February 2018, Vol. 245, No. 2

Features

Guideline Shows How to Make Oil And Gas Industry Cyber-Secure

By Petter Myrvang, Information Risk Management, DNV GL, Oil & Gas

Digitalization is bringing great benefits to the oil and gas industry including pipelines, with even more gains to come from the smart use of data through advanced data analytics. Advanced data analysis is paving the way for greater operating efficiencies and better safety and sustainability performance.

More than a third (37%) of more than 800 senior oil and gas professionals surveyed by DNV GL started 2018 expecting research and development (R&D) projects in digitalization to receive the go ahead this year.1

A similar percentage (36%) see R&D in cybersecurity as likely to win approval in 2018, and 43% expect their organizations to increase spending on cybersecurity this year. Digitalization and cybersecurity are by far the leading R&D categories in our survey. Looking at the next five years, 75% of respondents say they will invest in digitalization, and 68% in cybersecurity.

In the pipelines segment of the oil and gas value chain, for example, gas transmission system operators (TSOs) are tracking or acting on advances in artificial intelligence, the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), machine learning and augmented reality to achieve safer and more efficient operations.

Some are beginning or planning to integrate digital technologies into more sophisticated data gathering, analysis and visualization systems to maintain, repair and operate their gas networks.

Connectivity Risks

With the gain comes potential pain. Greater connectivity between operational technology (OT) and information technology (IT), and the rise of the IIoT, increases the cyber-vulnerability of oil and gas systems.

All elements of pipeline systems available remotely or from the control room could be targets for malicious cyber-attacks, including pipeline safety, protection or other control systems. Right along the chain from wellhead to consumer, the spread of cyber-physical systems raises the security challenge.

As with physical attacks, cybersecurity breaches can lead to lost production; raised health, safety and environmental risk; costly damages claims; breach of insurance conditions; negative reputational impacts; and loss of licence to operate.

Pipeline owners and operators are reluctant to publicize cyber-attacks and the operational consequences for fear of inviting even more. However, attacks are increasing in volume and sophistication in the oil and gas industry, including pipelines. Cybersecurity is moving up the agenda for pipeline owners, operators, relevant industry associations, and governments and their agencies.2

Vital to Focus

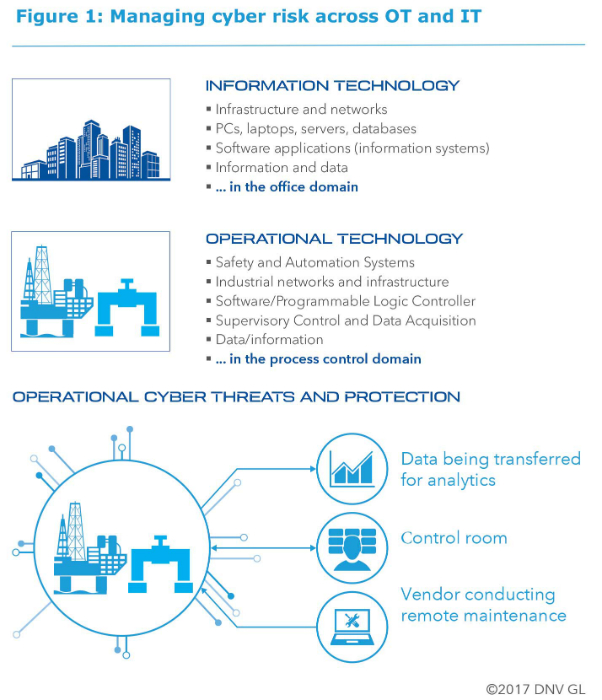

The key point in securing oil and gas assets against hackers is that critical OT network segments which were once isolated are now being connected to IT networks, which potentially makes OT such as supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems, safety and automation systems (SAS) and control systems with programmable logic controllers (PLCs) more vulnerable to hackers (Figure 1).

A Ponemon Institute survey of oil and gas professionals responsible for securing or overseeing cyber-risk in the OT environment found 59% believe there is greater cyber-risk there than in enterprise IT.3

Managing cyber-threats to OT requires knowledge beyond general IT security. Such knowledge includes traditional oil and gas operational domain competence as well as automated, unmanned, integrated and remote operations which are accessible online.

DNV GL Guideline

Confronted by the OT/IT cybersecurity challenge, parties responsible for the safe and sustainable operation of oil and gas assets including pipelines need to take a holistic approach. They can find out what to do by consulting the International Electrotechnical Commission’s IEC 62443 standard covering security for industrial automation and control systems (IACS).

However, until late 2017 there was no guideline available to explain to oil and gas industry companies how to implement IEC 62443, tailored to their sector.

Seeing this need through its own work with customers on cybersecurity, DNV GL initiated and led a two-year joint industry project (JIP) to develop a globally applicable recommended practice (RP) to address how oil and gas industry operators, working with system integrators and vendors, can manage the emerging cyber-threat.

The industry partners in the JIP were ABB, Emerson, Honeywell, Kongsberg Maritime, Lundin, Shell Norway, Siemens, Statoil and Woodside Energy. The Norwegian Petroleum Safety Authority observed the work and exchanged experiences with the JIP group from a regulatory perspective.

