October 2015, Vol. 242, No. 10

Features

Egypt Gas Find Sparks Panic in Israel about Israeli Reserves

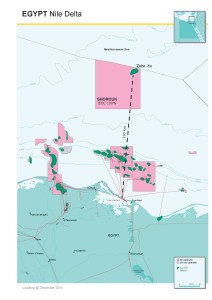

Italian major Eni, on Aug. 30, announced the discovery of a supergiant gas field in the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Egypt. The Zohr field is estimated to hold 30 Tcf of natural gas (5.5 Bbbls oil equivalent), though Eni believes more could be found. As it stands, the potential reserves represent the largest discovery in Egypt and the Mediterranean, topping Israel’s 16-Tcf Leviathan field.

For Egypt, the find is nothing short of a game changer. Domestic natural gas production has fallen some 16% since 2013 and exports are down roughly 70% since 2009. Conversely, domestic energy consumption is up more than 50% over the last decade, leading to widespread blackouts and social unrest.

Production in Egypt isn’t declining for a lack of gas. Instead, fuel and electricity subsidies, together with gas payouts more than 60% below the international average, have drained government coffers, limited investors’ revenues, and stalled previously promising projects. Though Eni – after securing higher gas prices from Egypt in June – is ready to fast-track development.

Eni CEO Claudio Descalzi sees drilling beginning in 2016 with production commencing shortly afterward. Peak output may reach up to 3 Bcf/d, or roughly 68% of current production.

Eni will likely sell most of the fuel into Egypt’s domestic market, said a spokesman. With a minimum development period of at least four years, it would be about 2020 before any production started in the Shorouk block. Eni said it planned to appraise the field and start “fast track development.” It didn’t provide a time line for the project in the statement.

A” find of this size should be enough to cover a lot of Egypt’s energy gap,” said Robin Mills, a Dubai-based analyst at Manaar Energy Consulting. “They’ll likely have to meet domestic needs first, before any export plans are discussed. This will also put a damper on Israeli plans to export gas to Egypt.”

And, indeed, news of its neighbor’s natural gas bonanza has caused an uproar in Israel, with energy stocks plummeting and recriminations over indecisiveness and infighting that have delayed production from the country’s own gas fields.

The government continues to struggle to get parliament to approve its natural gas business plan, but observers fear Israel may need to reassess everything now that Egypt, which had been cast as both an export destination and a partner, may have found its own independent solution. Israel’s offshore gas reserves had long been regarded as a future cash cow for the resource-poor country, and gas exporters in Egypt were expected to be the key customers of Israel’s yet untapped Leviathan field.

But plans to develop Leviathan are suddenly up in the air after Eni’s discovery in a field that is located in shallower seas than Leviathan, likely making it easier for companies to extract, in a country with none of the regulatory chaos of Israel.

“It adds a whole new layer of uncertainty to an already very messy situation,” said Gal Luft, an energy security expert and senior adviser to the United States Energy Security Council. “It essentially postpones any prospect for a deal.”

Israel discovered two large fields, Tamar and the larger Leviathan, in 2009 and 2010, raising hopes that the gas would reduce Israel’s dependence on foreign sources of energy and create a new engine for the economy. But exploiting the gas has turned out to be more complicated than anticipated, amid repeated disputes over pricing, export policies and how to split profits with energy companies developing the fields.

Egypt’s massive gas discovery “is a painful wake-up call for our really foolish conduct,” Israel’s energy minister, Yuval Steinitz, told Israeli Army Radio. “For years we have been stalling the searches, stalling development. Nothing is moving.”

For months, Israeli leaders raced to clinch a deal to lure developers to extract Israel’s gas. But the deal has been held up as critics accused Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of caving in to a monopoly at the expense of Israel’s coffers. Even Israel’s antitrust commissioner opposed the deal.

Israel’s Cabinet tried to sidestep the commissioner by claiming the gas deal was a matter of national security since it involved business ties with Egypt, the first Arab country to make peace with the Jewish state and a key ally in the battle against Islamic militants. But now that Egypt has struck liquid gold, Israeli leaders worry that developers will have less incentive to develop Israel’s resource at all.

Opposition lawmaker Shelly Yachimovich, a leading critic of Israel’s deal with the gas companies, said the Egyptian gas discovery would likely introduce more competitive prices to the market and, therefore, Israel should not rush into a deal promising high profits to developers, siphoning off funds that could benefit the Israeli public.

“If the discovery is real, there will be regional competition, prices will drop. So it’s absolutely clear that we must not get trapped now in draconian contracts,” she told Army Radio.

A partnership between Texas-based Noble Energy Inc. and Israel’s Delek Group is the main developer for Tamar and Leviathan, and also owns two smaller reserves discovered recently. The firms have been selling gas to the Israeli market from the Tamar field, which went online in 2013, and have agreed to sell to neighboring countries as well.

