor is certainly different to that of an international enterprise construction contractor (Abbott, Ozorhon, Aouad, & Powell, 2010).

Building and construction contractors’ operations are mainly specialized in one or more categories: construction, engineering, design, surveying, consulting or management. Therefore, the organizational context of construction innovations differs significantly from a great portion of manufacturing innovations (Slaughter, 1998).

In the context of the construction industry, (Slaughter, 1998) breaks down the spectrum of innovation into five types: incremental, modular, architectural, system and radical. Incremental innovation is a small change, based upon current knowledge and experience.

Modular innovation entails a significant change in concepts within a component, but it leaves the links to other components and systems unchanged. Architectural innovation, on the other hand, involves a small change within a component, but it involves a major change in the links to other components and systems.

Radical innovation is an entirely new approach and causes major changes in the nature of the industry itself. Contractors mostly apply incremental and modular innovations, due to the risky nature of the pipeline construction industry.

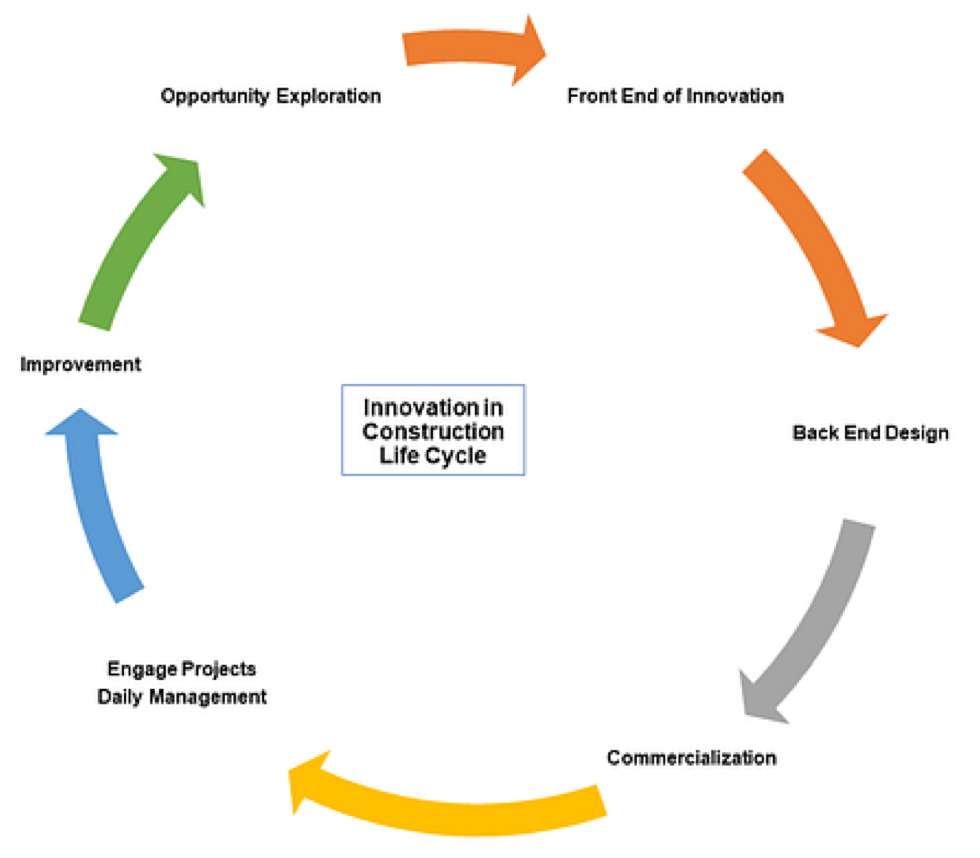

Innovation in the construction life cycle, similar to industrial innovation, starts from opportunity exploration, where market trends, client insights, technology trends, data analytics and regulatory and competitor information all play an important role in directing projects or contractors to investigate new innovations.

On the front end of innovation, we study project needs, if a new tool, method or technology is identified. We consider whether the innovation is suitable, usable and scalable. We also carry user experience tests and consider whether the project team will be able to sustain using this new innovation.

