March 2012, Vol. 239 No. 3

Features

NACE Corrosion And Punishment Forum

NACE International—The Corrosion Society –holds its annual conference each spring, attracting 6,000 attendees and 350 exhibiting companies from around the worldwho represent every industry and technology for corrosion control. The five-day conference features an extensive technical program, meetings, lectures, forums, courses, networking activities, special events, and the largest corrosion exposition in the world.

In 2007, in response to several prominent corrosion-related pipeline failures and the recent ruling that the U.S. government is holding individual personnel—including non-management technical personnel—criminally responsible for such failures, NACE launched its “Corrosion and Punishment” forum at that year’s annual conference.

Chaired by longtime NACE member and 2012-2013 President Kevin Garrity of Mears Group, the forum has been revived by popular demand every year since its inception. Garrity and a representative panel of regulators and industry specialists provide forum attendees with the latest information on pipeline regulations, liability and enforcement issues, the importance of accurate recordkeeping, the latest in pipeline corrosion management programs, and more.

For CORROSION 2012, scheduled for March 11-15 in Salt Lake City, UT, Garrity has assembled an expert speaker panel that includes Linda Daugherty, deputy associate administrator for Policy and Programs, Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA); Chris A. Paul, shareholder, Industry Group Leader, McAfee & Taft; and John R. Clayton, partner, Jackson Walker L.L.P.

In anticipation of this year’s “Corrosion and Punishment” session, NACE asked the panelists a series of questions to learn about the latest in pipeline safety regulations, the monetary and criminal consequences of noncompliance, and how the pipeline industry is doing overall.Garrity, Daugherty, and Paul provided the following comments.

Q: How would you describe the pipeline industry’s overall safety record?

Garrity: Given the size of our pipeline infrastructure, the industry has an excellent safety record. Having said that, even one incident that places the public safety, property, and the environment at risk is one too many.

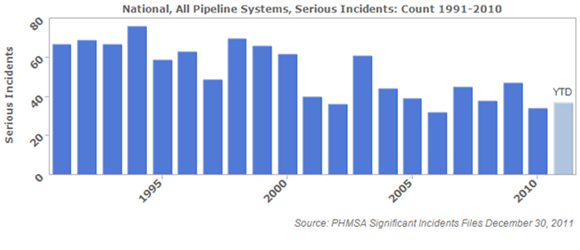

Daugherty: Overall, pipeline safety is continuing to improve. When looking at the long-term trends, incidents involving death or major injury have been going down since the mid-1980s (Figure 1). However, recent incidents such as those in San Bruno, CA; Allentown, PA; Marshall, MI; and other places across the country are a reminder that we still have much work to do.

Paul: By any measure, pipelines are the safest means for transportation of liquids and gas. Recent challenges such as the obstacles to Keystone XL construction are disturbing because politics and junk science combined with deliberate ignorance of facts are driving decisions that harm the economy and ultimately slow safety efforts.

Q: How has heightened regulatory oversight on pipeline safety and integrity impacted the industry?

Daugherty: Reasonable and effective regulations that are consistently applied to all companies improve safety and support a successful industry. Considering the sheer volume of flammable natural gas and hazardous liquids that are transported through our neighborhoods and across the country, it is critical that everyone is held accountable to safety standards. PHMSA regulations contain both prescriptive minimum standards and performance-based integrity management requirements for pipelines. These requirements intensify an operator’s obligation to conduct more safety-related activities along their systems to provide increased protection for high-consequence areas like high population centers.

Paul: First, any implication that heightened regulatory oversight means that PHMSA or its predecessors were soft on the pipeline industry is flat wrong. The Department of Transportation and state pipeline regulatory agencies have consistently had effective programs for inspection, enforcement, expectations, and accountability. This is one reason why pipelines have been and remain so safe. Another reason is that the agencies and the industry have the same goal—safe and reliable transportation—simply, keep the product in the pipe.

What has changed is that the ante has been raised with the prospect of higher penalties and regulators requiring more proof of preparation and performance. For example, corrosion-control personnel are expected to do their jobs with precision and complete and accurate documentation; management is expected to provide adequate resources to facilitate corrosion-control activities; vendors are expected to deliver on their equipment and performance promises; and companies are expected to conduct due diligence to ensure that everything is being done to meet regulatory and industry standards, and ultimately protect the public.

The agencies are providing another level of oversight to determine, before and after incidents, if necessary and required activities are being done and done right. The industry has responded by improving already effective systems. The concern is that — when provided a bigger hammer — regulators will continue to enforce appropriately. The industry has been blessed with regulators who not only effectively address public concerns and real safety issues, but also understand operations, safety, and the business overall, and usually apply enforcement tools that improve performance, rather than run up statistics on fines and penalties. If the pattern of effective inspection and enforcement continues, performance will continue to improve.

Garrity: In my view, the regulations have always helped to maintain a heightened awareness of the need for risk assessment, integrity management, and corrosion-control practices in the pipeline industry. This has a direct and measurable impact on improving safety and decreasing the number of incidents. By contrast, the water and wastewater industry and bridge infrastructure are not regulated to any great degree and the magnitude of problems and deficiencies is astonishing. It is estimated that as many as 100,000 bridges in the United States may be structurally deficient. Corrosion and material degradation play a significant role in bridge component deterioration.

