September 2014, Vol. 241, No. 9

Features

Traceability: A Technology, Requirement And Future For Pipelines

“The overriding lesson: great software can fail if it is not paired with industry expertise.”

– Brett Vogt, Project Consulting Services, Inc.

Whether they are people, places or things, there is nothing that can escape electronic scrutiny in the 21st century, pipelines included. With the right planning, personnel and software systems, both industry and government representatives agree that the tools are in place to maintain control and complete records for the North American, if the not the world’s, oil and natural gas pipelines.

It wasn’t always this way, and pipeline industry veterans certainly have changed their perspective on “traceability,” as industry and regulators call it, since the tragic incidents in San Bruno, CA and elsewhere in recent years. Those incidents highlighted the fact that inadequate recordkeeping practices still exist and may be contributing causes to incidents as a result.

For Metairie, LA-based Project Consulting Services Inc. (PCS), a pioneer in the electronic tracing of pipelines, recent changes in regulatory approaches embrace the company’s two-decades-old goal or mission. The newfound emphasis on traceability is the focus that PCS adopted in 1996 when the privately held company invested in the first version of its then groundbreaking software system, C.A.T.S.®

“If anything, the increased focus on traceability has allowed us to promote a viable solution to the industry instead of spending most of our time justifying traceability’s importance,” said PCS’s Brett Vogt.

Technology has carried PCS and the industry generally from where the very rudimentary version of C.A.T.S. was in 1996. Regulators and operators alike are more comfortable with where the industry is headed, given more stringent rules from the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), and a heightened awareness by pipeline operators.

The power of traceability cannot be overstated, particularly when it can help avert disasters like major ones plaguing the industry in recent years. On a recent project involving PCS, a mill identified potential problems with a specific coil of steel, and because C.A.T.S. was used on this project, PCS was able to locate all joints that were produced from that specific coil. The system uncovered multiple joints from the coil that had already been installed. Thus, PCS’s query and the tracking system allowed for the defective joints to be removed from the pipeline installation, along with preventing other quarantined joints from being installed.

With today’s technology, one hand-held device with an experienced technician can identify any pipe joints that have unresolved quality-control issues.

There is no such thing as business as usual these days. The competition is robust to keep up with technology and field-based operating innovations. Knowledge of pipeline field operations has never been more critical. This was underscored at PHMSA’s most recent Research/Development Forum for industry and government representatives to examine the industry’s national research challenges.

“PHMSA remains committed to identifying new ways to enhance the safety of the nation’s pipelines,” said Damon Hill, a Washington, DC-based spokesperson for the agency. “[The agency] encourages development of new technological advances that will assist pipeline operators in improving recordkeeping and reducing damages to pipelines from excavation. Over the past decade, PHMSA has invested approximately $69 million into research and development projects designed to address issues like more effective leak detection systems, testing for unpiggable pipelines, the development of stronger materials to construct new pipelines, and other technology improvements.”

Hill and other regional PHMSA officials contacted by P&GJ were reluctant to speak about specific technologies such as C.A.T.S. but like PCS and others in the industry, the agency is committed to pushing technology advances that can make the nation’s energy network safer and more reliable.

As a 40-year veteran of many pipeline construction projects, Buz Steele, a construction manager, can’t conceive of doing a project without a state-of-the-art tracking system. He goes back several years and several pipeline projects with the C.A.T.S. system, and while earlier versions may not have been perfect they made Steele’s life a lot easier, he said.

“It made my life in the actual construction [of pipelines] a lot easier just being able to know where any of your material was located at just about any given time,” said Steele, currently working on the ECHO Distribution System, through a unit of Gulf Interstate Engineering Co., which does a lot of work with Enterprise Products Pipelines. “It is tracked in every phase, and when you weld the two joints together, you know that has been done. You have traceability of your pipe at nearly all times, and the chances of getting the wrong kind of pipe in the wrong place are greatly reduced.”

