July 2021, Vol. 248, No. 7

Features

Williston Basin Petroleum Conference: Talking to Two Titans in the Oil Patch

By Richard Nemec, Contributing Editor

When billionaire oil man Harold Hamm travels to North Dakota to visit one of his favorite shale plays in the Bakken, he is sure to take a rifle and one of his favorite dogs. If prompted, Hamm will talk about his hunting dog and the litter of pups it recently fathered that “all look just like his beagle retriever.”

When he isn’t hunting pheasant with folks like Ron Ness, CEO of the North Dakota Petroleum Council, Hamm and the company he founded, Continental Resources Inc., are hunting for oil and gas in the Bakken and other unconventional basins in his native Oklahoma, the Rockies and elsewhere.

The thirteenth child of a sharecropper, Hamm in his youth picked cotton barefoot, worked in a gas station at age 16 to help support his family, and eventually with a high school diploma in hand started his own trucking company hauling water in the oilfields of Oklahoma before drilling his first well in 1971 with a loan he acquired at age 25.

By the 1990s, Hamm applied horizontal drilling in the Bakken region before it was a star among oil basins, and in the process, he is credited with helping transform the U.S. oil industry. Today, Continental, for which Hamm now serves as executive chairman with an 80% ownership interest, produces more than 330,000 bpd, most of it in the Bakken.

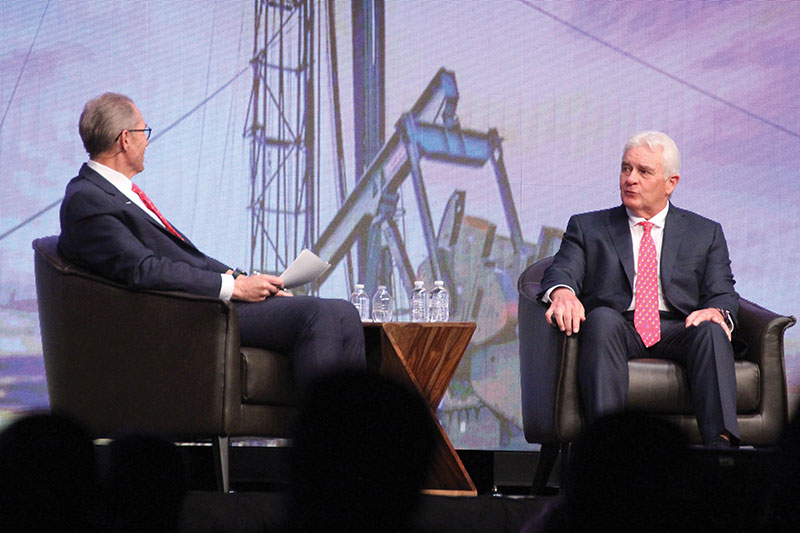

In mid-May this year, Hamm found himself back in North Dakota as one of the keynote presenters at the Williston Basin Petroleum Conference (WBPC), sitting on a stage with his buddy Ness and later listening to another fellow energy industry billionaire Kelcy Warren, CEO of the sizable interstate pipeline operator, Dallas-based Energy Transfer Partners LP.

Like Hamm, Warren is the product of humble beginnings in White Oak, Texas, where his father, Hugh Brinson Warren, worked for Sun Pipeline Co., a company now owned by his son’s Energy Transfer (ET).

He co-founded ET in 1995 with his partner Ray Davis, who is no longer with the business, but like Warren, is a billionaire. Younger than Hamm, Warren, 64, received a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Arlington in 1978.

At the WBPC meeting in Bismarck, Hamm and Warren appeared in separate sessions, answering questions from moderators who attempted to draw out these two energy industry titans for the 2,800 mostly in-person attendees at the annual conference which had reconvened this year after a pause last year in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Predictably, they are both bullish on their companies and the future of the Bakken, for which some analyses tossed around at WBPC estimate there could be more than 30 billion barrels of lifetime commercial production in the Bakken, in which 4-5 billion bbls have been produced thus far.

Warren, however, does not think there will be another $3.8 billion Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) interstate oil line built anytime soon, saying that the existing DAPL can easily double its 570,000-bpd capacity.

Both men are confident that the current legal fight involving the possible shutdown of DAPL while the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers completes a new environmental review will not result in closing the pipeline that takes most of the Bakken production to the Gulf Coast for export markets.

“There haven’t been a lot of interstate pipelines in recent years, and there are not going to be any for a number of years, unless there is some kind of event like the Colonial Pipeline incident [in early May],” Warren said.

DAPL effectively ended the large differential in prices for Bakken supplies compared to the Permian and other basins close to the Gulf Coast, so Warren thinks there will be a lot more gathering pipelines and processing infrastructure built, but no more major interstate pipelines like DAPL that moves through the Dakotas, Iowa and Illinois.

