September 2010 Vol. 237 No. 9

Features

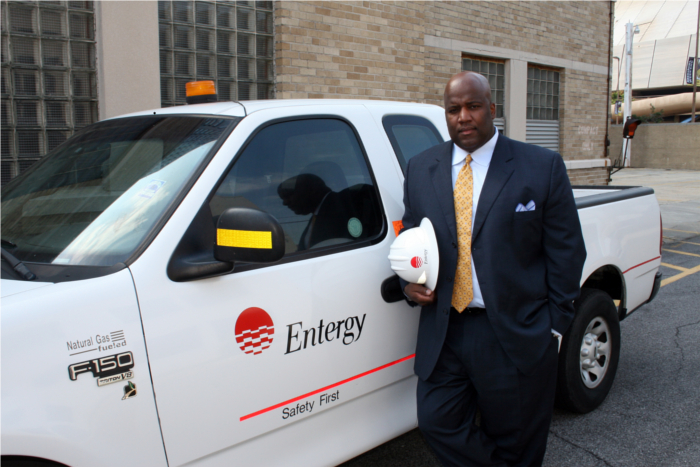

How Rod West Overcame the Challenge from Hell

Five years have passed since the monster named Katrina wreaked unprecedented destruction and death upon the grand old city of New Orleans.

A worldwide audience watched transfixed by horrific images of misery, destruction and death. Those who rushed in to provide emergency aid were left speechless by the scenes that greeted them.

Much of the city has recovered since the levees failed New Orleans in the fateful days after Aug. 29, 2005. With the possible exception of the San Francisco earthquake in 1906, the Galveston hurricane of 1900 and 2008 or the Chicago fire of 1871, no American city has such a devastated point of reference as New Orleans and hopefully none ever will again.

But what about those for whom New Orleans was and is home? How do you pick up your life again, much less think about the work that must be done?

Thoughts of Hurricane Katrina are never far from the minds of those who lived through the nightmare of those days and weeks. Even after five years, the memories hit locals at the most inexplicable times, serving as constant reminders of how cruel fate can be.

Today Katrina is also a testament to how strength, perseverance and hard work can overcome enormous adversity.

Rod West can talk to you about all of this, for he was there before, during and after well….just about everything.

When Hurricane Katrina barreled toward Louisiana, West headed Entergy New Orleans Inc.’s (ENO) electric distribution operations. On the morning of Aug. 30, West awoke with the realization that it was his job to marshal the forces necessary to restore electric service to the water and wind stricken city. It surely was not the type of job he envisioned 17 years earlier when he played for Lou Holtz’s 1988 national championship football team at Notre Dame, nor in the ensuing years where he practiced law at the Jones, Walker law firm in New Orleans.

“I am the embodiment of the maxim that life is what happens to you while you’re making other plans,” West said during an interview in his New Orleans office. The ground level floors of the office were raised several feet after the flooding waters swept through the building. Notre Dame memorabilia and plexiglas-encased commemorative Saints Super Bowl footballs have a prominent home on the front of his desk.

West is a tall, broad-shouldered, and barrel-chested man of 43. He sheepishly admitted that he was a few pounds heavier than his playing weight at linebacker and tight end for the Fighting Irish. However, he retains that football player’s grip, as one discovers after a hearty handshake that exudes both confidence and grace. On the day of this interview, he had been president and chief executive officer of ENO for three years. One month later, he would be promoted to executive vice president and chief administrative officer for Entergy Corp., the parent company of ENO.

“If you would have told me 12 years ago that I would become an executive in an electric utility, I would have made you take a drug test. Twelve years ago, my career path was geared toward what I hoped would be a successful legal career. You never underestimate the power of suggestion,” he said.

In January 1999, two of his former law firm colleagues, who were then in-house attorneys at Entergy, mentioned that Entergy was looking for an experienced litigator in the regulatory arena and suggested West consider leaving private practice for an in-house job. That’s usually not a hard decision, as many lawyers in private practice would jump at the chance to leave the often pressure-filled billable-hour world to take an in-house legal job. But in this particular case, the job was in the utility regulatory arena – challenging even in the best of times – and to make matters more interesting, the job represented a cut in pay. West’s move to Entergy represented a gamble that would pay dividends in more than monetary ways.

West joined Entergy in April 1999, and within six months Entergy suggested that he leave the practice of law altogether and move into regulatory management. It was an interesting time in the regulatory world of the electric utility. West would soon find himself immersed in the then proposed merger between Florida Power & Light and Entergy Corp, the natural gas crisis of 2000-2001, and the political regulatory environment post-open access (retail competition) leading up to the fallout from the Enron scandals. The landscape seemed to shift overnight. That period, West recalls, represented a tremendous learning opportunity.