It is the level of detail on traceability that has improved, Steele and others maintain. For example, on welds the information trail now includes: a number, date, installation contractor, type of weld, GPS location, weld procedure specification, procedure qualification report, welder(s) who performed the weld, qualification reports for approving the welder, the non-destructive examination (NDE) contractor who tested the weld, NDE test results, the NDE report, date and number, and finally, whether the weld was repaired or cut out.

In implementing tighter, more effective pipeline control and logging systems, field experience among the crews providing the tracking service and the construction/operation of the pipelines is critical. Veterans working with consultants such as PCS and with pipeline developer/operators, such as Kinder Morgan, reiterate this to anyone who is asking them about their jobs and the results of their projects.

“There is a lot of activity on a daily basis involving field people, mill, and back-office staff; it is a continual work in progress to maintain the material tracking database and ensure all supporting documents are linked to the pipe asset as the documents are received,” said Chris Heard, a PCS data coordinator and client services specialist, referring to one of the many pipe construction projects he has tracked for his company.

“We try to keep it as real-time as possible as things happen,” Heard said. “That way we can have accurate reporting back to the client [pipeline operator], and others on the project team.

“One of the main keys to our success with the [regulator and engineering] audits is the speed with which we can deliver the documents after they are requested. If you have a bunch of binders out there, you have to thumb through pages [of hard copy documents] and it takes a while to get these guys the right documents. The faster you can get the documents to the auditors the easier you prove that your project is successfully capturing all regulatory requirements.”

Russ English, a pipeline construction manager for Kinder Morgan, first encountered the advantages of traceable, verifiable pipeline tracking systems on his work overseeing Enterprise’s Yoakum-Howland, TX, NGL and residue pipelines. A work committee for the project decided to use PCS consultants and its C.A.T.S. system. Those consultants quantified and tagged all the material, loaded it into a data base and tied all of the data to the appropriate alignment sheets, he recalls.

Ultimately, the PCS team digitally and electronically filed all the project documentation that was quickly made available for inputting and monitoring on hand-held devices, English said.

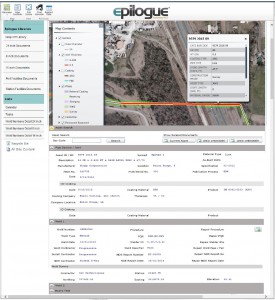

While it is common today on many projects and among a number of service providers, traceability or tracking was pioneered in the mid-1990s by PCS with its earliest versions of C.A.T.S. It has been enhanced by development of an electronic document management system, Epilogue™, and their eventual integration into geographic information systems (GIS) that are critical to state-of-the-art pipelines.

Epilogue™ provides a portal from which a user can request information from C.A.T.S. tracking system and all stored supporting documents simultaneously. And the same user can request this information through the integrated GIS, allowing the user to click electronically on a given asset and request data simultaneously from C.A.T.S. and the document management system within Epilogue. In other words, one click on an asset in a GIS map will execute a task in Epilogue, as will searching for an asset by its unique identification or weld numbers.

“Our vision always has been that records need to be linked to the specific pipe or asset to which they pertain,” Vogt said. “Technology advances have changed how we have implemented this task over the years.”

These are the electronic tools essential to any pipeline from the time it leaves the mill where it is manufactured to the time it is installed and ultimately hydrostatically tested to ensure its safety and reliability. While the mill operator never interacts with those steel segments once they are shipped, all of manufacturing data on the pipe joints are captured by C.A.T.S. at the time of shipment.

Typically, there is data on each pipe segment – seamless or welded – in addition to tracking pipe joints, valves and manufactured bends. There is information on each pipe joint regarding its manufacturer, its facility of origin, date and time of manufacturer, the source of its steel and any defects identified and noted at that time.

“We may also mobilize our personnel on-site [at the manufacturer] if there is not the capability to barcode the pipe at the manufacturing site, and in this case our job is to work unnoticed such that we do not affect the manufacturing process but simply perform our required tracking and barcode application as needed,” said PCS’s Vogt.

