December 2021, Vol. 248, No. 12

Features

Produced Water: Path to Economic, Environmental Gains

By Richard Nemec, Contributing Editor

Once a unit of Occidental Petroleum Corp. that went through Chapter 11 bankruptcy since it was spun off in 2014, California Resources Corp. (CRC) is California’s largest oil and natural gas producer. CRC is working to significantly increase the volume of produced water reused in its operations involving steam flooding for enhanced oil recovery (EOR).

In mid-2021, the medium-sized independent found itself more than halfway toward a goal of using 30% more produced water compared to a 2013 baseline. CRC serves drought-plagued California by reusing, recycling and reclaiming water from the state’s extensive oil and gas formations that would not otherwise be available, aiding both agriculture and industry.

A net water supplier to the state, CRC applies two annual sustainability metrics to its water use efforts. A state law mandated 20% reduction in water use statewide in 2020 and sustainability goals to conserve potable water and to reuse, recycle and reclaim other water supplies by 2030, which would include the water produced through oil and gas operations.

“We directly reuse or recycle 78% of our produced water in our improved and enhanced recovery operations, typically in a closed-loop system by reinjecting it into the same oil and gas reservoirs from which it came,” said CRC spokesperson Richard Venn.

Recycled produced water is CRC’s primary water source for its ongoing operations, and Venn noted that the company has invested in “significant” water recycling and treatment facilities. CRC’s operations are closely monitored to ensure that its use of water does not affect the accessibility and volumes of high-quality water for domestic uses in cities, towns and agriculture (ranches and farms).

California state procedures “encourage,” but don’t mandate, alternative water sources for oil and gas operations. However, to obtain a well stimulation or hydraulic fracturing (fracking) permit, operators must work with the California Geologic Energy Management (CalGEM) division of the Conservation Department “to determine the quantity of water to be used and the source and supplier.” The state considers recycled and saline water to be preferred sources for well stimulation treatment.

CalGEM requires each operator to conduct feasibility studies to determine if recycled or alternative water sources, including produced water, “may effectively be used.” Under state law (Senate Bill 1281), oil and gas producers must submit monthly and quarterly reports on sources and distribution of the water they use. Flowback water and saline groundwater are two other alternatives that operators must consider before gaining a well stimulation permit.

CRC has reduced its fresh water use in upstream operations to a third of its total use with more than half (56%) used to generate electricity at its Elk Hills and Long Beach operations. The rest is used in its farming operations on its company-owned acreage.

“During the height of the 2016 drought, we reduced our fresh water from a local district supplier by 43%,” Venn said. “In 2019, we supplied more than 5.35 billion gallons of treated, reclaimed produced water for agricultural use, or 12% of the volume of produced water our operations generated during the same year that we reclaimed nearly all of the produced water from our steam flood operation in the Kern Front field.”

For more than a decade, federal water officials have been touting produced water for drought-prone areas in the West. “Produced water is a waste byproduct of the oil and gas industry; however, with appropriate treatment and application to beneficial use, produced water can serve as a new water supply in the western United States,” researchers in the Department of Interior wrote in 2011.

Over the years, the Bureau of Reclamation Technical Service Center has gathered data from publicly available sources to describe the water quality characteristics of produced water, assessing water quality in terms of geographic location and water quality criteria of potential beneficial uses, identifying appropriate treatment technologies for produced water and describing practical beneficial uses of produced water.

Mostly groundwater naturally occurring deep in oil and gas reservoirs, produced water also can include water previously injected into the formation during well treatment or secondary recovery to increase production, along with residuals of any chemicals added during the oil and gas production processes. Flowback water is a third source of produced water as the water returned to the surface after hydraulic fracturing.

According to the Groundwater Protection Council’s 2019 report on produced water, it is classified as an “exempt” oil and gas waste stream, meaning it is not subject to hazardous waste provisions in the federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act.