In 2003, as part of a developmental assignment in electric distribution operations, West was named director of electric distribution operations for New Orleans. As if that wasn’t enough work, that same year, West enrolled in Tulane University’s Executive MBA program, launching one of the most intense learning periods in West’s career. On weekdays, he was broadening his exposure to the poles and wires side of the utility business. On weekends, he was honing his accounting, finance and management skills.

On Aug. 29, just two weeks after the then-37-year-old native New Orleanian graduated Tulane, Katrina struck, and West’s life and his city would change forever.

“All of our lives were turned upside down, inside out and ripped from its core,” West recalled. “In New Orleans, they like to say that their future is now; they are looking ahead and that Katrina is in the rear view mirror. But in reality, it is never very far away. The morning of Aug. 30, the day after the storm, was the only day in my career that I wondered whether I had made the right decision to join Entergy. But within a 24-hour period, I came to the realization that everything in my life to that date had to have prepared me for that very moment in time,” West said.

There was little choice. West and others faced the ultimate test of what a man or a woman is made of. When the sun emerged over the shattered city the Tuesday and Wednesday mornings after the storm, West faced the inescapable reality that the future of New Orleans was dependent on Entergy’s ability to quickly and safely restore the electric grid and gas service serving New Orleans. Without electricity to the city’s intricate network of pumping stations, New Orleans could not drain the billions of gallons of water necessary to start the rebuilding process.

The fact that West was no engineer and had only been with the company for six years didn’t matter any more than his discomfort with the uncertainty associated with the fact that 80% of his city’s land mass lay under water. What did matter was his ability to summon up every available resource and merge it with the skills derived from his experience and education: project and team management; leadership; decision-making; risk management, to name but a few.

“All of those life lessons I learned from peewee football through the MBA program were brought to bear when I had to tell my work force that they were homeless, then turn around and ask them to return to an environment of uncertainty and danger to rebuild the electric grid for customers we didn’t know would ever come back, for a company that was in bankruptcy. To build for a future that was at that very moment uncertain and bleak.”

“I had to embrace the notion that I was prepared for this challenge. Otherwise, the task was far too daunting to manage,” said West, whose own house suffered substantial wind damage.

That Wednesday, following the first helicopter tour of the devastation, West flew to his work force’s evacuation center in Baton Rouge. It was also the first opportunity he had to tell his wife and daughter that he was alive. After barely an hour with them, he traveled to the Jimmy Swaggart Center where his line personnel for gas, electric and back office had holed up.

Entergy has standard emergency restoration plans for major storms that result in employees evacuating to a predetermined location and then returning, based on damage, to begin repairs. “Naturally, the workers were all extremely anxious about their homes and literally ‘chomping at the bit’ to begin the restoration process,” West said.

These were anything but normal circumstances. Communications systems were down and information was at a premium. Employees were eager for information.

“I had to inform them that, for about 75% of them, everything they left behind at home was gone and under water. It was at that moment that I understood the distinction of having the authority that comes with being in a leadership position, and the awesome responsibility that comes with it. From that moment on, we were responsible for the livelihoods and the mere existence of the people who were in our charge.

“That was a defining moment for me, both personally and professionally. That’s a scenario I’m sure played out across our company, industry and the region,” West said.

Five years later, West can afford to let loose a deep breath as he vividly recalls his employees’ courageous efforts battling to manage through and recover from the chaos.

“It would almost sound like a cliché to say they were courageous and heroic. But courage does not represent the absence of fear; courage is manifested when you acknowledge your fear, move forward and perform anyway. When the term ‘first responder’ is used in the context of a disaster, or an emergency, never is the face of a gas or electric utility worker at the forefront of that conversation. Make no mistake about it, in the darkest of the dark days of Katrina, the men and women of Entergy were there. In the days that followed, we were there.”

“It was the flow of electrons and of gas molecules through a system that we rebuilt and restored that allowed New Orleans to begin its recovery. At the time, we knew there would be no recovery of New Orleans if we had not done what we did to make service available.

“Working around power lines is inherently dangerous during normal circumstances. Following Katrina, the job was almost unbearable, as civil unrest and desperation took over New Orleans. The sound of gunshots became almost routine. On more than one occasion, employees had to be pulled out of the city because conditions were out of control. Through it all, Entergy’s employees never wavered. They showed up day after day, putting aside their own personal hardships for the greater good of the community.