The result is the recently launched and downloadable “Recommended Practice DNVGL-RP-G108 Cybersecurity in the oil and gas industry based on IEC 62443.” It also embraces international practice and experience and considers health, safety and environmental requirements as well as the IEC 61511 standard for specification, design, installation, operation and maintenance of a safety-instrumented system.

DNVGL-RP-G108 is not only for new installations, existing and older ones may need to be updated with respect to the new risk picture in the new, connected reality.

While the RP focuses on the concept, front-end engineering design (FEED), project and operation phases of greenfield and brownfield projects in the upstream sector, it is also relevant for the whole oil and gas industry including the midstream and downstream sectors.

Ethical Hacking

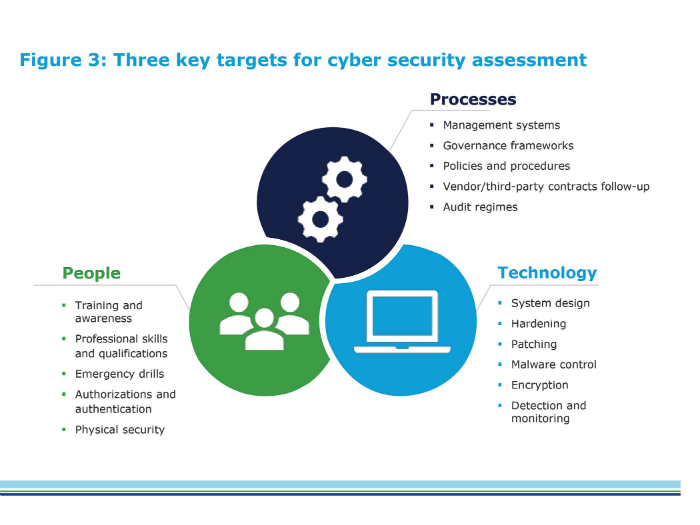

The RP is intended to include all the elements – people, processes, technology – that are involved in ensuring cybersecurity are taken care of in the IACS (Figure 3). This includes the asset owner, system integrator, product supplier, service provider and compliance authority. The RP clarifies the responsibilities shared between these parties and describes who performs the activities, who should be involved, and the expected inputs and outputs.

Sometimes, the best defence is to subject an organization to a simulated attack. Under the ‘technology’ heading for assessing and ensuring cybersecurity, some companies including DNV GL recruit and develop “ethical hackers’ to do just that through testing and verifying OT, IT and linkages between them.4

DNV GL’s ethical hackers combine hacking expertise with profound domain knowledge of OT. Knowing what can be done if a hacker gets control gives ethical hackers a better idea of what to look out for than someone with purely IT experience.

They start with passive and active reconnaissance of the cybersecurity of assets or systems – remote-metering infrastructure for example. They then scan for potential vulnerabilities. If they find any, they next try to gain access through penetration testing so that they can reveal vulnerabilities to help customers mitigate them.

Vulnerabilities can be simple, such as the use of default system passwords; missing patching; and, unsecured Wi-Fi providing a route into control systems. Ethical hackers also scan customer OT and IT systems for vulnerabilities that could be used to enter and exploit the system to affect operations or access confidential information. Some of this scanning and testing is carried out remotely over the internet from DNV GL’s centers of expertise.

Technical Qualification

Ethical hacking can also assist the verification and technical qualification of equipment and systems. DNV GL is experiencing increasing interest from operators and vendors in testing – including ethical hacking – for cyber-vulnerabilities as part of the company’s longstanding verification services.

Indeed, penetration testing is a relevant third-party verification step for any critical cyber-enabled infrastructure. Addressing cybersecurity right from the concept phase, third-party penetration testing activity can then be used to validate the effectiveness of the barriers that were initially designed into the integrated system.

In response to rising demand in the energy sector, the company established a new DNV GL Technical Assurance Laboratory (DTAL) in 2016 with the techniques and tools to detect device flaws as part of a product security evaluation service currently being applied in the sector. This service includes applying ethical hacking techniques to products.

Keeping Up Standards

Cybersecurity is an ever-changing landscape and knowledge base, requiring continual updates to standards as threats ebb, flow, and change.

The IEC62443 committees are expected to issue a new standard for protection levels (PLs) at some point in the future, for example. Protection level is a methodology for evaluating the protection of plants in operation. It includes the combined evaluation of technical capabilities and related processes, and of technical and organizational measures. The technical implementation and configuration in the IACS, and how the IACS solution is operated, maintained, and deployed will be reflected in the PL.

DNV GL intends to update DNVGL-RP-G108 on a regular basis as industry and standards go forward, incorporating experiences and new developments. P&GJ

Author:

Petter Myrvang, head of Information Risk Management at DNV GL, has more than 28 years of experience in the oil and gas industry, dealing with a wide range digital technologies and practices. Since 2008, Petter has led the developments and implementations within the area of information risk management, to manage risks related to digitalization and the emerging use of digital solutions in the industry.

Comments