May 2016, Vol. 243, No. 5

Web Exclusive

Why $50 Oil Is Here To Stay

Now that oil prices have rebounded to $50 per barrel, will U.S. shale drillers turn the taps back on?

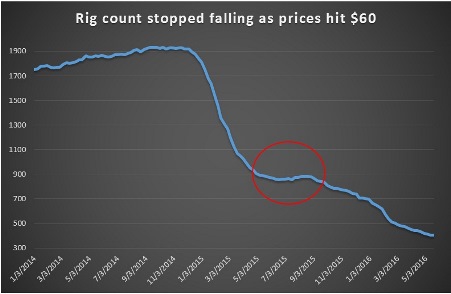

That is the million dollar question that the oil markets still do not have a clear answer on. Last year, when oil prices rebounded from $44 per barrel in March to $60 in June, the rig count leveled off. Some drillers even redeployed some rigs, stepping up drilling ahead of what they believed would be a swift rebound in prices.

The renewed drilling spooked the markets and crude plunged again, and since August of last year, the rig count has been falling, shedding another 400 to 500 rigs in only nine months.

Now that crude prices have firmed up at around $50 per barrel, will the rig count rebound again? Will prices build on their momentum, and move closer to $60 per barrel? And, perhaps most importantly, can drillers make money at today’s prices?

There are a multitude of variables that will determine the how fast drilling starts to pick up. But one of the most important metrics to look at is the breakeven cost of drilling in some key U.S. shale regions. According to a report from KLR Group, and reported on by Oil & Gas 360, many of the most prolific shale basins in the U.S. are still in the red at today’s prices.

For example, the Eagle Ford West breakeven price sits at $59 per barrel and the Eagle Ford East has a breakeven of $52 per barrel. Meanwhile, the Bakken, another major source of U.S. oil production at over 1 million barrels per day, has a breakeven price at a whopping $67 per barrel, meaning many drillers in North Dakota are still losing money.

Even some of the best parts of the Permian Basin in West Texas have higher breakeven prices than many believe. The Midland Basin, for instance, which offers some of the best economics in U.S. shale oil production, has a breakeven price of $51 per barrel.

Image courtesy: Oil and Gas 360

The story is similar for natural gas production – breakeven prices could be much higher than is popularly cited in the media. For example, many parts of the Marcellus Shale, which accounts for the bulk of U.S. shale gas production, has breakeven prices at around $3.50 per million Btu (MMBtu), vastly higher than today’s Henry Hub spot prices of less than $2/MMBtu.

Image courtesy: Oil and Gas 360

In short, the KLR study finds that most oil and gas regions need much higher prices to provide companies with a financial return. In order for companies to generate a 10 percent unleveraged rate of return, the Midland Basin and the Eagle Ford East will need oil prices in the range of $80 to $85 per barrel. And those are some of the best places to drill. The price needed for a 10 percent unleveraged rate of return only goes up from there. The SCOOP/STACK plays in Oklahoma require oil prices near $100 per barrel.

Many individual companies have reported lower breakeven prices than these, but by and large, the KLR Group report shows that shale drilling economics may not be as rosy as some believe. Some might question the validity of this data, and to be sure breakeven estimates run the gamut. But, if the industry could make money in U.S. shale at $40 or $30 then there would not be more than 70 shale companies that have declared bankruptcy. If breakeven prices were that low, the rig count would not have collapsed by 75 percent in 18 months, nor would U.S. oil production have ground to a halt and then plummeted by nearly 1 million barrels per day since last year.

Clearly, prices are substantially too low for many drillers to make money. As a result, despite predictions from the EIA and others that oil prices could stay low for much longer – the EIA expects WTI to average $50 in 2017 – prices are still unsustainably low. If drillers can’t make money at $50 per barrel, supply will continue to fall, triggering a rise in prices. In short, prices must rise.

Companies began drilling last year as oil prices hit $60 per barrel on the expectation that further prices gains were in the offing. But many drillers may not be so willing to jump back into the fray this time around, at least at first, if only because there is a lot less certainty over the solidity of the rebound. That will lead to further declines in U.S. supply, which, again, will push prices much higher than $50 per barrel.

Comments