During the back end of design on the corporate or the project level, aspects such as usability, serviceability, robustness and manufacturability and assembly are considered. In Commercialization culture, change and leadership that are required for continued operational excellence are applied.

Daily management, project engagement, training and project team engagement should be highlighted in this phase, while reporting and innovation implementation progress monitoring are applied. The final phase is improvement, where lessons learned from applying this new innovation are evaluated and innovation evolvement is investigated.

Implementation

The innovation platform was created as a tribe of communities of practice (CoPs), as part of the KM collaboration platform, and it uses the wiki for capturing, storing and reporting new ideas and opportunities.

It operates outside the normal scope and boundaries of a single project. Each CoP was formed in an Agile approach and directed by the company’s top management. Each CoP has a leader (who plays the role of product owner), manager (who plays the role of an agile coach) and about 5–10 captains (experts from different areas).

These captains were selected by top management and the Innovation Communities leaders. Captains may change from one year to another. To integrate innovation with business processes, project team engagement is required.

We encouraged project teams to take part in suggesting new industry innovations, and any employee can suggest an idea openly. On a yearly basis, new innovative ideas are evaluated by the innovation tribe communities’ captains in order to prepare a business and visibility study for each idea. Then, evaluation is conducted again after the study is prepared.

Those innovations that meet certain criteria are selected to move forward. A Development and Implementation plan is then prepared, after forming a new CoP from experts in the field; this CoP will communicate with the projects and implement the new innovation. This process follows the rules of the innovation in construction life cycle discussed earlier.

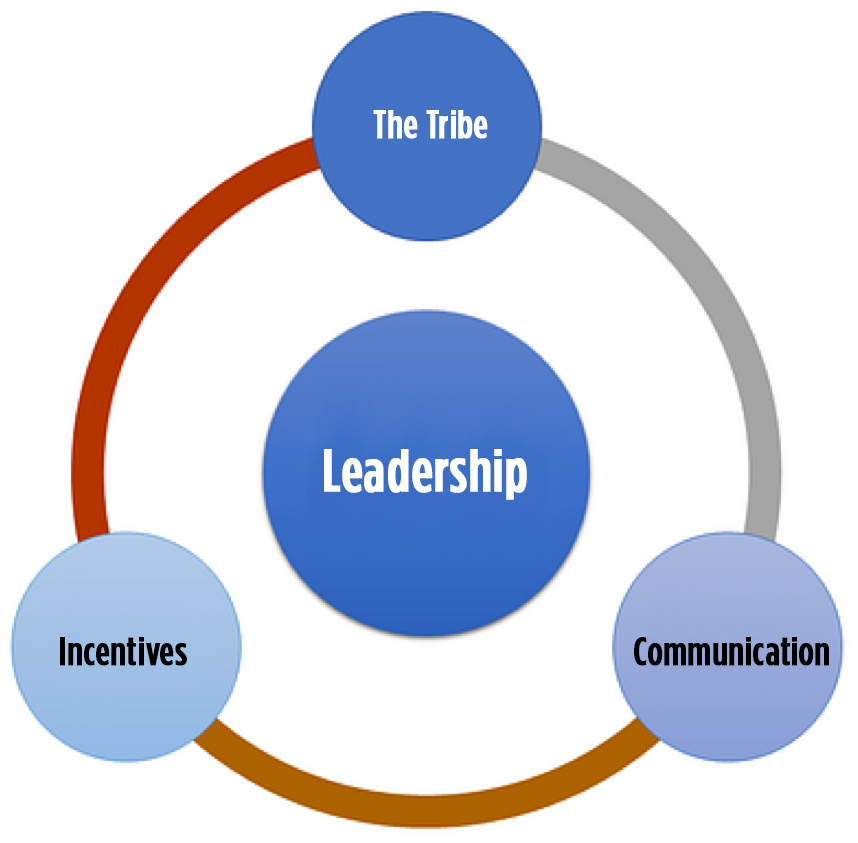

Leadership is a key success factor, as the company top management had to endorse and take part in the innovation platform, as well as have a budget to support the implementation of new innovations. Innovation initiative subcommittees have to report the implementation and findings to the top management, demonstrate the ability to move forward and discuss difficulties and challenges openly.

