July 2022, Vol. 249, No. 7

Features

South Africa’s Fuel Switch and the Pipeline Market

By Shem Oirere, Contributing Editor, Africa

South Africa’s drive to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 would require huge investments in a phased fuel switch by industrial and domestic consumers, which could diversely impact the country’s pipeline market.

With the focus in the short- and medium-terms being toward the use of more liquefied natural gas (LNG) and hydrogen, the size of South Africa’s gas pipeline market is not likely to expand in size, but rather open new opportunities for the recalibration and reconfiguration of the existing pipeline network.

South Africa’s energy and chemicals group Sasol recently indicated it is moving toward that switch when it announced the approval of development funds to finance coal-to-gas conversion at its Secunda complex, which produces fuel and chemicals in the Mpumalanga area.

At the Secunda complex, the world’s largest coal liquefaction plant and the largest single emitter of greenhouse gas, Sasol uses the process to produce petroleum-like synthetic crude oil from coal using the Fischer–Tropsch process.

Switching from coal to gas would be a boost to Sasol’s plan to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions by 30% by 2030 while focusing on the use of hydrogen as a long-term solution to its energy supply needs.

Sasol CEO Fleetwood Grobler recently told media in South Africa the company has secured at least 30% of the financing it requires to fund the gas reforming capacity at Secunda.

Transitioning the Secunda complex from running on coal to gas would cost an estimated $1.3 billion (ZAR 20) to $1.5 billion (ZAR 23 billion), he said.

“I think this is a very important signal that we are now putting our money where our mouth is with respect to processing capacity and to prepare ourselves to be able to reduce our coal use in a phased manner,” he said.

Meanwhile, two leading business lobbies in South Africa, National Business Initiative (NBI) and Business Unity South Africa (BUSA), in conjunction with

Boston Consulting Group (BCG), said in a recent joint report that an evaluation they carried out of all gas supply options confirms liquefied natural gas (LNG) as the optimal strategic gas infrastructure pathway in meeting South Africa’s short-term to medium-term gas supply needs by 2050.

The LNG option “emerges as optimal for South Africa because of the socioeconomic benefits it yields, and the inherent flexibility to ramp down supply post-2040 and minimize the risk of stranded assets and gas infrastructure lock-in,” as reported in the joint report, dubbed “The role of gas as a transition fuel in South Africa’s path to net-zero.”

The LNG option, as noted in the report, would require a multihub development approach including exploring the investment in floating storage regasification units (FSRUs) at strategic locations, particularly Matola in Mozambique, Richards Bay, Coega and Saldanha in South Africa.

“In addition to Matola as a supply option, developing all the other three South African FSRUs in parallel, emerges as the optimal supply scenario for South Africa, given the higher socioeconomic impact and increased bargaining power for consumers, which will potentially yield a more competitive delivered LNG price,” as stated in the report.

The development of the three South Africa-based FSRU hubs in parallel, NBI projects “will require limited capital expenditure (capex), focused on the FSRU and port modifications, with a maximum FSRU capex of $3.3 billion (ZAR50 billion) across scenarios.”

Developing the FSRUs in the three locations would require custom-built or converted LNG carriers that are permanently moored at a sea island offshore jetty, according to Transnet Pipelines, formerly Petronet, South Africa’s State-owned pipeline network operator.

The FRSUs will be replenished by LNG carriers that moor alongside and transfer the processed gas via a cryogenic pipeline, which allows transfer of liquefied gas over long distances, to the FSRU storage tanks.

Transnet says the LNG will be re-gasified on the FSRU before it is transported from the facility to primary gas transmission pipelines to the market.

Despite the likelihood of the FSRU option being expensive in terms of the high operational costs, particularly on the long-term lease charges for the vessel and the limitations that comes with it in that it cannot be expanded, Transnet says the LNG pathway to reducing greenhouse gas emissions has other advantages such as the lower capital investment costs and the shorter time required to bring the facilities online.

The report analyzes other gas supply options open to South Africa, such as ensuring there is no additional gas supply, the piped gas and exploration

alternative particularly at Rovuma in Mozambique, the biggest source of supply of natural gas to South Africa, and at Brulpadda, where global energy giant Total SA made a significant gas condensate discovery particularly in Block 11B/12B in the Outeniqua Basin, 109 miles (175 kilometers) off the southern coast of South Africa.

However, the report noted that “Rovuma piped gas, in particular, is highly complex with significant political and security risks to be addressed (while) extracting gas from Brulpadda may also be technically complex, which could further increase the cost of these pathways.”