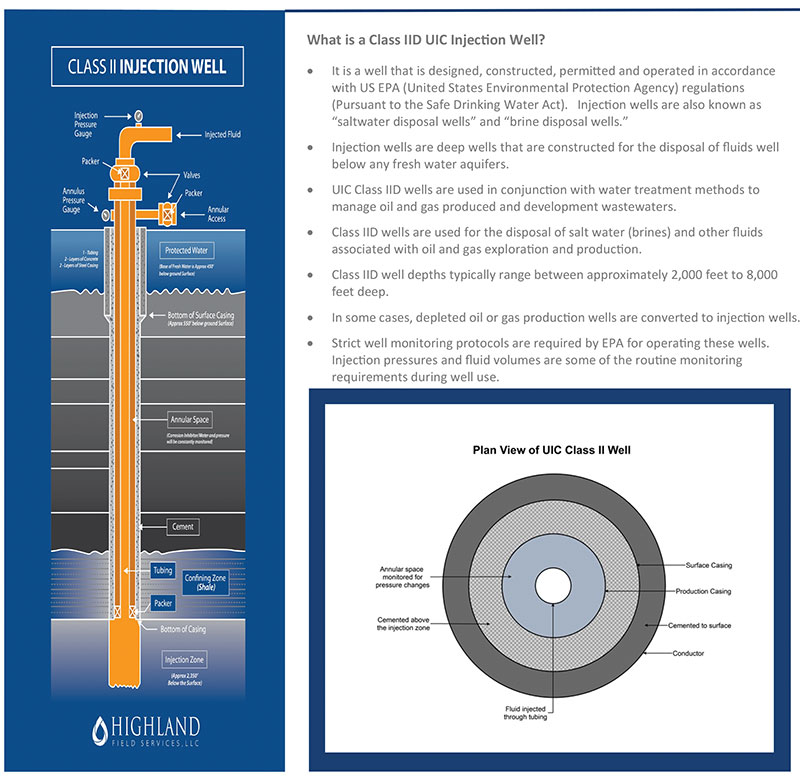

The report profiled the seven major U.S. oil and gas basins/regions: Permian, Appalachian, Bakken, Niobrara/Denver-Julesburg, Oklahoma, Haynesville and Eagle Ford. The management of produced water is subject to two federal permitting programs – the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) program and the Underground Injection Control (UIC) program, both of which are primarily regulated by states.

Produced water varies widely in quality. Most of it is high in saline, containing a mix of mineral salts, organic compounds, hydrocarbons, organic acids, waxes and oils, along with inorganic metals, other inorganic constituents, naturally occurring radioactive material, chemical additives and other constituents and byproducts, the council report noted.

The council document also said as fresh water sources become more restricted, “the ability to use produced water to offset freshwater demands both inside and outside of oil and gas operations will offer opportunities and challenges.

“Increasing produced water reuse holds promise for making available a substantial volume of water that could potentially offset, or supplement, fresh water demands in some areas. Reuse also can be beneficial to oil and gas producers as an alternative to disposal in underground injection control [UIC] wells, which can be costly, locally unavailable or subject to volume restrictions.”

Nationally, there is a lot of ongoing research looking to lower the cost of treating and reusing produced water, such as at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). DOE is funding several new research and development (R&D) projects aimed at reducing the cost of treating and reusing produced water; the overall goal being “to transform produced water from a waste to a resource,” according to the federal agency. A typical multistage fracking of a horizontal well uses an average of 12 million gallons of water.

DOE has previously invested approximately $100 million into produced water projects and continues to collaborate with industry, universities, state governments, other federal agencies and non-governmental organizations.

“Produced water R&D is important because the development of our nation’s unconventional oil and natural gas resources is directly connected with the use of water,” DOE officials noted. “Water is used to drill wells and fracture oil- or gas-bearing formations. Water is also an important co-product that is brought to the surface with the oil and natural gas, resulting in produced water.”

In the robust Permian Basin, Occidental Petroleum (Oxy) officials tout their mid-major operations “as a leader among our peers, produced water consortiums, and environmental groups regarding water stewardship and technology advancements.”

“We consistently make operational improvements in addition to working toward our net-zero goals,” Oxy CEO Vicki Hollub noted during a first quarter of 2021 earnings conference call. “In the first quarter, we started a water recycling facility in the Midland Basin and began utilizing recycled water in our South Curtis Ranch development. In partnership with an industry-leading water midstream company, we increased our water recycling efforts and lowered costs. Recycling water has been a large focus of ours in New Mexico for several years, and we are pleased to have been able to expand this effort into Texas.”

(In late 2021, the Texas facility had already recycled approximately 3 million barrels of water for Oxy’s hydraulic fracturing operations with zero disposal during this initial period of operation.)

In 2015, as part of its commitment to environmental stewardship, Oxy significantly ramped up produced water recycling in the Permian Basin in New Mexico, building six dedicated produced water recycling facilities. Four years later, Oxy’s use of recycled water from the facilities avoided 25 million barrels of fresh and/or brackish water from being used, according to company spokesperson Jennifer Brice.

“This year, the construction of a new state-of-the-art produced water recycle facility was completed through a collaborative design with a midstream company, Select Energy Services, just north of Midland, Texas,” Brice said. The site is serving multiple operators providing water balancing supply synergies beyond the needs of a single operator, she noted.

Brice also pointed out that in addition to these produced water recycling facilities, Oxy has “actively supported” the State of New Mexico’s produced water desalination research efforts, providing facilities for field testing via the New Mexico Produced Water Research Consortium – a joint project between the New Mexico Environment Department and New Mexico State University.