Top management, in turn, is tasked with addressing the challenges and eliminating the problems. For example, if the client does not approve of the new technology or work method, top management has more political influence and better relationships with the client that they may be able to leverage to convince the client to accept the new change.

The Sociotechnical framework was developed because of the interrelatedness of social and technical aspects when implementing innovations in construction projects (Duodu & Rowlinson, 2016).

A sociotechnical perspective seeks to understand the successful (or unsuccessful) diffusion of an innovation — not just in terms of the technical features of an innovation or how the innovation process is managed — but in terms of the myriad different social influences that bear upon the innovation process (Lees, 2018). Users and society play an active part in “socializing” a technology. This can be particularly important for pipeline construction companies.

For example, applying new surveying technology using Unmanned Arial Vehicle (UAV) might have reduced the number of surveyors needed. The potential positive effect (for the company) of applying this new innovation on performance is high, as it reduces time and cost.

Meanwhile, this is a highly sensitive issue with surveyors, as many of them might lose their jobs, so addressing this consequential issue in a fair and open manner is essential for adoption. During the pilot project of implementing the new innovation, we faced cultural rejection, as it was very clear that the surveying team was not fully cooperating with the implementation team.

After discussion with the project manager, we decided to educate and encourage surveyors to use the new technology, by training them and demonstrating that the surveying effort required in the office, using the new technology, will be at least equal to surveying effort spent on the construction site, using traditional methods. Once we gained some supporters, we were able to sustain the change.

Another example of sociotechnical perspectives is applying a new safety radar system to heavy vehicles on a construction site. The radar system detects moving objects and creates a hazard zone, so that the operator of the vehicle will be aware of any moving objects, through a camera and warning alarm.

The system improved safety on the job site, but we also noticed that employees became more relaxed when moving, as they knew the vehicles were equipped with a radar system. Consequently, they were supportive of the innovation. Employees’ behaviors and routines have a key role to play in how a technology is used and, therefore, whether it is successful or not.

As we saw in the previous examples, we have to create a communication platform by using online collaboration tools, to show successful examples of the implementation of new ideas, as well as to connect employees from different projects to share innovations and experiences.

Many of those employees will be part of the innovation tribe, as they will take part in suggesting new ideas and help with implementation. Incentives are also important. Those employees who endorse innovation, share their experience and knowledge and volunteer their time need to be rewarded and recognized.

In most cases, staff members belonging to different functional and hierarchic areas take part in the innovation processes, and this highlights those who are particularly creative, those who make decisions, or staff members who have specific professional know-how.

Sustaining Innovation

Most innovations happen here because most of the time, we are seeking to get better at what we’re already doing. We want to improve existing capabilities in existing markets, and we have a pretty clear idea of what problems need to be solved and what skill domains are required to solve them. But we have to say that on a journey of innovation, not every idea is possible to implement.

For example, flying drones in many countries involves strong legislation and regulations to adhere to. There are formal rules which dictate what can and cannot be developed. There are also informal rules; for example, professionals such as engineers, architects and surveyors learn particular approaches to problem solving, use a common language and often have a clear idea of what is expected of them professionally.

These informal rules shape problem solving approaches, or heuristics, which guide the innovation process as strongly as the formal rules do. Groups who share the same heuristics are referred to as technological regimes. These technological regimes guide and shape the innovation process in a particular direction, giving the regime a momentum which we call a technological trajectory (Lees, 2018).

To overcome the technological regimes, we established the sociotechnical framework discussed earlier, where a larger group of employees gets involved in the innovation outside the bubble of a single project team.

The sociotechnical framework is important for implementing and sustaining the innovation platform, and it is based on traditional methods and change management tools. Traditional methods include setting an innovation road map and including it in the company’s strategic plan, in addition to preparing a yearly R&D budget.

Change management tools include communication and awareness, awards and recognition and training. When applying new methods or tools, you need to train people on site, as they are used to doing the job for many years using an older method or tool. Training should be on all levels and results should be evaluated.

