September 2013, Vol. 240 No. 9

Features

Americas Repiping The Flanagan South Story

Aside from the scale, engineering, design, construction and safety challenges, any of which could define a pipeliner’s career, what really motivates Enbridge’s Flanagan South Pipeline executives Jerrid Anderson and Mark Sitek, is the idea they are part of a larger socio-economic movement across North America. They’re helping to allow domestic energy to fuel more of the load, backing out imported oil.

“I have a real appreciation for how important this project is for the United States,” Anderson told a listener being briefed on the $2.8 billion, 600-mile, 36-inch project that is scheduled to start construction shortly.

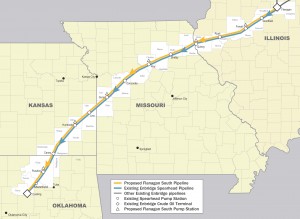

Starting at its existing hub at Flanagan, IL, southwest of the Chicago metropolitan area, the Enbridge project follows essentially the same corridor of the half-century-old, smaller-diameter Spearhead oil pipeline, cutting through southwest Illinois, northern Missouri, southeast Kansas and terminating at the storage processing center at Cushing, OK in the northeast corner of that state.

While the brownfield nature of the project has given Flanagan South a leg up, and financing is no problem with Enbridge’s deep pockets and strong commitment, the project has its challenges and chances to bring state-of-art equipment and processes to bear. Sitek and Anderson are readily willing to outline some of the advancements that represent the collective lessons learned for Enbridge and the industry from other mega-projects now in operation.

“This project is sort of part of the repiping of America,” said Sitek, with a mixture of pride and matter-of-factness. “Much of the pipeline infrastructure that we have had historically has been geared toward taking foreign crude and moving it around internally [in the United States]. With all of the increased production in Western Canada and the Bakken Shale play [in North Dakota and eastern Montana], the goal now is to move that North American crude to the refining centers on the Gulf of Mexico. This pipeline will be a key in doing that.”

In early June, Canada’s National Energy Board helped moderate two days of discussions on safety and the prospects for future regulation regarding large-scale pipelines. The top five Canadian pipeline companies, including Enbridge, were represented by senior executives before a packed house of industry, community and government officials.

Noting that a new level of reliability and safety is being crafted by major pipeline companies, Enbridge CEO Al Monaco said the industry is “making a jump from one that celebrates statistical success to one that strives for zero incidents.” As a result, internally, Enbridge has established a company initiative dubbed “Our Path to Zero,” a variation on a theme for most major pipelines these days.

“We took a long look in the mirror as a company,” said Monaco, who still smarts from the memories of a 21,000-bbl spill in the Kalamazoo River in Michigan in 2010 which took place shortly after the BP Mocando well blowout in the Gulf of Mexico.

The lessons learned over the years – good and bad – will be put in place in completing Flanagan South, Sitek and Anderson emphasized, noting that most of the line’s 550,000-bpd capacity has been accounted for after two open seasons and generally strong community support along the pipeline route.

“I am looking forward to having Flanagan South built safely, no one hurt and it being mechanically complete at a high quality level by its in-service date of July 1, 2014,” Anderson said. “We have learned a lot in our other large projects over the years [Alberta Clipper and Southern Lights pipeline projects, circa 2010], and we try to keep on getting better, applying continuous improvement. We can overcome most challenges a lot better as a result.”

In contrast to another large-scale Canada-to-Gulf-Coast project, TransCanada’s controversial Keystone XL oil pipeline, Flanagan has been flying under the national radar because it uses an existing pipeline corridor while Keystone is charting an entirely new route with its northern portion between Canada and Cushing.

“From our perspective there is room for both projects,” said Sitek. “Both have significant contract volumes, but with different customers, so from that standpoint they are mutually exclusive projects,” although both are focused on Cushing and subsequent paths to the Gulf refineries.

“This is a world-class project, 600 miles of large-diameter pipeline crossing four states, so it is a mega-project. That being said, Enbridge has done a number of mega-projects during the past several years. It is not the largest, but it is among the top four or five that we have attempted. We feel we have the expertise to execute it because we have done similar projects in the past.”

Construction has been broken into four spreads with about 500 workers overall for each spread, and at their peaks may total up to 600 workers a spread, Sitek said. In addition, there will be a number of workers at each of the seven pump stations along the route, configuring and eventually enclosing Enbridge’s unique collection of above-ground piping. Enbridge estimates employing 2,900 workers overall during the nearly year-long construction period. Ultimately, there will not be a lot of new permanent jobs, since Flanagan sits in an existing pipeline corridor with a ready corps of year-round workers who will be tapped to maintain and run the new pipeline.

“There are a lot of obvious efficiencies, so we won’t be staffed like the typical new Greenfield project,” Anderson said.