To the loud applause from the WBPC industry audience, Warren said, “We’re not shutting down Dakota Access; it’s not going to happen.”

Warren said he does not see how any of the additional environmental review will result in the 30-inch, 1,172-mile pipeline being closed.

“Can you imagine if we as a government start shutting down operating assets; I’m not aware of this anywhere else, so this just can’t happen,” he said.

In late May, a federal court decision denying opponents an injunction pretty much assured DAPL will continue to flow Bakken crude for the duration of the environmental assessment work.

Noting DAPL’s critical importance to Bakken producers like himself, Hamm thinks his friend Kelcy’s pipeline will withstand the challenges, and he calls the cyberspace hacking of Colonial Pipeline the work of international terrorists.

“These are foreign terrorists who want to take down America who are doing this,” Hamm said. “This sort of attack is very disruptive to millions of people. The midstream companies that we deal with are being hit every day just like we are at Continental. This involves terrorists, we have to treat it that way and get very serious about it.”

Calling Hamm a pioneer is not far-fetched given his track record in the industry’s modern transformation. With Continental he helped usher in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) as game-changers for U.S. oil and gas production.

More recently, during the Obama administration he helped lead an industrywide lobbying effort to remove the long-standing domestic ban on exporting U.S. petroleum products. And in the last year, Hamm has taken on the COVID-19 pandemic, refusing to lay off any Continental employees, preserving his corporate skill sets to allow the company to begin thriving again in 2021.

“We’ve got a whole different level of efficiency today than we had in the past,” said Hamm, labeling last year’s onset of the pandemic a “triple whammy” beginning with the OPEC fight between Russia and Saudi Arabia, followed by the COVID-19 and the bottom falling out of energy demand. “We had to rebound from it, but we’re back today, and Ron Ness did a great job in pulling all of his members together up here in the Bakken. As a result, we can make money at $55 a barrel oil today.”

During the pandemic, Hamm made the decision to keep all of Continental’s employees on the payroll. “We don’t dump our people in a downturn,” he said emphatically. “We need that skill set to focus on new opportunities. Our people don’t have to worry about their jobs.”

Regarding the now growing U.S. oil product exports, Hamm remembers seven years ago that a contingent from the industry had to convince the Obama administration to support their cause, and they eventually came around after what he describes as hundreds of meetings and trips to Washington, D.C., but only if it was made a part of the omnibus budget bill in Congress that year.

“We got it done, and we couldn’t have done what we have accomplished now without it. At that time, the differential for U.S. oil was way out of whack, like $27 a barrel, and that evaporated overnight,” he said. “It was gone.”

Many people in and around the oil patch want to know what guys like Hamm think about the prospects for “another Bakken” waiting to be tapped in the United States. He said it is possible, but it will not necessarily be within the footprint of the Bakken; he likes the northern Rockies in the Powder River Basin in Wyoming.

“We know there is still a lot of good drilling in the Bakken; we’re doing a lot of that right now,” Hamm said. “Even with all the drilling so far, this is still a magnificent play. Originally we didn’t have a lot of the technology we have today so there wasn’t a lot re-fracking or re-drills with the early wells.”

As a result, what is coming in the future is more enhanced oil recovery (EOR) work and secondary and tertiary recovery, he added.

“We’ve seen good results from these various technologies. And the good thing is that the future is out there for the Bakken, and we’ve got the technology and research to resolve any issues,” said Hamm, who contributed $10 million to the University of North Dakota for what is now the Harold Hamm School of Geology and Geologic Engineering.

Similarly, Energy Transfer and Warren have contributed $5 million to the University of Mary’s engineering school in Bismarck, N.D., as both he and Hamm remember their humble beginnings and are recognized philanthropists.

At the WBPC, however, Warren was genuinely puzzled by the recent Colonial Pipeline cyberattack, noting that Energy Transfer has experienced “several” electronic attacks in the past. The incident should remind Americans “how important pipelines are to this nation...I can’t wait to find out what actually happened in the Colonial incident,” he told his industry audience.

The supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) system on Colonial was unaffected, according to the company. “If you still have your SCADA, you can still operate for the most part, so that’s what I don’t understand in this case,” Warren said.

Damon Small, with the global cybersecurity firm NCC Group North America, argues for treating the computer systems supporting the oil and gas value chain as critical infrastructure with national security implications.

“Perhaps the computer systems that support these are far more important than we’ve given them credit for,” Small said. “It’s not just the convergence of operational and information technology, but IT itself that should also be treated as critical infrastructure as it relates to the energy supply chain.”

There were no substitutes for Colonial, NCC’s technical director for Security Small emphasizes.

“That one pipeline moves 2.5 million barrels of gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel per day. A tanker truck holds 190 barrels,” he said. “It would take about 13,000 trucks daily to replace the Colonial Pipeline.”