In New Mexico, a 2019 law and subsequent new regulations last year finalized changes to its produced water regulations on the oil and gas industry after months of adjustments and debate among state regulator, environmentalists and oil and gas industry leaders. The state Oil Conservation Commission unanimously approved the changes late last year without discussion following two days of testimony from environmental groups and industry leaders.

An arm of the New Mexico Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department, the commission regulates the management of produced water within the industry while the New Mexico Environment Department oversees any future uses of the water outside of the oil and gas industry in sectors such as agriculture.

“We plan to engage in similar work and studies envisioned with the newly forming Texas Tech Produced Water Consortium,” Brice said. Through these organizations, she maintains that Oxy can successfully help advance produced water education and public-private partnerships among universities, energy producers, regulatory agencies and local governments. From Oxy’s perspective, the goal is to seek out and evaluate cost-effective technologies that will provide beneficial use of produced water and help sustain freshwater resources in the Permian Basin.

Re-use Sought

To the north in the Bakken Shale play in North Dakota, a strong desire for more reuse of produced water was running headlong into some of the side effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Progress stalled in the fall because of supply chain problems globally due to the pandemic-induced economic slowdown worldwide, according to Lynn Helms, director of the state Office of Department of Mineral Resources.

“Unfortunately, there hasn’t been any progress,” Helms reported on a mid-October webinar releasing increased oil and gas production numbers for the Bakken. “I talked recently to a service provider that is interested in using more produced water, and we have a meeting with a second service provider, but because of the supply chain problems they have not been able to get the monitoring equipment they need, so we’re still on hold in terms of testing its first systems.”

With the winter months approaching, Helms indicates it is likely moving ahead with more produced water use and will have to wait for the spring thaw. If the supply chains clear up in October, however, the needed monitoring equipment could be placed in service still in 2021, Helms said. “We want to be very cautious because of the salinity of our produced water to make sure all the monitoring systems are in place to do this safely,” he said.

In the plentiful gas-producing unconventional Appalachian basin covering parts of Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia, the importance of water management in various shale plays has emerged in recent years, according to a variety of stakeholders and commentators. It is increasingly viewed as a critical component of shale oil and gas development. While important in places like the Permian and Oklahoma, at least one Appalachian operator identified early on the challenges that large amounts of produced water could present to unconventional production, and it put a plan in place to manage water challenges.

“Water reuse and recycling was pioneered in the Marcellus Shale play more than a decade ago and is common practice among the state’s natural gas producers,” said David Callahan, president of the Marcellus Shale Coalition, noting that currently 93% of fluids are recycled and reused in Pennsylvania. “This is a primary example of how oil and gas operators drive innovative solutions that protect and conserve our shared environment. We’re proud this technology began in the Marcellus and is being adopted across the country, as recycling wastewater is an economic and environmental winner.”

Callahan predicts that water management practices will continue to be key to sustainability efforts as companies work to develop energy “in the most environmentally responsible manner.”

Southwestern Energy Corp. is one of many Marcellus operators with a robust produced water recycling program, reusing approximately 99% of their water in northeastern Pennsylvania and 52% in the Southwest region. Southwestern officials said the company has been “freshwater neutral” over the past four years, while being equally committed to responsible produced water management and the protection of groundwater.

According to Southwestern operators, hydraulic fracturing requires more water than any other aspect of their operations because it is used as the base for fracturing fluids and to mix well cement and drilling mud, pressure-test pipelines, cool compressor stations and conduct other minor operational functions.

“Our water needs vary basin-to-basin, and even pad-to-pad due to differences in reservoir geology, well depth, lateral length and other operational factors,” the officials noted, adding that the company’s overall water use increased in 2019 from 2018.

Average water use per well also increased in both northeast and southwest Appalachia, primarily attributable to increased lateral lengths and evolving fracturing fluid designs that require more water per well. It averaged 340,000 barrels per well (b/well) in the northeast and 381,000 b/well in the southwest.

