January 2013, Vol. 240 No. 1

Features

Jobs In A Ripple-Out Economy Come From Oil, Gas, Coal, And Then The Cloud

You can’t escape the irony. Ohio is doing better. Jobs are coming back and they are energy jobs.

No, not from wind, battery and electric cars, but from oil and gas. Ohio is already well along its way to a jobs recovery in large measure from a hydrocarbon boom.

A portentous study early last year itemized the economic impact of developing oil and gas from the Utica Shale formation that’s located several thousand feet below Ohio’s farmlands. The estimates: just for Ohio, by 2015, we should see 200,000 jobs in this sector, some $12 billion in wage growth and a rise of $22 billion in economic output.

Talk about the proverbial “gift horse.” That’s great for Ohio. What about the rest of the country?

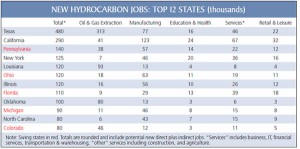

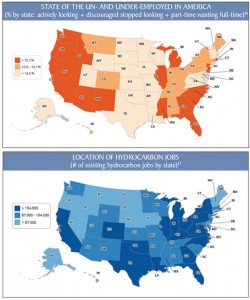

Of the 12 states that stand to gain the most from a hydrocarbon boom, five are political “swing states” where over a half-million jobs would be generated. In addition to Ohio, look to Pennsylvania, Florida, Michigan, and Colorado. Or measured another way: the number of new workers that will come from hydrocarbon expansion equals one-fifth to three-fourths of all those people counted as unemployed or underemployed in at least 20 states, including those in Wisconsin, Colorado, Iowa, Ohio and Pennsylvania.

The nation stands to gain more than 4 million jobs in the near future from expanding hydrocarbon production – oil, natural gas and coal. More than 8 million Americans lost jobs between February 2008 and 2010. Since then, through August 2012, barely more than 4 million jobs have been created. We need a lot more jobs, and quickly. Why not embrace the hydrocarbon boom that began, quietly, unbidden, and even accelerate it? (To drill deeper on the facts that make this possible, see Unleashing the North American Energy Colossus, and from the U.S. Chamber we welcome the additional perspective of a new report with a full-throated embrace of this paradigm.)

The hydrocarbon boom is galloping along despite regulatory headwinds bemoaned by everyone on the front lines, and without specific federal incentives. America’s oil output has risen more than anywhere else in the world, with domestic production reversing a four-decade decline. There’s so much oil that we’re shipping it around the country by truck and rail for goodness sake, awaiting new more cost-effective pipelines.

Natural gas production has soared so much that there’s a glut, and a back-up in applications to export it. And coal exports are soaring to meet world demand, also in spite of bottlenecks in getting export facilities expanded. This boom can be squelched by oppressive regulation, or it can embraced, with attendant job acceleration in dozens of states.

And while there are a lot of old-fashioned hard-hat jobs in this boom, that’s not what this is all about. For every direct hydrocarbon job created in the field, another six jobs are created in the economy from manufacturing and education, to health care and information services. The economic boom leads to enhanced royalties and taxes that help to fund social programs, research and education. It’s how a ripple-out economy works.

Employment from expanded domestic oil, gas and coal output– and, importantly, exports –is associated with more than $2 trillion in total economic benefits to our society from all the hydrocarbon production. We don’t need stimulus funds to create such jobs, so taxpayers are off the hook. Hydrocarbon employment creates a net societal benefit of $500,000 per job. The broad economic benefits show up not just in jobs and incomes, but also in huge reductions in imports and our trade deficit, as well as reductions in both state and federal debt. All we need to do is ensure that regulations meet the intent of the rules and are not punitive or obfuscatory.

Where did the boom come from? In a word: technology. Not federal programs. The quantity of energy you can find in the first place, and then extract, is entirely a function of technology. (Something my colleague and I forecast in our 2005 book, The Bottomless Well.) Most of the punditocracy has been preoccupied with how technology enables energy alternatives to oil, gas, or coal. But they’ve missed how new technology has quietly unleashed the ‘old’ stuff.

It is by now obvious that government can’t buy its way out of the jobs deficit by playing investor, spending tens of billions on favored industries. Little need be said about the roster of embarrassing examples from Solyndra to A123. But it really wouldn’t matter what the industries are, the nation can’t afford the price tag associated with buying jobs.