Besides construction jobs, Flanagan South’s biggest economic multipliers are about $27 million in property taxes it will pay collectively in the four states and another $72 million of sales taxes during construction.

Rights-of-way and permitting were still being worked out in late spring, but Sitek and Anderson expressed confidence that whatever else would be needed – such as 36 Osage Tribe land tract permits from the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs in Oklahoma and a U.S. Corps of Engineers permit – will be ready when the first trenches are dug.

“At this point in time, we don’t have all permits, but we’re on track to have all of them in hand by the time construction starts,” said Sitek, noting that earlier in the year Flanagan South had gained what he deemed a key permit from the Illinois Commerce Commission, a “certificate of good standing,” obtained ahead of schedule. “We have commitments from shippers for the majority of the capacity. We don’t disclose the names or the terms, though. There is also common-carrier capacity amounting to 10% that we have to make available.”

While the technology, techniques and equipment deployed for Flanagan South will be state-of-the-art and the level of training of its contract workforce at the top of the class, the topography and terrain will be the same as that encountered shortly after World War II when the Spearhead line cut its path from Illinois to Oklahoma. Illinois presents its own test because of its vast, rich topsoil topography that feeds its agricultural base. Kansas and Oklahoma present lots of sandstone that will require rock trenching.

“In the northern portion in Illinois, you have rich farmland with heavy topsoil, and that’s a challenge,” Anderson said. “We’ve undertaken that from a recent project working in Illinois. There are strict procedures you have to follow, and we have an agreement with the Illinois Department of Agriculture, with strict requirements we have to follow [in terms of restoring the topsoil to its original state]. We have to separate topsoil, but we’re used to doing that now.”

In Kansas and Oklahoma, Enbridge is planning on a lot of rock, anticipating a lot of trenching. “We will need a lot of blasting, and that is a little bit unique,” said Anderson, who classified Flanagan South as his biggest project, although in previous capacities he has been involved in other Enbridge large-scale projects.

About 10% of the routing deviates from the existing corridor. This occurs to avoid congestion in areas that have built up over the years: farm tracts, ponds, communities and cities where development has pushed close to the existing lines.

A major difference in the existing pipeline and Flanagan’s design is found in crossings. Where Spearhead has aerial crossings over ditches, rock and obstacles, Flanagan will be all underground, except for its seven pump stations.

For the industry, Flanagan South promises to provide some models in terms of training, quality control, materials, and the advanced technologies and equipment deployed. But the final story it writes won’t be finished until it meets its target in-service date in mid-2014, and it negotiates several key “gates,” or milestones, in Enbridge’s “lifecycle gating process.” Under this process, at each gate an interdisciplinary assortment of work units must sign off before the project can move to its next phase.

Flanagan South passed the “ready-to-construct” gate this summer but there will be other gates before it can pass through the final “ready-to-operate” juncture.

Enbridge will draw on a seven-year agreement with Russian-based global steel producer EVRAZ, which has North American headquarters in Chicago, for all of its pipe in Flanagan South as it has in other major projects since 2006. “It’s been a very great relationship in terms of the quality and availability of pipe,” said Anderson, adding that Enbridge has a detailed specifications agreement with EVRAZ that has been upgraded over the years.

EVRAZ bills its global operations as “a vertically integrated steel, mining and vanadium [a chemical element with atomic number 23] business with operations in Russia, Ukraine, United States, Canada, Czech Republic, Italy and South Africa. EVRAZ is one of the top 20 steel producers in the world, based on crude steel production of 15.9 million tons in 2012.”

Each segment is hydrostatically tested in the field, and from beginning (in the mills in Regina, Saskatchewan and Portland, OR) to end there are continuous inspections, Anderson said. The pipeline coating is checked alongside the trench and once the segments are in the trench. “We’ll have 190-200 Enbridge inspectors in the field overseeing the whole installation,” he said.

All of the welding will be automatic, mechanical, with skilled welders operating CRC Evans mechanical equipment as Anderson confirms that “pretty much the entire mainline” for Flanagan will be mechanized.

“Enbridge does this in any large-diameter pipeline, particularly where there are a lot of logistical issues and cross-country routes are involved. That’s when we’ll use auto welding processes,” he said.

All the 57 mainline valves will be remotely operated and controlled. Leak detection requires a “computation pipeline monitoring system” (CPM), which Enbridge has had for many years.

Another unique aspect is what Enbridge touts as a new standard design at the seven pump stations. The stations will have total above-ground piping – the only places along the 600-mile route where that exists – and the Rube Goldberg-like configurations will be enclosed by 20,000-square-foot structures.

“Should a leak occur at the station, with the above-ground, enclosed pipes, it could be readily detected and contained. That is how Enbridge is doing all of its pump stations now,” Anderson said.