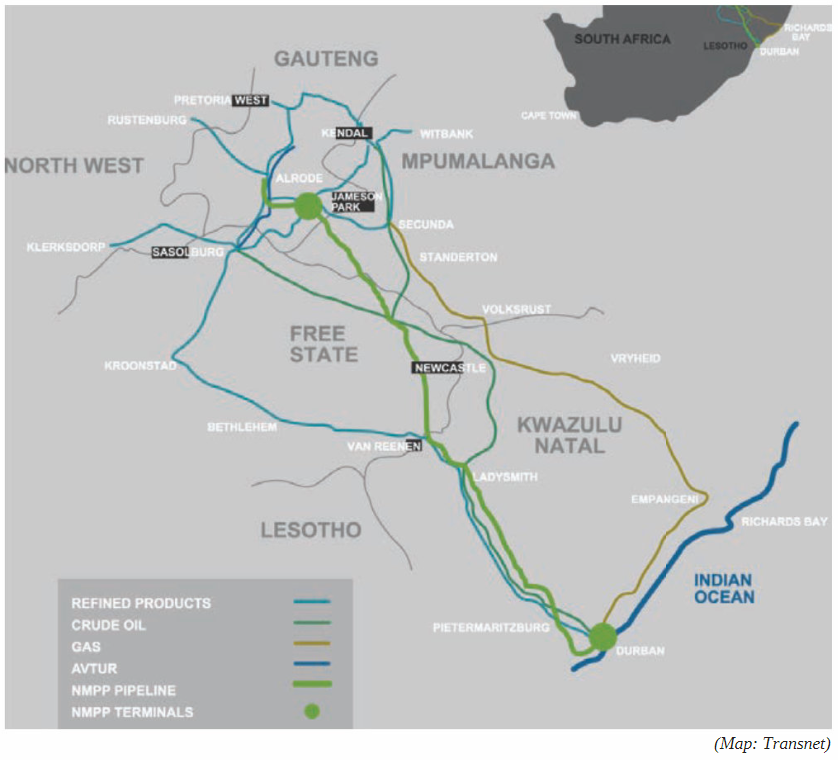

Currently, South Africa has an estimated 1,935 miles (3,114 km) of high-pressure oil and gas pipeline network operated by Transnet Pipeline, transporting an estimated 16 billion liters of liquid fuel and 450 million to 500 MMcm of gases.

The drive to scale up supply of LNG and hydrogen could diversely impact South Africa’s pipeline network.

Although the country produces a mere 2 metric tons of the global demand of hydrogen, all of which is grey hydrogen produced mostly from natural gas by Sasol, there is a push to produce more hydrogen, a move that would realign the use of existing gas pipelines.

According to the NBI, BUSA and BCG report, South Africa has potential to produce green hydrogen at a competitive price of $1.60 per kg by 2030 due to its excellent renewable energy resources.

Currently, South Africa is pursuing the implementation of the Hydrogen Valley project, a supply corridor that would start near Mokopane in Limpopo, where platinum group metals are mined, extending through the industrial and commercial corridor to Johannesburg and ending up in Durban.

The project provides opportunity for the modification and expansion of the existing gas-to-liquids facility operated by PetroSA, as well as the existing port infrastructure that runs from the east coast to the west coast of the country to supply hydrogen into the domestic and international markets, according to Bonginkosi Nzimande, minister of Higher Education, Science and Technology, when he launched the Hydrogen Society Roadmap on Feb. 17.

The Roadmap says with no extensive hydrogen supply network of “existing gas pipelines could be leveraged for hydrogen transport and distribution in the longer term.”

But the low demand for hydrogen in South Africa would mean the proposed hydrogen supply hubs of Johannesburg, Durban and Mogalakwena may not require new pipeline infrastructure because trucking looks to be a viable option in the short-term.

For example, in Johannesburg, the Roadmap shows transporting hydrogen by truck in liquid or compressed form, would cost between US$0.5/kg of hydrogen within the hub and $1/kg if extended to the Western Cape.

“Our analysis reveals that the hub does not have sufficient demand to justify building a hydrogen pipeline,” the Roadmap says.

Similar observation has been made for the proposed Durban hydrogen hub where transporting hydrogen by truck could cost between $0.1/kg of hydrogen and $0.6/kg; hence, the region lacks sufficient demand for construction of a new hydrogen pipeline.

The roadmap, however, proposes locating the green hydrogen supply sites “close to existing gas pipelines, keeping open the option of future possible injection.”

“In the short-term, investments in hydrogen pipelines in the hubs do not seem competitive given the limited hydrogen volumes at play in the first phase,” it observed.

For new hydrogen pipelines to make economic sense, the Roadmap said significant hydrogen demand is required.

For example, for 62 miles (100 km) of hydrogen pipeline, at least 2.8 tons/h of hydrogen is required while 4 tons/h of hydrogen. Similarly, South Africa would require a minimum of 6.2 tons/h of hydrogen for a new 310-mile (500-km) hydrogen pipeline to be viable.

The government recommended truck transportation, while the amount is still low, adding, “Transporting through truck also allows for rapid scale out without the need to build or rehabilitate pipeline and await regulation for hydrogen blending.”

Other recommendations that the South African government is working on include leveraging Johannesburg’s proximity to an extensive gas distribution network, including hydrogen pipeline from Vanderbijlpark to Springs, which “could be considered for hydrogen distribution with minimal technical upgrades.”

Furthermore, the Roadmap recommends locating the hydrogen supply site near Randvaal “to allow connection to pipeline to Sasolburg, along R59.” A similar site near Nigel would also allow “connection to pipeline to Secunda.”

The proposed Durban hydrogen hub currently had one transmission pipeline along the coast “that could be considered for H2 transport after technical upgrade.” The coastal supply sites in Durban have all been sited close to this pipeline.

With the shift toward LNG for generating electricity in South Africa and subsequently to hydrogen as the best option in the long term, the country’s oil and gas pipeline market is likely to create more opportunities for operation, repair and maintenance segments as demand for new gas pipelines reduces and the net-zero carbon emissions deadline draws closer.

Comments