Pointing out that all of the legal action against DAPL is aimed at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Warren said emphatically that DAPL is not going to be shut down. He repeated his contention to an interviewer at the WBPC conference, Scott Hennen, host of a statewide radio talk show, What’s on Your Mind? in North Dakota.

Warren said that even with the change of administrations in Washington, D.C., DAPL is not going to be closed. It’s going to be business as usual.

“As soon as the [2020 presidential] election was over, I gathered my team to analyze what all of the vulnerabilities could be for the pipeline, and they said there was nothing to worry about,” he said.

Hennen added that the uncertainty created over the possible closure, however, is harmful to future energy infrastructure investment, and Warren agreed.

“It is a sad situation. I use the example of road building. Once a highway is built, is the government going to come along and shut it down?” Warren asked rhetorically.

In its nearly four years of operation, DAPL already has eliminated the significant price differential between Bakken crude and supplies from basins closer to the Gulf Coast, he and Hennen noted.

Hennen led Warren on a meandering 30-minute dialog on the state of the Bakken, the state of U.S. energy, political and consumer attitudes, and what’s in Energy Transfer’s strategic sights.

Warren kept a smile on his face the entire time, although he at times had some harsh words to deliver. Warren expects a lot of new gathering pipelines and related infrastructure to be built in North Dakota, but no long-haul pipelines for at least several years.

“I’m talking about crude lines,” he told Hennen. “Natural gas liquids and gas lines, sure, they’ll be built.”

Warren expressed admiration for the railroad industry, calling it the original interstate pipeline for transporting goods, “but rail can’t compete with pipelines.”

Before DAPL, three-quarters of the Bakken production was moving by rail, and Warren said his pipeline stopped that. (So far this year, about three-quarters of the Bakken oil production moves by pipeline.)

“Harold Hamm and others were getting about $20 a barrel less than a Permian Basin producer before DAPL,” Warren said. With increasing U.S. exports, Warren said there is no lack of “appetite for Bakken sweet crude globally; we have a quality product in the Bakken.”

Hennen described Warren’s job as “thankless,” but he thinks DAPL has been a “definite game-changer” for the people of North Dakota and energy consumers as a whole. Warren said the pipeline business is relatively simple and before DAPL he was struck by the fact that the second largest oil producing basin in the United States didn’t have a major takeaway pipeline. He saw it as a sad situation that Energy Transfer was lucky enough to be able to resolve.

Part of Warren’s current optimism for the industry stems from “where we were and where we are now” as both an industry and nation. In March 2020 as the pandemic raged, refinery utilization on the Gulf Coast had cratered from 97-98% to around 58%. “I don’t know a lot about the export market, but in the U.S. market, supply and demand are coming back into balance, and we’re into a recovery that I hope is slow and steady,” he said.

Energy Transfer is getting back to pre-pandemic levels of operations, but it is still not where Warren wants to see it. “We’re at 2019 levels, crude oil prices are back up, our NGL business is pretty good, our crude oil is so-so, and the spreads in Texas are around $1 a barrel,” he said. He likes natural gas, which the Bakken is producing at record clips.

Warren was asked about hydrogen, which is riding the hot trend line for future pathways to a carbon-free energy future, but he is not one of the converts yet.

“I have a rule at Energy Transfer that new proposals have to make economic sense, and hydrogen has something like 870 Btus,” he said. “However, I have told my team if you can bring me a solar project, wind project, or some other diversification that makes economic sense, I’ll consider it.”

Although neither Hamm nor Warren commented on it, North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum, a very successful entrepreneur, opened the three-day petroleum conference with a plea to industry leaders to pursue a goal of cutting the state’s carbon footprint by 30% by 2030.

Burgum called for the industry to embrace the global sustainability efforts summarized as “environmental, social and governance” (ESG) projects. The governor touted the goal as being good for North Dakota’s economic growth and good for the oil and gas industry.

Reiterating a slogan of “innovation, not regulation,” Burgum said. “ESG has become a major topic for everyone, and if you’re a public company it doesn’t matter if you make software or produce oil and gas, this is a board room topic around the world. This challenge also represents a great opportunity for North Dakota.”

As examples of work already underway in North Dakota, Burgum cited the state’s pursuit of produced water recycling in oilfields and EOR. Research is underway at the University of North Dakota’s Energy and Environmental Research Center (EERC) on both.

He sees the challenge to become carbon-neutral as “driving investment and consumer demand for products and services that have no or low-carbon footprints across every single industry.”

Ultimately, Burgum, the founder of various software startups, said the climate challenges cannot be solved without the innovations and expertise of the oil and gas sector. On that, Hamm and Warren surely would agree.

Richard Nemec is P&GJ’s correspondent based in Los Angeles. He can be reached at rnemec@ca.rr.com.

Comments