Evaluation

Ongoing performance evaluation highlights whether the objectives are met and what the weaknesses are. Below are the key performance indicators (KPIs):

• Innovation growth: Lessons learned, collaboration, questions, and new ideas shared.

• Learning curve: Employees’ engagement in discussions and membership and performance in innovation subcommittees.

• Review and evaluation of objectives on monthly and yearly bases, what was the effect of the new work method/tool/procedure?

• Refine the objectives based on the evaluation, for instance if there is an environment which rejects an innovation let us find out how we can convince people to use the new technology.

• Evaluate employee’s acceptance and response to the change.

CONCLUSIONS

When applying new innovations in mega-construction projects, the risk gets higher, so construction contractors become more conservative in applying any new method. This challenge made us think about how to connect innovation to projects and how to get buy-ins and project teams on board.

This was achieved through an innovation platform that connects employees from different projects to share their innovations based on their experience in the project. So, our approach was not to tell people what to do, but rather to listen to them and understand their desires and needs. People should feel personal achievement in order to be part of the innovation success.

Building a culture that encourages innovation, where people feel that management listens to their suggestions, encourages people to endorse any new innovation and help with implementing it successfully.

Knowledge management collaboration and communication tools are important to connect people across projects, as they will exchange experiences and lessons learned. Virtual communities have proved vital in achieving a culture of innovation.

References:

Abbott, C., Ozorhon, B., Aouad, G., & Powell, J. (2010). Innovation in Construction: A Project Lifecycle Approach. Salford Centre for Research & Innovation, 978–1–905732–86–9.

Benbya, H., Passiante, G., & Belbaly, N. A. (2004). Corporate portal: a tool for knowledge management synchronization. International Journal of Information Management, Volume 24, Issue 3, ISSN 0268–4012, 201–220.

Dickinson, M., Cooper, R., McDermott, P., & Eaton. (2005). An analysis of construction innovation literature. 5th International Postgraduate Research Conference, (pp. 14–15).

Duodu, B., & Rowlinson, S. (2016). Intellectual Capital and Innovation in Construction Organizations: A Conceptual Framework. Engineering Project Organization Conference (EPOC2016).

Freeman, C. (1989). The Economics of Industrial Innovation. MIT Press, Cambridge.

Graser, M. (2000). Art is work. Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press.

Henri, S., & Tuomas, A. (2014). A network perspective on idea and innovation crowdsourcing in industrial firms. Industrial Marketing Management, Volume 43, Issue 3, ISSN 0019–8501, 400–408.

Hong, L., & E., S. (2004). Groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers. PNAS,101 (46), 16385–16389.

Kuczmarski, T. (1996). Innovation: Leadership Strategies for the Competitive Edge. Lincolnwood, IL: NTC Business Books.

Lawrence, P. R. (January 1969). How to Deal with Resistance to Change. Harvard Business Review.

Lees, T. (2018, 01 09). Construction innovation. Retrieved from Designing Buildings

Mansour, O., Abusalah, M., & Askenäs, L. (2011). Wiki-based community collaboration in organizations. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Communities and Technologies (C&T ’11) (pp. 79–87). New York, NY, USA: ACM.

Park, C., Eisingerich, A., Pol, G., & Park, J. (2013). The role of brand logos in firm performance. Journal of Business Research, 66(2), 180–187.

Sexton, M., & Barrett, P. (2003). Appropriate innovation in small construction firms. Construction Management and Economics, 21, 623–633.

Sexton, M., & Barrett, P. (2004). The role of technology transfer in innovation within small construction firms. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management,11(5), 342–348.

Slaughter, S. (1998). Models of construction innovation. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Vol. 124, №3, 226–231.

Tangkar, M., & Arditi, D. (2004). INNOVATION IN THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY. Civil Engineering Dimension.

Xue, X., Zhang, R., Wang, L., Fan, H., Yang, R., & Dai, J. (2017). Collaborative innovation in construction project: A social network perspective . KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, 1–11.

Yamazaki, Y. (2004). Future innovative construction technologies: Directions and strategies to innovate construction industry. Proc.21st Int. Symp. on Automation and Robotics in Construction, IAARC. Jeju, Korea.

Comments