“Our sense of satisfaction came from knowing the great work we did under unprecedented conditions, not from the accolades that come along with it. Those men and women who went to work restoring electric and gas service to areas of this city and of this region – not knowing the plight of their own circumstances – they will always be heroes to me. I’ll be forever grateful for their confidence in us, their loyalty to me and to this company, and to the city.

“There were employees who eventually went to their homes and found loved ones deceased. We were not spared in any way, shape or form in terms of personal loss. But to a man and woman, they sucked it up and delivered in the face of that adversity.”

Service returned to New Orleans slowly at first and then in waves, depending primarily on the water level. ENO used a staged approach to restoration based on the extent of the damage, availability of resources, and the likelihood of there being an immediate need for demand of electric or gas service.

Entergy crews first gave priority to pumping stations, first responders, hospitals, military, and FEMA installations where service could be provided to the most people. Then they branched out as the population slowly returned.

“The areas that were less damaged were where we put our resources in first because that’s where people actually were. Contrary to public opinion at the time, we didn’t make political decisions as to who did and did not have power available,” West said.

Then they moved north from the river toward Lake Ponchartrain and then east, following as best they could the water levels before approaching the most devastated neighborhoods of Lakeview, Gentilly, New Orleans East and the Ninth Ward.

Ironically, that April prior to the storm, Entergy held its annual storm drill based on a scenario starkly similar to Katrina. West recalls an eerie conversation during the drill when a scenario was posed that saw ten feet of water throughout the city, the Mississippi River gulf outlet is flooded and he is at the command center in the nearby Hyatt Hotel.

West said he had an almost tongue-in-cheek response to the conference call that posed that prescient scenario.

“‘What in heck (the blankety blank) do you expect me to do? Or what is there to do if you’re telling me that there is 10-12 feet of water in some areas of the city? There is no damage assessment in that environment. My job, at that point, is to first protect the safety and welfare of my employees by getting them to safety.” All joking aside, that would be precisely the right thing – and the only thing – West could do under those circumstances.

Utility crews nationwide scrambled to New Orleans to assist in the recovery through the mutual assistance program. No matter what they saw on television, they were stunned beyond belief at what lay in front of them. To a man and woman, West said the reaction was one of “My God! I would not have believed this had I not been here standing here looking at it in real time.”

“They heard from television and other reports about flooding with eight feet of water, but when you’re standing at that house and looking at the level where that water line was in relation to you, and you’re seeing it in its full scope and scale, you have no point of reference to draw upon to put it into context,” West explained.

Today, West and others say Katrina “is in the rear-view mirror where she belongs” though never very far away from their thoughts.

“We’re looking ahead now. The outsiders can come to the city and see New Orleans for the work it has left to do, but those of us who never left absolutely marvel at how far we’ve come,” he said.

Officials estimate the city has between 325,000-350,000 residents, about 78% of the pre-Katrina population. Rather than discuss repopulation, they now emphasize growing their city from this point forward. It is indeed “the new normal” for the city, its businesses, its schools and its people.

“There is still a sense of loss in many ways. But what is possible for us is the opportunity to affect change on those many things we knew that we could and should do better. That’s what gives me the greatest hope for New Orleans,” West said.

ENO and Entergy Corp. chose to stay in the city, where their offices are several blocks apart. They knew the signal it would send to employees, customers and the rest of the country if the city’s only Fortune 500-based company relocated. In a more practical sense, they knew it was vital to the recovery that Entergy play a role in helping the city return.

Collectively, Entergy sustained well over $1 billion in damages from Katrina and Hurricane Rita, which followed in September. The cost for ENO exceeded $700 million, which put it in bankruptcy until May 2007, four months after West was named CEO.

The customers also came back, helped along by some creative efforts within the company, New Orleans City Council, various federal and state agencies and many non-profits. A federal community development block grant allowed ratepayers to save $200 million in costs that would otherwise have been passed on to a shrinking customer base and might even have prevented some customers from coming back.

ENO’s focus in 2010 is no different than it was in 2004-2005: providing safe, reliable power at the lowest reasonable cost while being environmentally responsible. In other words, it’s back to the basics, though perhaps being even more acutely sensitive to keeping costs as low as possible. That’s not much different from other utilities around the nation with the exception being that about 25% of Entergy’s customers – and about 40% within the city of New Orleans – live at the poverty level.