The barcode provides a proven method of uniquely identifying a given asset and allowing it to be captured or recorded at various points during construction without the potential for transcription errors. Integration of data into the GIS involves data that are collected on each asset and how the data model used allows for the C.A.T.S. tracking data to be easily transferred into common GIS models. PCS emphasizes that its comprehensive dataset is applicable to both GIS and document management systems.

Research in the industry continues to look for alternatives to barcodes, such as radio frequency identification devices (RFID), but the cost-benefits of this emerging technology still have not been proven for pipeline traceability. RFID tags cannot be read if the pipe has rotated to place the tag on the opposite side of the pipe from the RFID reader. Barcodes can be read at similar long distances to what RFID tags provide, and the latter cost 100-200 times more than barcodes, according to industry estimates.

On the other end of the process – testing the pipeline – the field operators doing the work usually know little, if anything, about the tracking process, but the electronic data they generate are vital to firms like PCS. Hydrostatic testing is an important link, but just one of the tests and documentation that a tracking system like C.A.T.S. captures.

In 2014, the challenge is to meld tracking data with pipeline operations data that is accessible down to a given segment across a vast geographic area. The pipeline historic data and the real-time operating data need to be stored and accessible simultaneously. Technicians at PCS view this as a part of the advantages of their C.A.T.S. and Epilogue systems.

There are other one-click systems available, according to pipeline professionals like Steele, but he adds that PCS led the way historically. And the PCS officials will stress that while it has some innovative software, the experience and lessons learned from using C.A.T.S. on more than 3,700 miles of pipelines is what gives it an edge.

“We certainly believe that we are employing great software developers to produce great technology, but the key to our success is that the design and implementation of our technology is guided by people who have extensive pipeline design, construction and operations expertise,” said Vogt.

The human factor comes into play when examining the abundance of data and information that modern technology allows to be collected efficiently and quickly. This presents a dizzying array of options and possible methods to be employed regarding traceability on pipeline. Field-experienced pipeline professionals are needed to determine what is critical and how best to present the vital information so it can be classified as “accessible and useful” to operators, regulators and other stakeholders.

As a company committed to solving the pipe tracking and record-keeping challenges, PCS touts itself as being founded in 1992 by what its current senior executives call “a core group of experienced pipeline engineers and project managers.” After first working in the offshore environment, PCS turned onshore with the initial development in 1996 of the first versions of C.A.T.S. Over the years, experienced pipeline veterans like Buz Steele have witnessed and encouraged continual improvements to a system currently operating in version 4.0 and vastly different from what was possible in 1996.

“C.A.T.S. was originally created as an in-house system for PCS personnel to use with our engineering and project management services to enhance the value of our existing services,” said Vogt, adding that the company’s core business is providing engineering and project management, but it has never provided inclusive engineering, construction, and procurement (EPC) services. Instead, it focuses on what Vogt calls “functioning as more of an owner’s engineer, supporting the pipeline operator” in the field and in the design/planning of major pipeline projects.

“One of our key technological differentiators is our use and integration [of C.A.T.S./Epilogue] with GIS,” said Vogt, noting that in the construction phase, an integrated GIS system displays asset data and also provides what he calls “a unique ability” to select an asset or joint and then “dynamically provide” key supporting documents linked to that individual asset.

Now on the fourth generation of C.A.T.S. and with the companion Epilogue software, PCS offers what Vogt describes as “data base enhancements” improving the GIS interface, field data collection process, all helping increase the overall speed and accuracy of the system. PCS has incorporated into version 4.0 of C.A.T.S. core lessons learned from past experience with the earlier versions of the software.

“We purposely spend time at the beginning of each project developing a comprehensive traceability plan with the entire project team, such that everyone understands the importance of traceability,” Vogt said. “Everyone involved in the construction of a pipeline project has a stake in the traceability and ultimate safety of the pipeline for its entire lifecycle.”

Richard Nemec is a Los Angeles-based contributing editor to P&GJ. He can be reached at: rnemec@ca.rr.com.

Comments