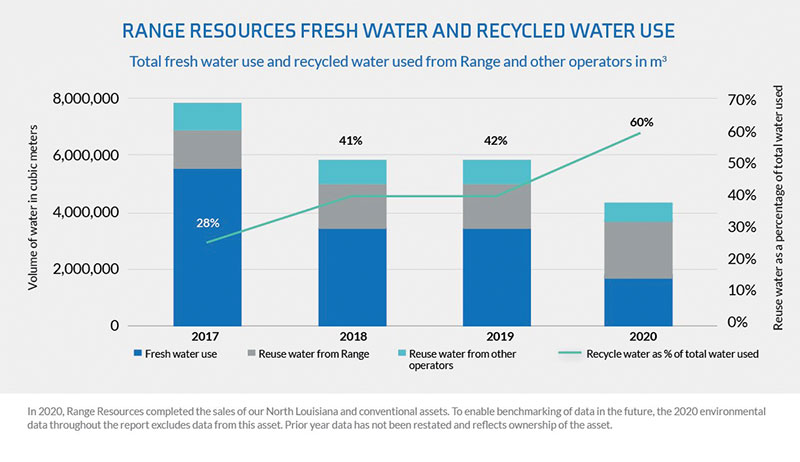

In 2004 a leading Appalachian producer, Range Resources Corp., drilled the first discovery well in the Marcellus Shale with the Renz #1 well in Washington County, Pennsylvania, according to Tony Gaudlip, Range’s vice president of Operations Planning. Gaudlip said that in 2009 Range pioneered reuse of produced water and became the first operator to achieve 100% use of it as a water source.

“As the play got bigger and people recognized how big it could be, we recognized that water was going to be an issue, simply because of the magnitude,” said Gaudlip, adding that Range now uses almost 100% of flowback, produced and containment water for its operations. They also recycle other operators’ water in the region to reduce freshwater usage even more.

In 2020, Range recycled more than 5 million bbls of water from other operators in the area in addition to the 99.18% of its own more than 10.4 million barrels of water. “We reused 795,553 barrels of flowback and produced water from third-party operators, with total reused water amounting to 147% of Range-generated flowback and produced water in Pennsylvania,” a Range spokesperson said. “We’ve saved $10 million per year in 2018 and 2019, for a combined savings of $22.1 million as a result of our water recycling program.”

Constant Reevalutation

Range constantly reevaluates its water management operations and over the years it has identified more opportunities for efficiencies, both in terms of cost and operations. It has eliminated redundant, multiple moves of reused water supplies, company officials point out.

In-house logistics and supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems track each barrel of water running throughout the company’s operations along with tank levels and where water is needed for a fracturing job. Eventually, the company simply delivered the flowback water directly to the next well site.

While recycling all of its produced water, Range still must source additional water for its fracturing jobs. In Appalachia that means using the nearby Ohio River, from which it can get that water to its fracking sites via an underground water pipeline network. Gaudlip maintains that the amount of water drawn from the Ohio is “minimal” to the river’s flow rate.

A report by the American Geosciences Institute observed, “In the Bakken only about 5% of the wells drilled in 2014 used produced water in their fracturing fluid. This is partly due to state’s [then-in place] regulations that prohibited storage of salty produced water in open-air pits and partly because the extreme salinity of produced water in this area makes treatment and reuse difficult and expensive,” according to the Groundwater Council’s report.

In their decade-old white paper, “Oil and Gas Produced Water Management and Beneficial Uses in the Western United States,” Bureau of Reclamation researchers note that the quality of produced water “varies significantly” based on geographical location, the type of hydrocarbon produced, and the geochemistry of the producing formation.

“In general, the total dissolved solids concentration can range from 100 milligrams per liter (mg/L) to over 400,000 mg/L,” they said. Separately, Groundwater Council researchers found that about 45% of the U.S. produced water was used in oil and gas enhanced recovery processes and the vast majority of the rest was disposed of in permitted UIC wells.

Silt and particulates, sodium, bicarbonate and chloride are the most commonly occurring inorganic constituents in produced water. Benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene (BTEX) compounds are the most commonly occurring organic contaminants in produced water, the federal reclamation agency noted.

“The types of contaminants found in produced water and their concentrations have a large impact on the most appropriate type of beneficial use and the degree and cost of treatment required. Many different types of technologies can be used to treat produced water; however, the types of constituents removed by each technology and the degree of removal must be considered to identify potential treatment technologies for a given application,” according to the reclamation researchers.

For the oil and gas industry in the future, three areas still present challenges and unanswered questions – the regulatory and legal framework for reuse of produced water, future potential for reuse in the growing unconventional basins, and opportunities and research needs.

Anyone seeking insights into these three areas of concern should study the Groundwater Protection Council’s 2019 report, which addresses an array of issues.

The report includes an assessment of 18 separate produced water programs, an evaluation of state regulations and laws covering produced water by the Louisiana State University law school and a four-phase conceptual research framework for assessing risk in water reuse.

The council report also provides an overview of various treatment technologies that exist or are being currently researched, along with a literature review identifying hundreds of published, peer-reviewed studies and referencing other reports, which may be relevant to assessing produced water reuse or identifying knowledge gaps and current limitations.

For anyone parched for data and ideas on produced water, there is plenty to quench their thirst.

Richard Nemec is P&GJ’s contributing editor based in Los Angeles. He can be reached at rnemec@ca.rr.com

Comments