Entergy Corporation, the parent company of ENO, has long been at the forefront of battling for the well-being of its customers. It has lobbied the federal government for years to increase funding for the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which helps struggling families pay their utility bills.

Additionally, under the direction of Chairman and CEO J. Wayne Leonard, the company’s Low-Income Initiative has improved the flow of assistance funds to those in need, help customers better manage their energy use and break the cycle of poverty through education, job training and programs that enable individuals and families to move toward self-sufficiency.

“It gives me great satisfaction to work for a company with a conscience,” West said. “We’re not afraid to speak out when we see an injustice or fight for our customers and employees when they need a voice. And we walk the walk. We were the first utility to voluntarily reduce its carbon emissions, and such a commitment was unheard of in our industry at the time.”

Indeed, for nearly 10 years, Entergy has been at the forefront of the climate change debate. In 2001, the company made its first voluntary commitment to stabilize greenhouse gas emissions at year 2000 levels for 2001-2005. After successfully completing its first voluntary CO2 stabilization commitment, the company made a second five-year commitment to stabilize CO2 emissions from 2006-2010 at 20% below year 2000 levels. The company has already met that goal. Additionally, Leonard has personally lobbied Congress to pass comprehensive climate change legislation.

“We’re looking at the science and economics of climate change and are certainly assessing proposed cap-and-trade and energy legislation to ensure it effectively reduces carbon emissions and doesn’t unnecessarily raise electric bills. However, none of these issues are new for us at Entergy because we’ve led the industry and the nation from a utility perspective on reducing our carbon footprint a decade ago when it wasn’t widely understood,” West said.

“As we contemplate climate change, a company that is not paying attention to the financial impact of these (public policy) decisions on its end-use customers is not going to be in business too long. That applies to politicians who make laws as well as utility companies who make decisions about the cost implications of business strategies,” he added.

ENO is also heavily focused on a multi-year gas rebuild project designed to replace 840 miles of pipe damaged by salt water (see P&GJ April 2010 page 28). Regardless of its justification, any incremental cost increase associated with the rebuild has a disproportionate impact on a smaller customer base. As ENO builds redundancy into its system for reliability purposes, it is ever mindful of the costs to customers.

Cost also summarizes the comments ENO receives when it asks cost-sensitive customers for their top priority. For the utility, the biggest challenge is trying to close the eternal gap between the level of service customers’ demand with the true cost associated with that actual service.

“Safe, reliable power at the lowest reasonable price is synonymous with cheap. Most of our customers don’t make the connection between service and cost of service. We’re doing our best job for them when they’re not thinking about the bill. It’s only when the lights are out or the gas is not flowing that we register. For most of our customers, the conversation on climate change is one they are willing to have after they’re able to pay their bills and sitting in the comfort of their home or office,” West said.

During his operations experience, West has also come to some important realizations about the natural gas business.

“Natural gas is an integral fuel source and needs to continue to be a critical part of any utility’s portfolio of generating fuels. I don’t think natural gas is going anywhere in my or my child’s lifetime. The issue for us is diversification. We have the responsibility to mitigate the sometimes volatile nature of that commodity in terms of its impact on our customers’ lives. As long as we continue to rebuild and maintain our gas system in a manner that is safe, reliable and mindful of the cost’s impact on our customers, and is environmentally responsible, we’re holding up our end of the bargain,” he said.

Nothing, he said, impresses him more than the natural gas industry’s emphasis on safety and training. It’s something he would like to see other segments of the energy industry emulate.

“I’ve been really impressed by what I’ve seen in our gas employees. The predictability of the skill sets that employee has because of the training and the safety record of the industry is what I’d like to see replicated in the electric sector. Gas for me has been a wonderful example of what is possible from a safety and performance perspective.”

From the comfort of his office on the top floor of the Entergy building, West looks out and his sees his city bustling again. Where there was once 10 feet of water, he sees workers hurrying to lunch or afternoon meetings. He sees revitalized neighborhoods and downtown buildings rising. He takes pride knowing his role in getting New Orleans back onto its feet and looking to a brighter future again.

At 43, West already has experiences that most of us will never get close to in a lifetime, with a career that includes spectacular highs of winning a football national championship at Notre Dame and staggering lows of watching death and destruction in his own hometown. His formula through it all has remained the same: hard work, a thirst for learning and never-say-die attitude.

As he turns away from the window to get back to work, he glances at a Notre Dame game ball he was awarded and remembers what his coach Lou Holtz said time and again, “Success comes before work in only one place: the dictionary.”

Comments