It should be unsurprising that the hydrocarbon industries unleash jobs at this scale. More than 80% of the U.S. and world’s energy needs are met with hydrocarbons. About 10 million Americans are already employed directly and indirectly in businesses associated with oil, natural gas and coal production. These jobs are widely distributed across the nation: 16 states have more than 150,000 people employed by hydrocarbon-related activities.

Obviously, over the longer term, hydrocarbons cannot be the only answer to the country’s staggering jobs deficit. The majority of people work in businesses that consume energy, not produce it. So it is with agriculture and manufacturing, and so it should be.

It will be innovation more broadly, and new technologies across all sectors of our economy,that will create long-term expansion for the economy and a new great cycle of job growth. (See The Next Great Growth Cycle.) Manufacturing is coming back, and is being revitalized by advancing technology from the full infusion of information technology to the seeming magic of emerging 3D printing.

Then there’s the emergence of the Cloud, the next phase of the information revolution driving job growth in transportation, manufacturing, construction, education, retail and healthcare. A recent study from tech analysts at IDC forecasts a million American jobs within a few years from Cloud trends, spread across every discipline. But forecasters almost certainly underestimate the jobs and productivity growth from the next great tech cycle. Wind the clock back to 1979, and no one, not a single pundit, policy wonk, or economist, forecast the economic boom that came from the last such cycle.

But given the depth of the employment crisis, emerging technologies cannot revitalize America fast enough. We can prime the pump though, and go a long way towards reversing the long stagnation in income growth. We can do it with hydrocarbons.

Policies

Developing and implementing policies that will not just continue but accelerate the boom in domestic hydrocarbon production will enable us to rapidly realize the economic and jobs benefits outlined above.

Recent history shows that these jobs can be created quickly. Both production and employment have grown from marginal or near zero in certain parts of North Dakota, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, for example, to become major forces in only a few years. The same could happen in many states, not just Texas, Oklahoma, and Colorado, but also in California and New York.

However, the remarkable gains in production are not guaranteed to continue. They are at risk if new restrictions are imposed on the industry, from delays in approval of LNG exports, to opposition to expanding ports for coal export, to opposition to pipelines and refineries, and to the threat of redundant federal regulations on the technology of hydraulic fracturing.

Conversely, more jobs could come sooner under policies favorable to development which ameliorate, suspend, or remove regulations that have created either unintended or intended impediments to domestic production.

Jim Clifton, the Gallup Organization’s Chairman put it well in his new book, The Coming Job Wars: “Jobs are the heart and soul of a nation, the thing that sustains everyone. … But almost nobody knows where or how jobs are created, especially those who think they know how to create jobs – the government, academics, experts from institutions of all types. Those people are usually the most wrong about job creation. They tend to dig in the wrong places.”

Well, in Ohio, Pennsylvania, North Dakota, Texas – and yes, maybe even California and New York before long — that digging has started.

P.S. Want to make investment bets on this trend? As I’ve suggested before, you can follow the fortunes of the major hydrocarbon tech suppliers like Baker Hughes [NYSE:BHI], Schlumberger [NYSE:SLB], and Halliburton [NYSE:HAL]. Also see my earlier column on the Ohio boom, and where Bill Gates is making his bets in the oil fields.

The Author

Mark P. Mills is founder and CEO of the Digital Power Group, a tech-centric capital advisory group. He was formerly the co-founder and chief tech strategist for Digital Power Capital, a boutique venture fund. He co-founded and served as Chairman and CTO of ICx Technologies helping take it public in a 2007 IPO. Mark is a member of the Advisory Council of the McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science at Northwestern University, and serves on the Board of Directors of the Marshall Institute.

He writes the Energy Intelligence column for Forbes and is co-author with Peter Huber of the book, “The Bottomless Well” (Basic Books 2005). He was a technology adviser for Banc of America Securities, and a co-author of a successful energy-tech investment newsletter, the Huber-Mills Digital Power Report, published by Forbes and the Gilder Group. He served in the White House Science Office under President Reagan. Early in his career he was an experimental physicist and development engineer in the fields of integrated circuits and microprocessors and worked at Bell Northern Research (NORTEL) in fiber optics, defense and solid-state devices, fields in which he holds several patents. He holds a degree in physics from Queen’s University, Canada.

Comments