The heftier Leviathan field, which until the Egyptian discovery was considered to be the largest gas field in the Mediterranean, has not yet been developed, pending assurances from the Israeli government about the profits the companies will be allowed to reap. Initially scheduled to go online next year, it now remains unclear when the field will be developed.

The developers were counting on sending Leviathan’s gas to Egypt, where there are facilities to liquefy the natural gas for export to Europe. Egypt’s proximity to Israel and the longstanding diplomatic relations between the two countries would have facilitated that.

After long negotiations, a government committee struck a deal with the firms earlier this year, aiming to break up their monopolistic control of Israel’s gas reserves and introduce competition while maintaining incentives for fresh investment. But Israeli environmentalists and opposition lawmakers say the deal maintains the monopoly and squanders Israel’s resources. Their calls for more competition have helped delay a vote on the plan.

In another setback to the deal, Israel’s economy minister, who has the authority to override the antitrust commissioner, changed his mind and will no longer sidestep the opinion of the commissioner. That brings Israel back to the drawing board, because the antitrust commissioner resigned amid the controversy and his replacement has not yet been appointed. The deadlock, coupled with Eni’s announcement, forced Netanyahu to call off a planned vote in parliament.

“While here we are busy with infighting and how to make sure nobody profits, the state of Israel could already have signed export agreements that could have brought in billions of shekels,” said Uri Aldubi, chairman of the Association of Oil and Gas Exploration Industries in Israel to Army Radio. “The window of opportunity for the Israeli gas industry is quickly shrinking. Now is the time to make haste and promote the development of Leviathan and the search for additional sources.”

While Israel continues to debate the deal with gas developers, Egypt is projecting a willingness to do business and gas developers may abandon Israel for Egypt, said Luft, who co-directs the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security, a Washington-based think tank focused on energy security.

Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi has staked his legitimacy on fixing the economy, and in a country that frequently suffers from blackouts, he has made energy projects a priority.

But Israel can still find other buyers, Luft said. He said Cyprus and Greece would be good markets because they use oil for electricity, and natural gas would be a cheaper alternative. He also proposed that Israel adopt a different method of exporting natural gas by compressing it, instead of investing billions of dollars in building the kinds of liquefying plants that Egypt possesses.

According to Descalzi, if fully developed, Egypt would not have to import gas for at least 10 years. Count Russia among the players who hope that kind of success does not transpire.

While Russia’s shifting global tendencies have been dubbed a pivot eastward, economic and political realities have shown the pivot to be far from discriminatory. Russia cares little if Germany or China, or neither meets demand needs – just, that they are met. Toward that end, Russia has also been eyeing North Africa, more specifically, Egypt. With its rapidly growing oil and natural gas consumption and stumbling domestic production, the country was supposed to be a promising, long-term market. It still is, but for different reasons and for different parties.

In March, Russia’s Gazprom and Egypt’s Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company (EGAS) signed a 5-year LNG supply deal. Per the agreement, Gazprom is to deliver seven LNG cargoes per year – the first of which was already received. More recently, Rosneft signed a similar 2-year, 24-shipment LNG supply agreement with EGAS to begin in October. The deals will be fulfilled – and Egypt’s entrance into Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union promises further cooperation in oil and nuclear capacities. But, long-term, the Zohr discovery limits Egypt’s potential as an export market and may cause problems for Russia further downstream.

In 2013, essentially the country’s last year of meaningful exports, Egypt exported 130 Bcf of LNG. 79% of those exports sailed east to South Korea, Japan, China and other markets in Asia, while, Europe, once the country’s primary export destination, received a miniscule 130 Bcf. Those aren’t exactly fear inducing numbers for Russia – 130 Bcf is roughly what Russia sent to Austria in 2014 – but Egypt was supposed to be a customer, not a competitor.

To be sure, Egyptian exports are unlikely to explode on the scene anytime soon; 2020 remains an optimistic target under current domestic supply and demand trends. But, even a modest return to form – say 2011, when Egyptian LNG accounted for 5% of EU-28 LNG imports – presents some headaches for a Russia fighting to maintain or expand its market share on all fronts. Moreover, continued delays, and a general lack of enthusiasm for Russia’s Turkish Stream pipeline, favor the ever-expanding and ever-competitive field.

Part of the output from the Egyptian field could be shipped to Italy or other destinations as LNG, Descalzi said. Eni is a partner in a chilling plant at Damietta on the Mediterranean coast. The facility hasn’t been operating for lack of gas, Descalzi said.

Eni is looking to divest some of its peripheral businesses as a drop in global oil prices puts pressure on earnings. The company has asked advisers to look at options for assets, including interests in Nigerian oil and gas fields. In March, Eni became the first major oil company to announce a dividend cut after prices slumped.

Egypt is the first foreign country Eni expanded into from its home base in Italy in 1954. The Rome-based company already produces gas in Egypt and is a partner in a venture operating a gas liquefaction terminal at Damietta on the Mediterranean coast. Descalzi led Eni in its largest natural gas find at the Mamba field in Mozambique, where the company has found 75 Tcf of gas in the offshore deposits of its Area 4.

Comments