Q: From a pipeline operator’s perspective, who in the organization is typically responsible for ensuring pipeline integrity and safety? Is this role changing? If so, how?

Paul: For the clients we work with, the answer is everyone. The culture of ownership issues and taking responsibility runs deep in most pipeline companies. The role is not changing, but ultimate accountability has shifted somewhat over the last few decades, and this shift is accelerating. For example, while the corrosion-control personnel have specific responsibilities and thus certain legal exposures, these responsibilities are shared with management personnel who, because of such policies as the Responsible Corporate Officer Doctrine, cannot delegate away accountability for compliance with various laws and regulations.

Garrity: The responsibility for pipeline integrity management has historically fallen on the shoulders of the integrity manager; however, recent heightened awareness hasextended the role to all company stakeholders in the integrity process and extends to the senior executives of the operating companies. The changing culture has placed integrity in the realm of corporate safety where all employees are responsible for safe work practices.

Q: Who is responsible for ensuring pipeline integrity and safety from a regulator’s viewpoint?

Daugherty: Although the primary responsibility for a safe pipeline rests with the company that operates it, all stakeholders have a role in ensuring that pipelines do not pose a threat to safety. Individuals and excavating companies bear a responsibility to use the “811—Call Before You Dig” programs to prevent damage to pipelines. Federal and state regulators must develop sound regulations and provide oversight to ensure compliance. The public, workers, industry, and others should make sure their voices are heard during regulatory development.

Finally, legislators must develop laws that provide authority and direction to safety efforts. The Pipeline Safety, Regulatory Certainty, and Job Creation Act of 2011, recently signed into law by President Obama, sent a clear message about the importance of the safety of our nation’s pipeline infrastructure.

Q: What can a pipeline operator do to reduce the likelihood of pipeline incidents?

Paul: The obvious and first step needs to be to continue working to prevent third-party damage. For prevention of other incidents we try to focus clients on three of the critical factors in any solid compliance and performance program: recordkeeping (knowledge of the system, integration of data, and sharing of information); training (teaching, learning, and transferring of both technical and institutional knowledge); and audits (make sure things are working and make changes to improve performance).

The enemies of effective performance are complacency and a lack of urgency, compounded by the moving target of new and changing regulations that drain resources and sometimes destroy focus. A moratorium on new regulations for a few years would be useful since the resources needed to implement changes are several orders of magnitude beyond those necessary to simply say what should be done. And the resource constraint is generally not financial—the constraint is in finding the right people with the right education and experience to conduct and manage work.

Daugherty: Threats such as corrosion, outside force damage, material defects, and others can all seriously diminish the integrity of an operator’s pipeline system. Operators need to continuously evaluate their systems to understand if these threats can impact their ability to operate safely. In addition, pipeline operators should think about other issues that could threaten pipeline safety, such as incomplete operational records and the adequacy of personnel training and qualification. Fostering a safety-first culture at all levels can lead to unexpected benefits and performance improvement.

Garrity: Pipeline incident reduction can be achievedby following these procedures:

1. Conduct due diligence audits of your processes.

2. Assess the potential for unique conditions that may impact safety.

3. Ensure that integrity and risk personnel are properly trained.

4. Ensure that you know your system and its complexities and unique threats that may exist.

5. Develop standardized approaches to investigating failures and releases, for example:

- Ensure timely and appropriate reporting.

- Preserve the integrity of forensic material and data.

- Qualify outside laboratories that can be used to develop reliable and defensible results.

- Designate a corporate spokesperson to ensure that information is not improperly communicated or misrepresented.

- Engage the regulatory authorities.

Q: What should a pipeline operator do if an incident does occur?

Daugherty: Every operator should have an emergency plan that clearly identifies what to do if an incident occurs. In accordance with regulatory guidelines, operators should communicate and pre-plan responses with emergency responders before an incident occurs. If an operator has an indication that something unusual is occurring on its pipeline system, it should contact 911 or emergency officials who may be able to provide information gained from other sources. In addition to calling 911, operators are required to contact the appropriate federal, state, and local response organizations immediately following the discovery of an incident.

Garrity: Emergency plans need to stipulate procedures for failure investigation, corrective action, and return to service. It is critical to develop standardized approaches to investigating failures and releases, including timely and appropriate reporting, preservation of forensic material and data, and use of outside laboratories with the proven ability to provide reliable and defensible results. As I mentioned earlier, a knowledgeable corporate spokesperson should be designated to communicate accurate information to regulatory authorities and the general public. Finally, following a pipeline failure, it is necessary to inspect other areas along the system with similar characteristics and perform a risk assessment.

Paul: The best plans are those practiced through exercises and that,for real events, call for initial over-resourcing until the scale of the event is clearly defined. From a legal standpoint, we stress that protecting a company’s reputation for credibility is key to effectively managing an incident. We try to avoid speculation, understating impacts, or allowing issues to be overstated. Part of the operator’s job is to handle incidents and,despite media labels, most incidents are not crises or catastrophes.

