February 2016, Vol. 243, No. 2

Features

Storage Site Leak Raises Environmental, Reliability Concerns

Southern California Gas Company (SoCalGas) detected a major leak Oct. 23 at Aliso Canyon, an underground natural gas storage facility located 30 miles northwest of Los Angeles. The Aliso Canyon storage facility, which has 115 wells, is the second-largest natural gas storage field in the western United States.

The 86 Bcf of working natural gas capacity at Aliso Canyon accounts for two-thirds of SoCalGas’ natural gas storage capacity, according to EIA data. Additionally, Aliso Canyon has the largest daily deliverability of all the storage facilities west of the Rockies, estimated at 1.9 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d).

Stopping the leak is proving to be a major engineering challenge. SoCalGas has already employed several strategies to plug the well. The failure of initial efforts to control the leak led to the decision in early December to start drilling a relief well that would intersect the leaking well at a depth of about 8,500 feet and then be used to kill it (in other words, permanently seal the well). As of Jan. 25, the relief well had been drilled to a depth of 8,400 feet, but the drilling rate is expected to slow during the final approach to intersect the leaking well.

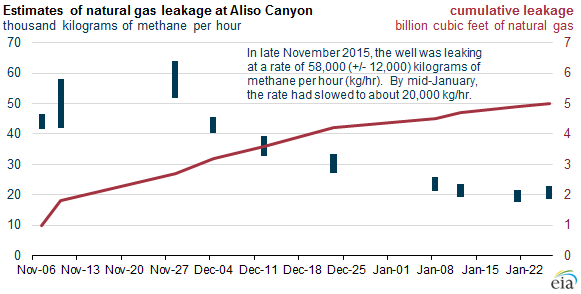

SoCalGas has also prioritized natural gas withdrawal from the facility to reduce pressure. In late November, the well was leaking at an estimated rate of 58,000 kilograms of methane per hour (kg/hr); that rate has slowed to about 20,000 kg/hr as of Jan. 26, the latest available data. The Governor’s Office of Emergency Services in California is regularly issuing news about the leak, including the progress of the relief well.

The primary constituent of natural gas is methane, a colorless and odorless gas. Because the leaking natural gas had already been through a processing plant prior to storage, it contains small amounts of the putrid-smelling gas mercaptan, which makes natural gas leaks more easily detectable. Although both the offices of the South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD) and the California Health Hazard Assessment have described only limited health impacts related to the leak, SoCalGas has paid to relocate thousands of residents near the storage site after complaints of headaches, nosebleeds and nausea.

Methane is also a potent greenhouse gas. Methane makes up a relatively small share of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, but it has a global warming potential (GWP) estimated at 28-36 times greater than carbon dioxide (CO2) over 100 years. As of Jan. 26, the California Air Resource Board (CARB) estimated that the site has leaked 5.0 Bcf of natural gas, which is equivalent to 2.8 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, assuming a GWP value of 28.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s emissions inventory for 2013, the latest available, reports total U.S. GHG emissions of 6,673 million metric tons in CO2-equivalent terms. Global warming potentials are based on the amount of energy certain gases can absorb and how long those gases stay in the atmosphere. CARB and SCAQMD are monitoring methane emissions daily.

The leak at the Aliso Canyon storage facility could also have implications for energy system reliability in the region it serves. Natural gas storage plays a critical role in meeting natural gas demand on peak demand days. For Southern California, storage withdrawals are at their highest level from December through February, but there are also summer days during which natural gas is withdrawn from storage to fuel electricity generation.

While the immediate priority is stopping the leak, energy companies, system operators, and government officials are also interested in the leak’s potential reliability implications during the upcoming periods of high natural gas demand (this summer, next winter), and in identifying possible actions to mitigate any reliability concerns.

It is not yet clear how much storage capacity will be available at the Aliso Canyon facility, and in what timeframe, once the leak is stopped. This level of capacity will depend, in part, on what further actions will be needed to assure the integrity of other wells at the facility, of which roughly one-third are similar in age and design to the leaking well.

Principal contributors: Michael Kopalek, Perry Lindstrom

Comments