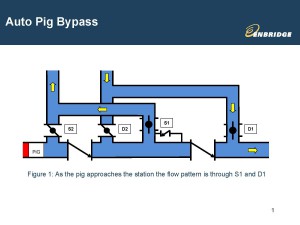

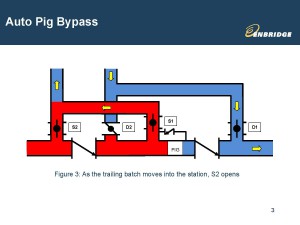

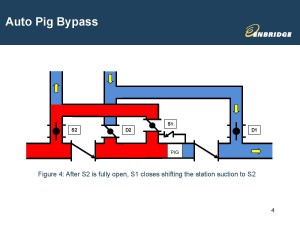

The pipeline will be batch pigged, according to the Enbridge engineers. “We’re putting pigs in the line in batches, and the facilities leaving the Flanagan terminal will have an auto-pig launching capability,” Anderson said. “Each pump station is designed to automatically bypass the pig.”

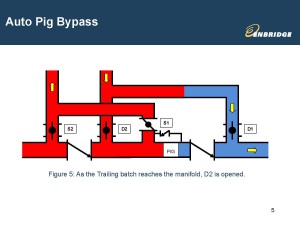

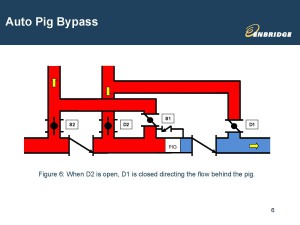

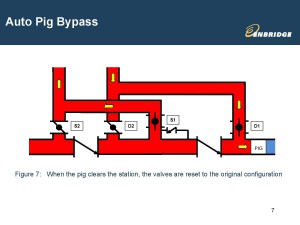

According to Enbridge, when pigs are used to separate the batches of oil, an auto-pig bypass system allows pigs to pass by a pumping station without being removed from the pipeline. Batch pigs can minimize mixing of the batches in the pipeline.

Other planned innovations for Flanagan include having two CPM systems. It has been using one of the systems for years – a material balance system based on oil volumes measured at different points along the pipeline.

“It takes into consideration the material line pack,” Anderson said. The second CPM system is pressure/wave based, using signals at all the valve sites, which will have pressure transmitters on them. “Should a leak occur, it uses pressure waves to identify the location.”

How does Enbridge characterize the built-in integrity aspects of this pipeline, compared to lines installed and operated earlier in this decade, or in comparison to the company’s mainline in Canada?

“We’re just building on our lessons learned from past mega-projects,” Anderson said. “This pipeline will be constructed with the highest quality and integrity. Through Enbridge, we try to have a quality management system that is overarching. All projects have their own quality plans.”

To support the quality assurance and safety, Enbridge sends its people through various levels of training. There are five programs, one that all employees go through and four more specialized training programs. It is computer-based training.

“One thing we’re doing now is putting professionals in the field that can look after quality and make sure our contractors are following procedures across all of our projects,” Anderson said. These specialists are both provisional contractors and Enbridge employees.

To get the project in service on its targeted start date of July 1, 2014 will take a total team effort, and it will also require much carefully planned and executed safety and testing steps. Anderson called them “standard things,” such as hydrostatic testing, post-construction coating surveys and running “caliper pigs” to measure pipe’s internal geometry, picking up imperfections, gouges, dents and any significant physical alteration of the pipe.

Flanagan will employ automatic ultrasonic testing (AUT) to identify any imperfections in the welds. Whatever advances the industry, generally, and Enbridge, specifically, have developed in recent years will be brought to bear on this project, Anderson said.

One innovation Enbridge has specifically targeted for Flanagan South is the use of geographic information systems (GIS). “They have been around for a long time, but with the use of high-speed Internet, anyone with the passcode to get into the Viewer can very quickly get into the details of this pipeline anywhere along its route,” Anderson said.

“The imagery, alignment, property information, all the environmental information – it’s all there at your fingertips. It’s incredible, everyone uses it – and it’s extremely accurate and is updated frequently throughout the day. All the spatial data is put into the GIS system.”

As Enbridge Engineers Describe The Process:

“This is how the batched pigs work: Prior to a pig entering the auto-pig-bypass, the valves are oriented in such a way that the suction is between the two check valves, and the discharge is downstream of the second check valve.

“When a pig enters the auto-pig-bypass it passes through the first check valve and the suction connection, then triggers sensors telling the process control system to initiate a pig bypass. The pig comes to a stop in a ‘parking area’ upstream of the second check valve.

“The suction and discharge values change position so the suction is upstream of the first check valve and the discharge is between the check valves, and behind the parked pig, pushing the pig out through the second check valve. The valves then reset to their pre-pig position.”

Richard Nemec is P&GJ’s West Coast correspondent. He can be reached at rnemec@ca.rr.com.

Comments