Also, part of preparation involves how to deal with the focus that will be put on safety and integrity programs during, and for long after, an incident occurs. Obviously, being in a position to demonstrate that steps were taken to avoid the incident in the first place is critical. For example, records of corrosion management programs will be scrutinized, underscoring that these programs are part of the larger integrity and safety programs.

Q: What are some practices that should be implemented by a pipeline operator to ensure its pipeline safety and integrity programs and incident response plans can stand up to scrutiny by regulators and the public in the event of an incident?

Paul: Again, train, document, and check. Ensure that personnel are qualified—Operator Qualification is one example, as well as Incident Command training, but other training is critical, even if not required specifically by regulations. Documentation, whether plans, policies, procedures, or records of ongoing activities, needs to be accurate and available on a timely basis. Check means that the operator has programs in place to test itself(sometimes through an audit) to make sure its programs and plans meet compliance requirements and are in line with industry standards.Finally, operators cannot discount the benefits of learning from others through, for example, benchmarking programs or sharing lessons at industry- or agency-sponsored forums, and then applying this knowledge to improve the effectiveness of safety and integrity programs.

Daugherty: Pipeline operators can take a number of actions to enhance the safety of their operations and response capabilities. These activities can include fostering a safety-first culture, knowing and understanding safety requirements, identifying and addressing threats to integrity, and continuously communicating with emergency responders to be prepared if an incident occurs. It is also important for pipeline operators to help spread the word about “811—Call Before You Dig” programs and to be good neighbors by communicating with local officials and landowners.

Q: Is there anything else you would like to add?

Paul: Even with extraordinary efforts and the best technology, accidents will happen. Companies in this industry are made up of people who often live in and alwaystruly care for the communities in which they operate. When an accident occurs, the concern is for those impacted, and operators really try to make things better. In my years of working with pipelines, I have never seen a client put fear of a legal exposure or expense ahead of a safety or integrity issue. I think the regulators have observed this as well, and the result is reflected in an effective form of oversight and very safe, efficient, and reliable systems.

About the Panelists

Kevin C. Garrity issenior vice president of engineering, Special Projects and Consulting for Quanta Services Company’s Mears Group, Inc., an international engineering and construction company headquartered in Rosebush, MI. He ispresidentof NACE International for the 2012-2013 term. An active member of NACE since 1982, Garrityhas served in several capacities among both administrative and technical committees of NACE. He served three independent terms on the NACE Board of Directors—as Public Affairs Committee chair/ex officio director, director at large, and Member Activities Committee director. In addition to his active association service via committee work, Garrity has served in the various Area and Section arms of NACE. He has delivered numerous oral presentations as well as published a lengthy list of articles, papers, and education courses. Honors and awards include NACE CORROSION 2006 Plenary Lecturer, 2010 NACE Distinguished Service Award, and the Appalachian Underground Corrosion Short Course Colonel George C. Cox Award for Outstanding Contributions to Underground Corrosion.

Garrity holds a B.S. degree in electrical engineering from the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn (New York University) and holds professional engineering registrations in Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Louisiana, Kansas and Ohio. Garrity is a NACE certified Cathodic Protection Specialist and is a NACE CP1, CP2, and CP2—Marine instructor.

Linda Daugherty, a chemical engineer, brings more than 23 years of engineering and enforcement experience to her work with the engineering and administrative professionals in PHMSA.She started her pipeline safety career with a hazardous liquid pipeline company in the Midwest and joined PHMSA’s Office of Pipeline Safety (OPS) in 1991 as a pipeline inspector/investigator. She later moved to Washington and for nine years managed the OPS national enforcement program and served as the HQ Emergency Coordinator for pipeline accidents and national emergencies.

In 2003, Daugherty became the Director of the PHMSA’s Southern Region in Atlanta and in 2010 was appointed as the Deputy Associate Administrator for Policy and Programs. She helps PHMSA engage the public’s trust on pipeline safety matters through strategic action, effective coalitions, and open communication with all stakeholders.

Chris A. Paul has extensive experience with legal issues involving products, crude oil, and natural gas liquid pipelines, including system acquisitions and divestitures, capacity leasing, real estate and right-of-way issues, feedstock and product quality issues, operating agreements and contracting, SCADA issues, security and public awareness programs, DOT, TSA, and EHS compliance, emergency response, and litigation activities. He is admitted to the bars of the states of Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Arkansas, and Kansas;the United States Supreme Court; and various United States district courts. He is an instructor for the Oklahoma State University Environmental Management Certificate Program and a member of the Transportation Lawyers Association.

Paul earned his J.D. from the Marshall-Wythe School of Law at the College of William and Mary in 1983, and his B.A. in international studies and history from Dickinson College in 1980. Prior to entering private law practice in 1996, he was in-house counsel for Sun Company and Sun Pipe Line Company, and served as Environmental Department Manager, Sun Company, Tulsa Refinery. He served on active duty as a U.S. Army JAGC lawyer with the Seventh Infantry Division, and as a Special Assistant United States Attorney for the Northern District of California.

Comments